A1.2.2 – FUNCTION AND ROLE OF THE GENETIC CODE

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Genetic Code | The set of rules by which nucleotide sequences are translated into amino acid sequences in proteins. |

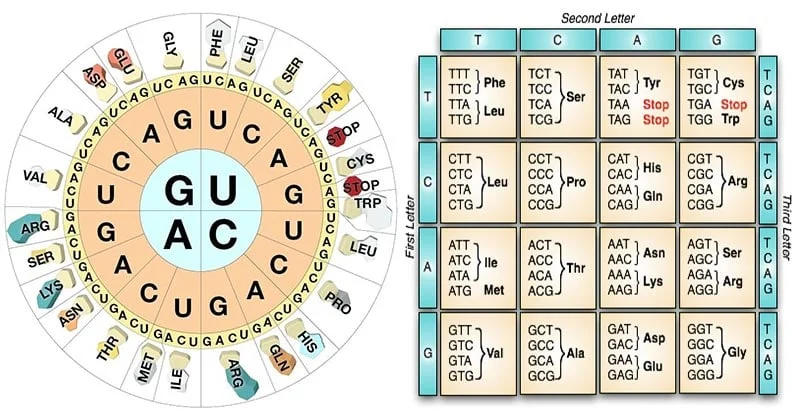

| Codon | A triplet of nucleotides in mRNA that codes for a specific amino acid or a stop signal. |

| Start Codon | AUG; signals the start of translation and codes for methionine. |

| Stop Codon | UAA, UAG, UGA; signals the end of translation. |

| Degeneracy | Multiple codons can code for the same amino acid. |

| Reading Frame | The way nucleotides are grouped into codons during translation. |

