A2.3.3 – ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF VIRUSES

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

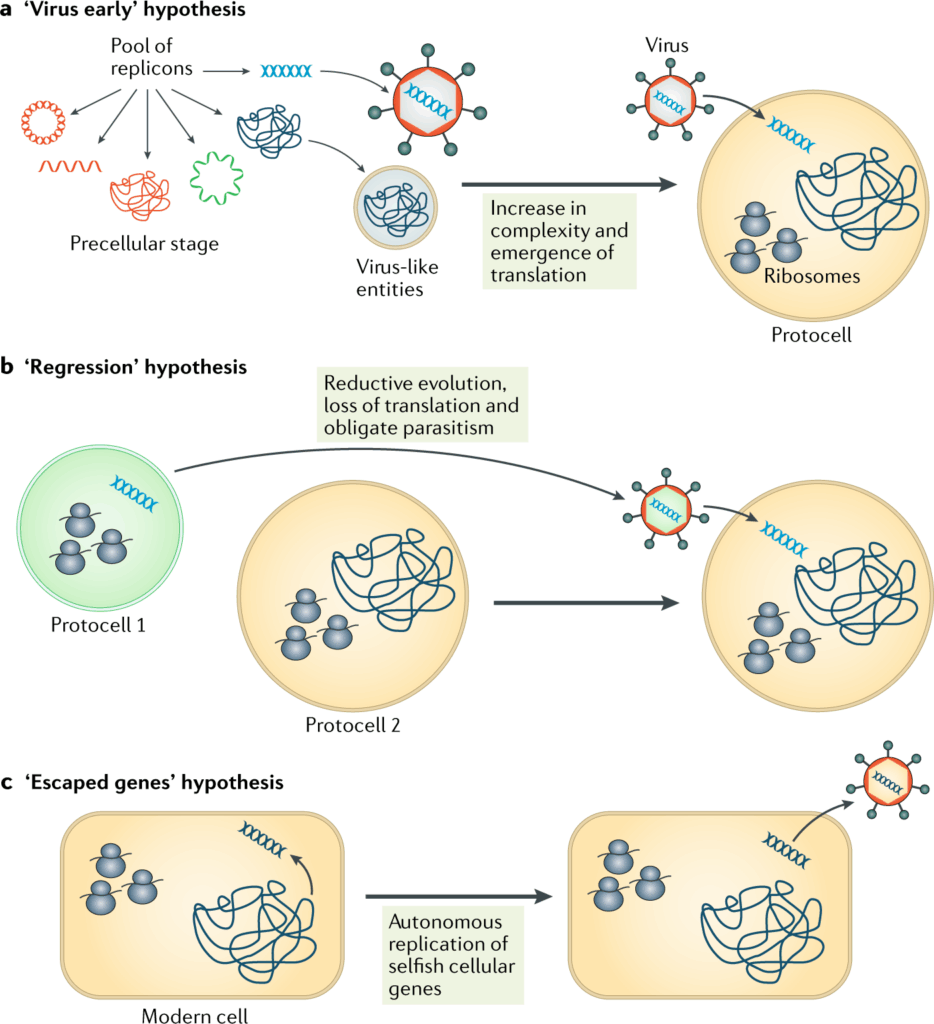

| Escape Theory | Hypothesis that viruses evolved from bits of cellular nucleic acids that “escaped” from their host cells. |

| Regressive Theory | Hypothesis that viruses evolved from more complex free-living organisms that lost cellular structures over time. |

| Virus-First Theory | Hypothesis that viruses existed before cells and contributed to early molecular evolution. |

| Endogenous Retrovirus | Viral sequences that have become permanently integrated into the host genome. |

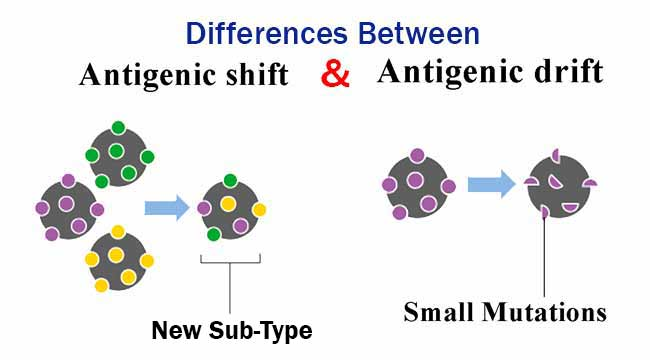

| Antigenic Drift | Gradual accumulation of mutations in viral genes, leading to minor changes in antigens. |

| Antigenic Shift | Major genetic changes due to reassortment of genome segments, often producing new viral strains. |

📌Introduction

The origin and evolution of viruses remain subjects of scientific debate, with multiple hypotheses proposing different pathways. Viruses evolve rapidly due to high mutation rates, recombination, and reassortment of genetic material, enabling them to adapt to new hosts and evade immune responses. Understanding their evolution is critical for controlling viral diseases and developing effective vaccines.

