| Content | Guidance, clarification & links |

| • Normal distribution and bell-shaped curve • Properties of the normal distribution • Diagrammatic representation & 68–95–99.7 rule • Normal probability calculations (technology) • Inverse normal calculations |

• Recognise natural occurrence of normal data • Understand symmetry about mean μ and spread via σ • Approximately 68% within μ ± σ, 95% within μ ± 2σ, 99.7% within μ ± 3σ • Use GDC for probabilities and inverse normal • No need to transform to standardised variable z for exams |

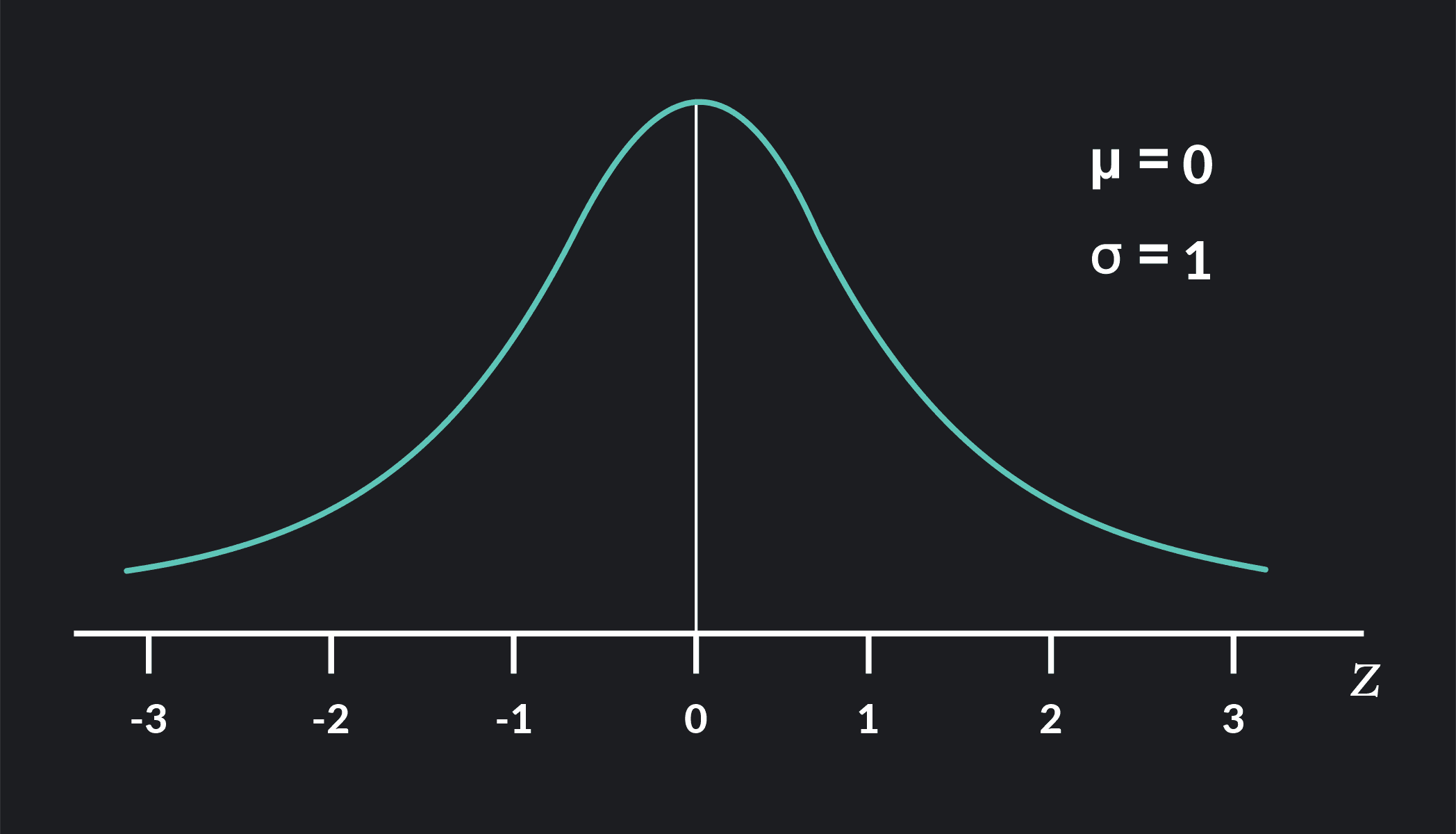

1. The Normal Distribution and Curve

The normal distribution is a continuous probability distribution with a characteristic

bell-shaped curve. A normal random variable X is written as X ~ N(μ, σ), where:

- μ = mean (centre of the distribution)

- σ = standard deviation (measure of spread)

- The curve is perfectly symmetric about x = μ.

- The highest point (peak) of the curve occurs at x = μ.

- Total area under the curve = 1 (represents probability 1).

