This topic covers numerical summaries of data, including measures of central tendency, dispersion,

and the effects of changing data values. These tools help us understand distribution shapes, compare

two datasets, and evaluate the reliability of conclusions drawn from sample data.

1. Measures of Central Tendency

Mean

The mean is calculated by summing all values and dividing by the number of items. It is highly

sensitive to extreme values, meaning it works best for fairly symmetrical distributions.

Median

The median represents the middle value of a sorted dataset. Since it is unaffected by outliers or

large extreme values, it is an appropriate measure for skewed distributions.

Mode

The most frequent value in the data. Especially useful for categorical or discrete data.

🌍 Real-World Example:

Income data is typically summarised using the median, not the mean,

because a few very high earners can distort the average.

Estimation of Mean from Grouped Data

For grouped data, mid-interval values are used as representatives. Multiply each midpoint by its

frequency, sum these products, and divide by the total frequency to estimate the mean.

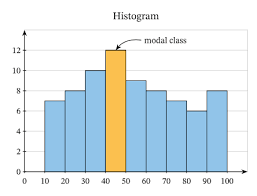

2. Modal Class

For grouped data with equal intervals, the modal class is the class with the highest frequency.

This is useful when exact data values are not available.

444 × 339

3. Measures of Dispersion

Interquartile Range (IQR)

The IQR measures the spread of the middle 50% of the data. It is resistant to outliers and gives a

clearer picture of the central distribution’s variability.

Variance and Standard Deviation

Variance measures the average squared deviation from the mean. The standard deviation, its square root,

measures the typical distance from the mean and is widely used for statistical comparison.

🌍 Real-World Example:

In sports analytics, standard deviation measures consistency.

An athlete with a low SD performs reliably across games.

4. Effect of Constant Changes

• Adding a constant to all data values shifts the mean by that constant but does not change the standard deviation.

• Multiplying all values by a constant multiplies both the mean and the standard deviation by that constant.

🧠 Examiner Tip:

Students often forget that adding or subtracting a constant does not change the

spread of data. Only multiplication affects spread.

5. Quartiles of Discrete Data

Quartiles divide data into four equal parts. Different calculators may use different algorithms, so results

may differ slightly between hand calculation and GDC output.

🟢 GDC Tip:

When using a calculator to compute quartiles or standard deviation, always write

“Using GDC” in your work to show that you are aware of algorithmic differences.

🔍 TOK Perspective:

Why do multiple formulas for variance exist? Does this imply that mathematical truth can have

multiple valid representations?

📊 IA Suggestion:

Investigate whether different sports, cities, or environmental datasets show greater variability.

Justify your choice of mean, median, IQR, and SD in your analysis.

❤️ CAS Connection:

Collect real data during a community activity (fitness, volunteering outputs, environmental waste)

and analyse its central tendency and spread as part of CAS reflections.