B3.3.2 – MECHANISM OF MUSCLE CONTRACTION

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Myofibril | Cylindrical organelle within a muscle fibre, composed of repeating units called sarcomeres. |

| Sarcomere | The basic contractile unit of muscle, consisting of actin and myosin filaments between two Z-lines. |

| Sliding Filament Model | Explanation of muscle contraction where actin and myosin filaments slide past each other to shorten the sarcomere. |

| Tropomyosin | Regulatory protein that covers myosin-binding sites on actin in resting muscle. |

| Troponin | Regulatory protein complex that binds calcium ions to initiate muscle contraction. |

| Titin | Elastic protein that helps maintain sarcomere structure and allows passive recoil after stretching. |

📌Introduction

Muscle contraction is a finely tuned process that transforms chemical energy from ATP into mechanical work through the interaction of protein filaments. This process requires precise regulation by calcium ions, ATP hydrolysis, and regulatory proteins to ensure coordinated movement. The sliding filament model is the central explanation for contraction in skeletal, cardiac, and some smooth muscles, although regulatory mechanisms differ among muscle types.

❤️ CAS Link: Lead a workshop demonstrating muscle contraction using physical models and elastic bands to simulate actin–myosin interactions for younger students

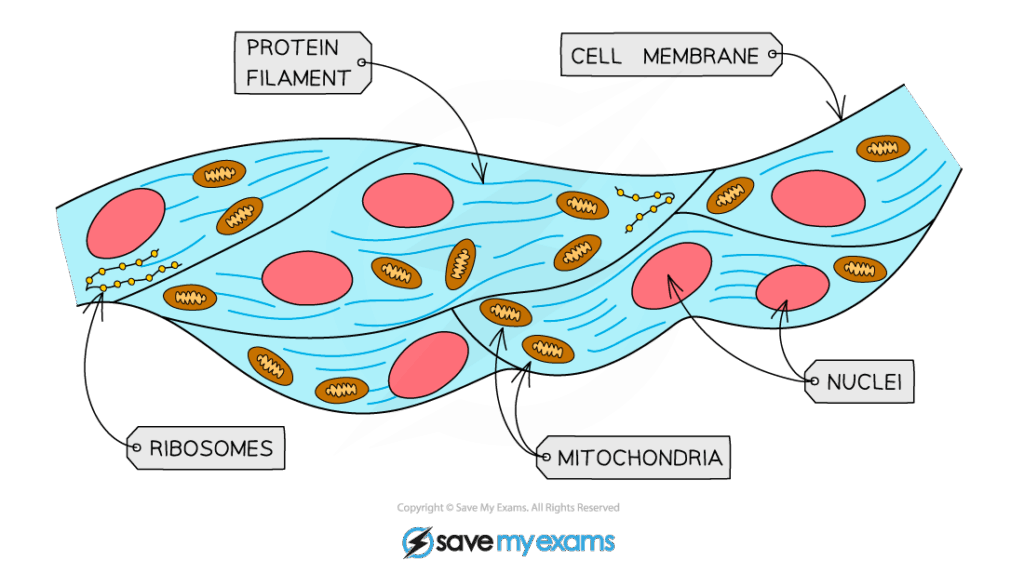

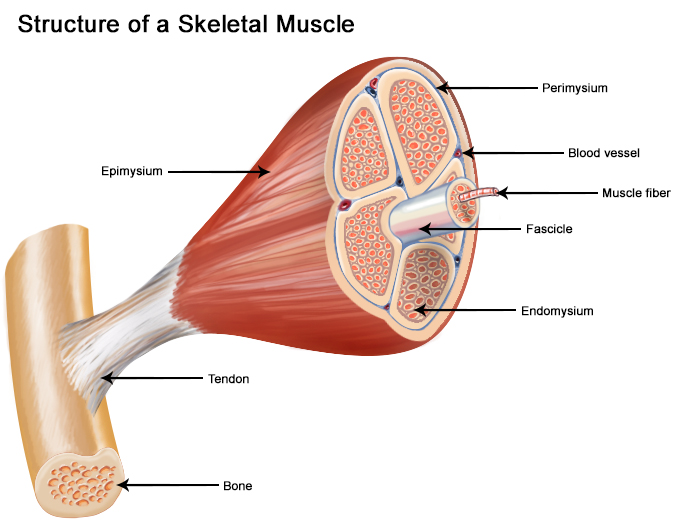

📌 Structure of Skeletal Muscle

- Muscle fibres are long, multinucleated cells formed from fused myoblasts.

- Each fibre contains numerous myofibrils aligned in parallel for maximum force generation.

- Myofibrils are composed of repeating sarcomeres with distinct A bands (dark) and I bands (light).

- Sarcomeres contain thick filaments (myosin) and thin filaments (actin, tropomyosin, troponin).

