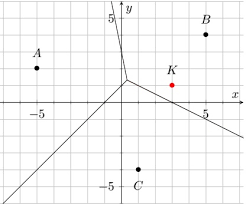

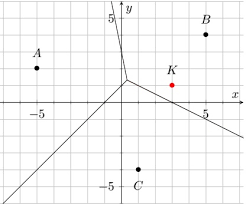

Voronoi diagrams are a way of dividing the plane into regions according to closeness to given points called sites.

Each region contains all points that are closer to one particular site than to any other.

This topic connects coordinate geometry, perpendicular bisectors and a wide range of applications in geography, biology, economics and computer science.

| Term |

Meaning in a Voronoi diagram |

| Site |

A fixed point in the plane, often representing a real object such as a town, weather station or cell tower. |

| Cell (region) |

The set of all points that are closer to a particular site than to any other site. Each site has its own cell. |

| Edge |

A boundary line segment between two cells, consisting of points that are equidistant from two sites.

Algebraically, an edge is part of a perpendicular bisector between two sites. |

| Vertex |

A point where three (or more) edges meet. It is equidistant from three (or more) sites. |

📌 1. Building Voronoi boundaries using perpendicular bisectors

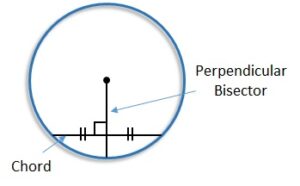

The key geometric idea is that points on the boundary between two sites are equidistant from both.

In coordinate terms, the set of points equidistant from two points A and B lies on the perpendicular bisector of segment A B.

For two sites A(x1, y1) and B(x2, y2):

- The midpoint between A and B gives one point on the boundary.

- The gradient of A B is (y2 − y1) ÷ (x2 − x1).

- The gradient of the perpendicular bisector is the negative reciprocal, −1 ÷ m.

- The equation of the boundary line is then found using the midpoint and this perpendicular gradient.

Voronoi Diagrams: How to Create Stunning Voronoi Diagrams

Example — equation of a Voronoi edge

Two sites are P(2, 1) and Q(8, 5). Find the equation of the boundary between their Voronoi cells.

Midpoint:

M = ((2 + 8) ÷ 2, (1 + 5) ÷ 2) = (10 ÷ 2, 6 ÷ 2) = (5, 3)

Gradient of P Q:

m = (5 − 1) ÷ (8 − 2) = 4 ÷ 6 = 2 ÷ 3

Gradient of perpendicular bisector:

m⊥ = −1 ÷ (2 ÷ 3) = −3 ÷ 2

Equation through M(5, 3):

y − 3 = (−3 ÷ 2) × (x − 5)

This line forms the Voronoi edge between P and Q.

📌 2. Adding a new site to an existing Voronoi diagram

When a new site is added (for example, a new hospital, store or weather station), its cell is formed by drawing boundaries between it and existing sites:

- Take the new site S and each neighbouring site in turn.

- Construct the perpendicular bisector between S and that neighbour; this line is a candidate boundary.

- Only the part of each bisector that is closer to S than to other sites becomes an edge of the new region.

- The final cell may be bounded by several such edges, forming a polygon around S.

Conceptually, you are “carving out” space where S is the nearest site. This models how adding a new facility changes which households are closest to which centre.

📌 3. Nearest neighbour interpolation

Often each site carries a numerical value, for example rainfall at a weather station, pollution level at a sensor or population at a city.

Nearest neighbour interpolation assumes that:

- Every point inside a Voronoi cell takes the same value as that cell’s site.

- There are sudden jumps in value at the boundaries (edges) where the nearest site changes.

This is a simple but powerful way to estimate values across a region using data from a limited number of measurement points.

In practice, it is used in ecology, meteorology and resource management as a first approximation, sometimes improved later by smoother methods.

📌 4. The “toxic waste dump” problem

The “toxic waste dump” problem is a classic application of Voronoi diagrams to optimisation and fairness:

- Several towns (sites) are located on a map.

- A waste disposal site must be placed in a position that is as far as possible from all towns, to minimise risk and political opposition.

- The best location is at a point that maximises the minimum distance to any town.

In a Voronoi diagram, this optimal point lies at a vertex where three edges meet.

At such a point, three towns are equally far away, and all other towns are at least that far or further.

In exam questions you may be given coordinates of vertices and asked to choose the one that provides the greatest minimum distance.

🧮 GDC Use

- Plot the sites as points to visualise the Voronoi cells. Some GDCs or graphing apps support drawing perpendicular bisectors directly.

- Use distance functions to check which site is closest to a given point by computing several distances and comparing them.

- For the “toxic waste dump” problem, store candidate vertex coordinates and evaluate distances to each town using the distance formula on the GDC.

🌍 Real-World Connections

- Urban planning: Assigning each house to its nearest school, hospital or fire station.

- Spread of diseases: Modelling which health centre is likely to serve each area, or which outbreak source is nearest.

- Ecology and meteorology: Dividing a region according to the nearest weather station or sampling site to estimate rainfall, temperature or species density.

- Telecommunications and computing: Cell tower coverage areas, clustering in data science and nearest neighbour search algorithms.

📐 IA Spotlight

- Use real locations from your city (schools, clinics, bus stops) and create a Voronoi diagram on graph paper or using technology. Analyse which households are closest to which facility.

- Investigate how adding a new site (for example, a new clinic) changes the sizes of Voronoi cells and shifts boundaries of service areas.

- Explore relationships between cell area and underlying data like population or rainfall, discussing limitations of nearest neighbour interpolation.

🔍 TOK Perspective

- Voronoi diagrams show how we divide continuous space into discrete regions based on a chosen rule (nearest site). To what extent is this division a natural feature of the world, and to what extent is it a human-made model?

- Different disciplines (geography, biology, economics, computer science) use the same mathematical structure. Does this support the idea that mathematics provides a shared language across areas of knowledge?

📝 Paper Tips

- Label sites clearly and sketch a rough Voronoi diagram if not provided; this helps identify which region a point belongs to.

- When asked for a boundary equation, remember it is a perpendicular bisector, so find midpoint and negative reciprocal gradient carefully.

- For “nearest site” questions, compare squared distances when possible to avoid unnecessary square roots; the smallest squared distance gives the nearest site.

- In “toxic waste dump” questions, focus on vertices where three regions meet and compare their distances to all sites systematically.