❤️ CAS Link: Create a public science display showing the different theories of virus origin and how rapid viral evolution impacts human health (e.g., flu vaccine updates).

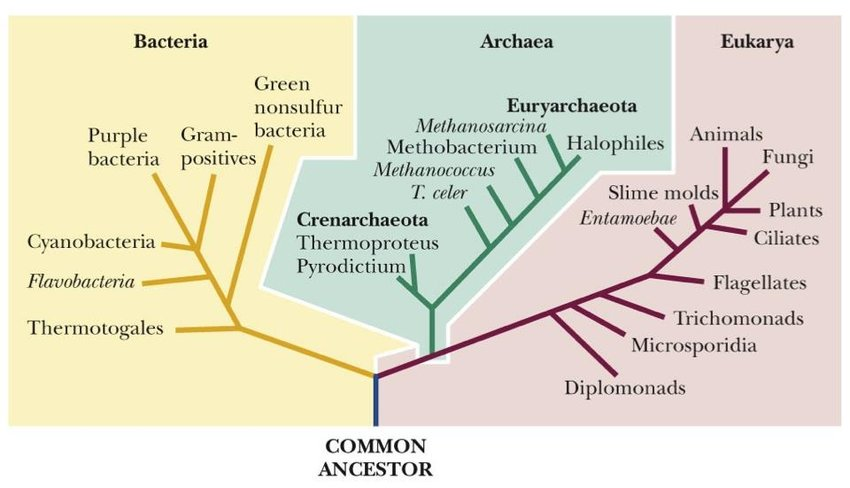

📌 Theories on the Origin of Viruses

- Escape Theory: Viruses originated from fragments of genetic material that “escaped” from cells.

- Regressive Theory: Viruses evolved from cellular organisms that gradually lost complexity.

- Virus-First Theory: Viruses predate cells and were part of pre-cellular life forms.

- These theories are not mutually exclusive — different viruses may have different origins.

- Evidence is limited due to lack of viral fossils and rapid mutation rates.

- Molecular analysis helps trace evolutionary relationships between viruses and hosts.