Unlike discrete distributions (such as binomial), the normal distribution is

continuous. Probability is represented by area under the curve, not by bars.

For a single exact value P(X = a) = 0; we always consider intervals such as P(a < X < b).

Many real-life measurements are approximately normal:

- Human heights and masses within a population

- IQ scores and some psychological test scores

- Measurement errors in experiments

- Natural variation in manufacturing processes

Recognising when the normal model is reasonable allows us to make powerful probability-based predictions.

2. Key Properties & the 68–95–99.7 Rule

Important qualitative properties:

- Shape is bell-shaped and symmetric about μ.

- As x moves far from μ, the curve approaches (but never touches) the x-axis.

- Mean, median and mode are all equal to μ.

For many normal distributions, the following empirical rule holds:

- Approximately 68% of data lies between μ ± σ.

- Approximately 95% lies between μ ± 2σ.

- Approximately 99.7% lies between μ ± 3σ.

These percentages provide a quick way to judge whether a value is “typical” or “unusual”.

Values beyond μ ± 2σ are uncommon; beyond μ ± 3σ are very rare in a normal distribution.

When a question asks whether a data value is “unusual” or “consistent with the model”,

compare it to μ ± 2σ or μ ± 3σ and comment using the 68–95–99.7 rule.

A brief sentence such as “this lies more than 2σ from the mean, so it is unlikely” often earns reasoning marks.

3. Diagrammatic Representation

In exam diagrams:

- Draw a smooth bell-shaped curve over the x-axis.

- Mark the mean μ on the horizontal axis at the centre.

- Optionally mark μ − σ, μ + σ, μ − 2σ, μ + 2σ to show the spread.

- Shade the region corresponding to the probability being asked, e.g. x > a or a < x < b.

Even when the question uses technology, a quick sketch with a shaded region helps you

understand what the GDC output represents and can reveal obvious mistakes (like probabilities > 1 or negative).

https://articles.outlier.org/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fkj4bmrik9d6o%2FUuFO0KrA3JNEZfBsG8bSc%2F9fd6ec46281d7e907820cdd1cb75bff9%2FNormal_Distribution_07.png&w=3840&q=75

4. Normal Probability Calculations (Using Technology)

To work with a normal variable X:

- Define the variable clearly:

“Let X be the height (in cm) of students in a school, X ~ N(170, 8).” - Sketch a quick normal curve marking μ and shading the relevant region.

- Use GDC normal distribution functions to find the area (probability).

Common probability types:

- P(X < a) → lower tail

- P(X > a) = 1 − P(X < a) → upper tail

- P(a < X < b) = P(X < b) − P(X < a)

Example 1 – Tail probability

Suppose X ~ N(100, 15). Find P(X > 130).

- Sketch: mean at 100, shade the right tail beyond 130.

- Use your calculator’s normal CDF function with mean = 100, sd = 15, lower = 130, upper = a large number (e.g. 109).

- Result is a small probability showing such a high value is rare.

- For P(X < a), use lower = −109, upper = a.

- For P(X > a), use lower = a, upper = 109.

- For P(a < X < b), use lower = a, upper = b.

- Always double-check that your shaded sketch matches the bounds you entered.

5. Inverse Normal Calculations

Inverse normal problems ask for a value of X corresponding to a given area (probability).

The mean μ and standard deviation σ are given, and we find x such that:

P(X < x) = p or P(X > x) = p or P(a < X < b) = p.

You do not need to transform to the standardised variable z in IB exams;

use the inverse normal function on your GDC directly with μ and σ.

Example 2 – Percentile

Test scores are normally distributed with mean 60 and standard deviation 8.

Find the score that marks the top 10% of students.

- We want the 90th percentile, since 10% are above and 90% are below.

- So find x such that P(X < x) = 0.90.

- Use inverse normal with area = 0.90, mean = 60, sd = 8 → x ≈ 70.2

- Interpretation: students scoring about 70 or above are in the top 10%.

Clearly state whether the area you enter is left tail or right tail.

If the question gives a right-tail probability (P(X > x) = p), convert to a left-tail area first: P(X < x) = 1 − p.

- Sciences: measurement errors, biological variation, experimental data

- Psychology: distribution of test scores and traits

- Environmental systems: variation in environmental indicators

The normal distribution is a model, not reality. Important questions:

- When is it reasonable to assume data are normal, and who decides?

- What happens if we apply the normal model where it does not hold (e.g. income distributions)?

- How do choices about which data to include or exclude influence the “fit” to a normal curve?

Misuse of the normal model can lead to misleading or dangerous conclusions, especially in medicine and social policy.

The normal distribution was developed through work by De Moivre, Gauss and others, and later used by Quetelet to model

“l’homme moyen” (the average man). This illustrates how mathematical ideas can both describe natural patterns and shape

the way societies think about “normality”.

To succeed in SL 4.9, you should be confident drawing and interpreting normal curves, using technology for normal and inverse normal calculations, and critically evaluating when the normal model is appropriate in context.