- The sarcoplasmic reticulum surrounds myofibrils and stores calcium ions for contraction.

🧠 Examiner Tip: In diagram questions, label at least Z-line, A band, I band, H zone, M line to secure full marks.

📌 Initiation of Muscle Contraction

- Nerve impulse reaches neuromuscular junction, releasing acetylcholine into the synaptic cleft.

- Acetylcholine binds to receptors on the muscle fibre membrane, triggering depolarisation.

- Depolarisation spreads along the sarcolemma and down T-tubules to the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

- Calcium ions are released into the cytosol from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

- Calcium binds to troponin, causing tropomyosin to shift and expose myosin-binding sites on actin.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Many toxins and drugs (e.g., botulinum toxin, curare) act at the neuromuscular junction, blocking contraction and causing paralysis.

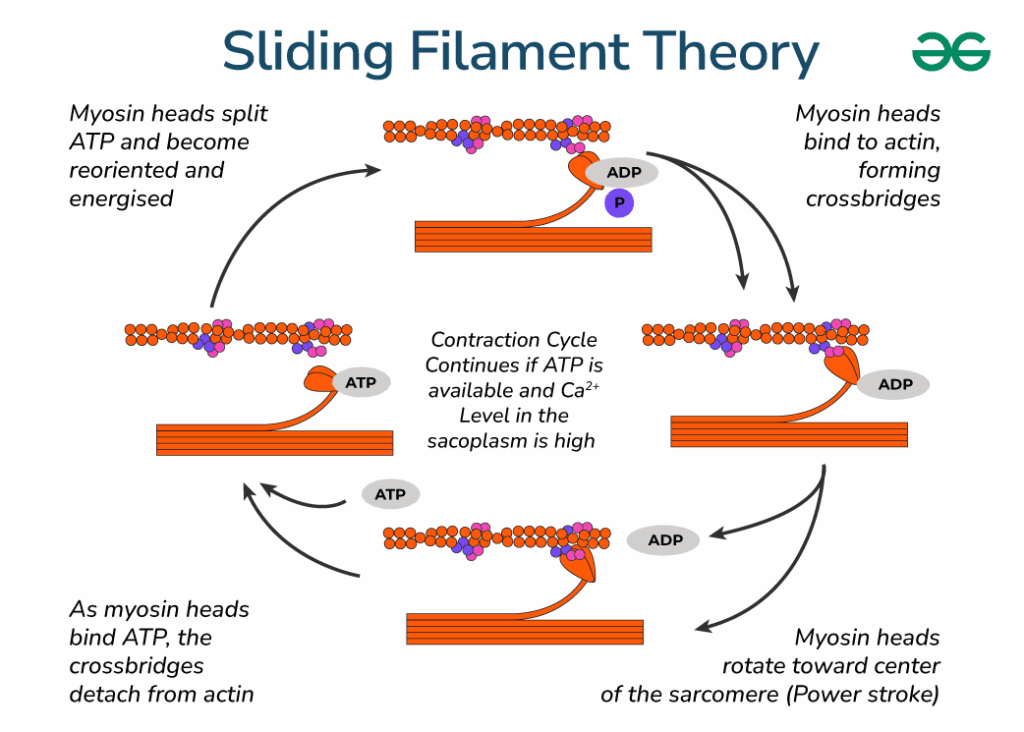

📌 The Sliding Filament Model

- Myosin heads bind to exposed actin sites, forming cross-bridges.

- Myosin heads pivot, pulling actin filaments toward the centre of the sarcomere (power stroke).

- ATP binds to myosin heads, causing them to detach from actin.

- ATP is hydrolysed to ADP + Pi, re-cocking the myosin heads for another cycle.

- Continuous cycles of cross-bridge formation and release shorten the sarcomere, producing contraction.

🔍 TOK Perspective: The sliding filament model is a simplification — molecular imaging has revealed more complex filament interactions than originally thought.

📌 Role of Titin and Elastic Components

- Titin spans from Z-line to M-line, stabilising myosin filaments and centring them in the sarcomere.

- Acts as a molecular spring, storing elastic energy during stretching.

- Contributes to passive muscle tension and prevents overstretching.

- Assists in sarcomere recoil after contraction.

- Its elasticity is crucial for smooth, coordinated movement.

⚗️ IA Tips & Guidance: An IA could measure contraction force in isolated muscle fibres under varying calcium concentrations to explore ion regulation in muscle contraction.

📌 Muscle Relaxation

- Nerve stimulation stops, and acetylcholine is broken down by acetylcholinesterase.

- Calcium ions are actively pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum using ATP.

- Troponin returns to its resting shape, allowing tropomyosin to block actin-binding sites.

- Cross-bridge cycling stops, and the sarcomere returns to resting length.

- Passive elastic elements restore muscle to pre-contraction position.