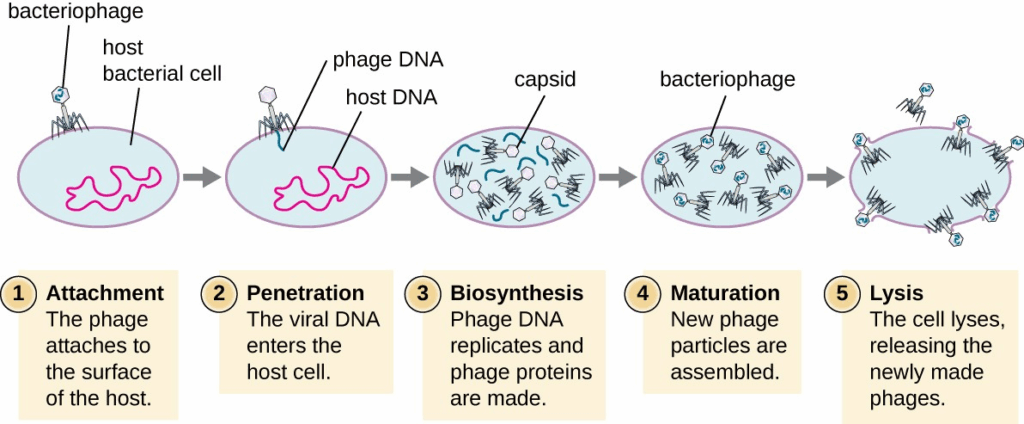

📌 Viral Evolution and Mutation

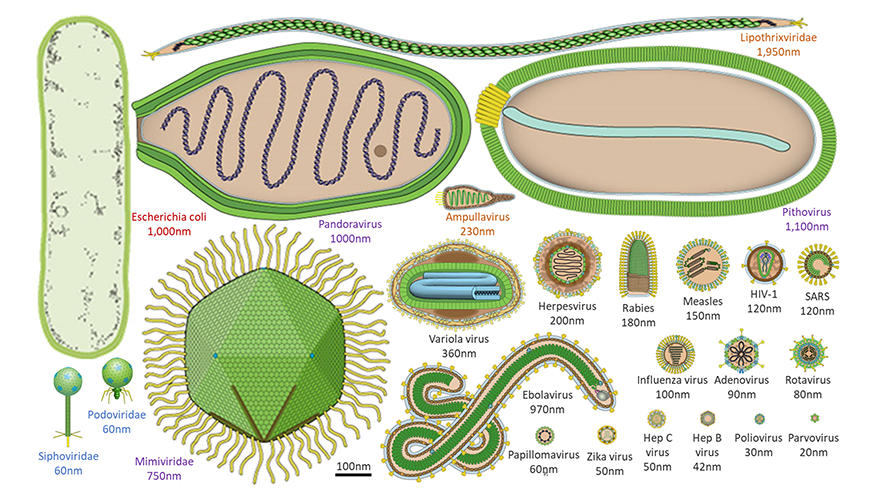

- RNA viruses mutate faster than DNA viruses due to error-prone replication.

- High mutation rates allow viruses to quickly adapt to host immune systems.

- Mutations can alter viral surface proteins, affecting infectivity and host range.

- Recombination occurs when two viruses infect the same cell and exchange genetic material.

- Reassortment in segmented viruses (e.g., influenza) can produce entirely new strains.

- Viral evolution impacts vaccine effectiveness and antiviral drug resistance.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Seasonal influenza vaccines must be updated annually because antigenic drift changes viral surface proteins.

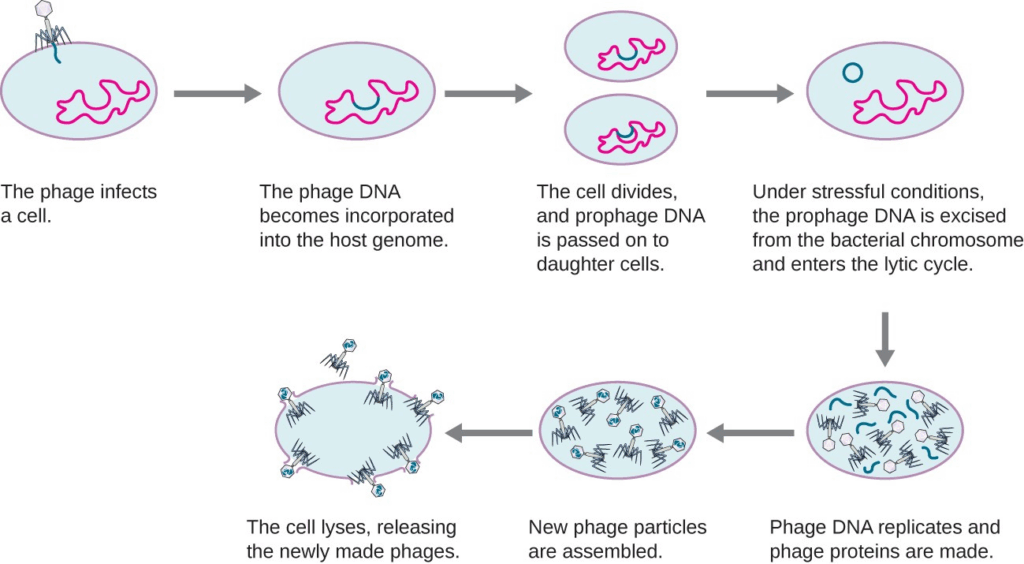

📌 Antigenic Drift vs Antigenic Shift

- Antigenic Drift: Gradual changes due to point mutations in viral genes.

- Antigenic Shift: Abrupt changes due to gene segment reassortment, producing novel antigens.

- Drift leads to reduced vaccine effectiveness over time.

- Shift can cause pandemics when a new strain emerges that the population lacks immunity against.

- Influenza A viruses are well-known for undergoing both drift and shift.

- Shift often occurs when viruses from different species exchange genetic material.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Without direct fossil evidence, how reliable are molecular comparisons in reconstructing viral history?

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how mutation rates in RNA viruses correlate with host immune evasion.