📌Introduction

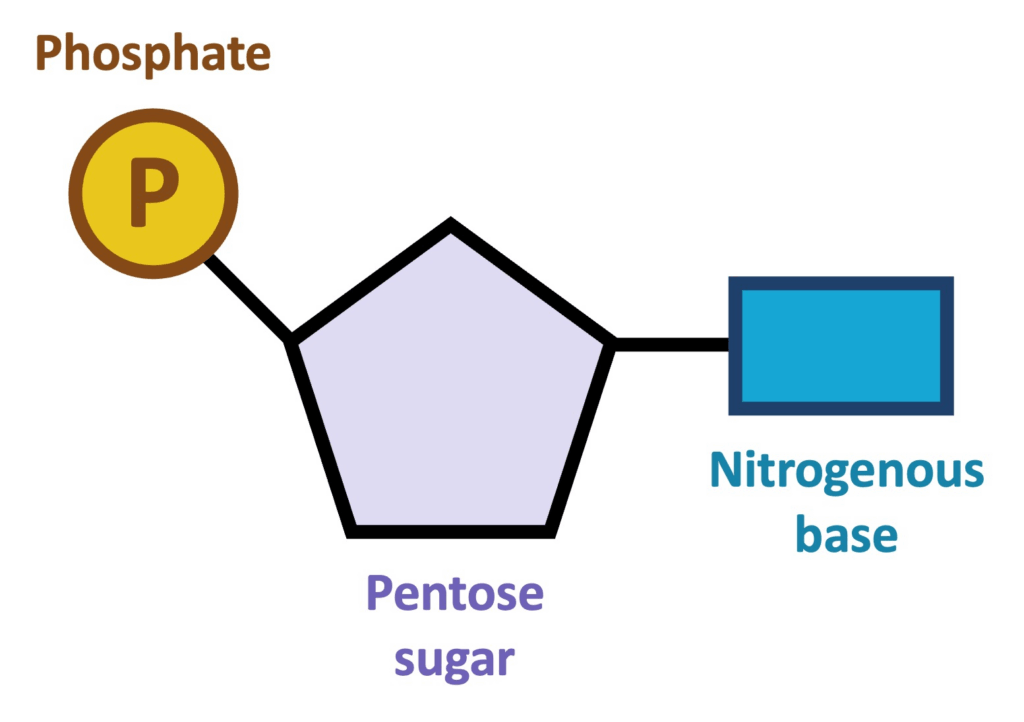

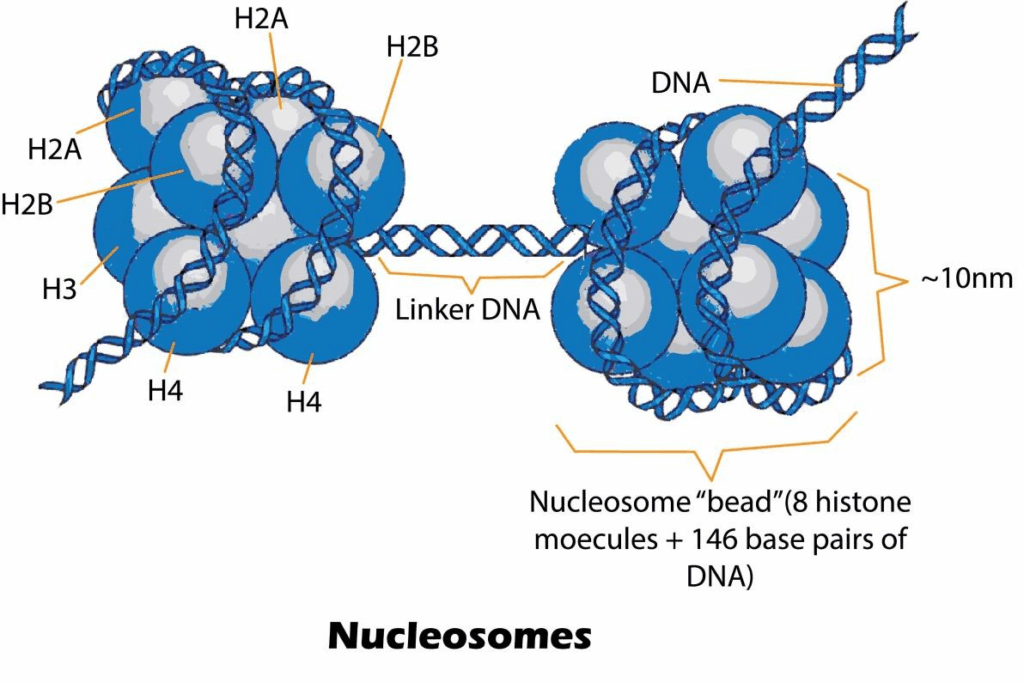

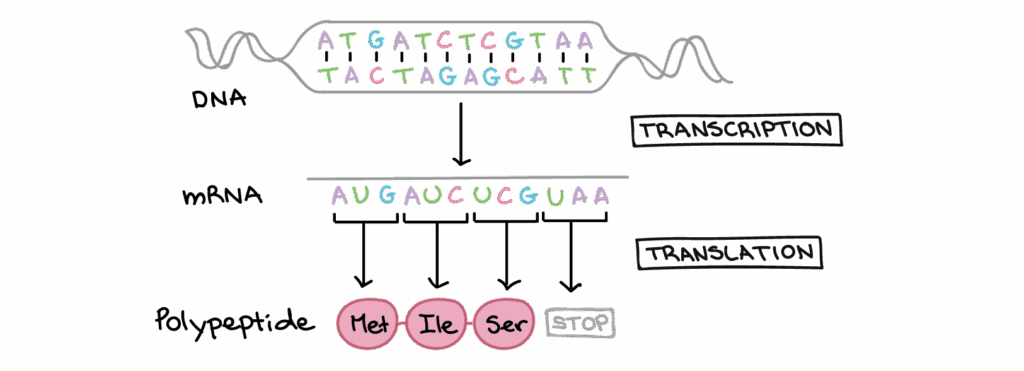

The genetic code is a universal molecular language linking DNA sequences to protein structures. It ensures accurate transfer of genetic instructions from DNA to functional proteins through transcription and translation.

📌 Properties of the Genetic Code

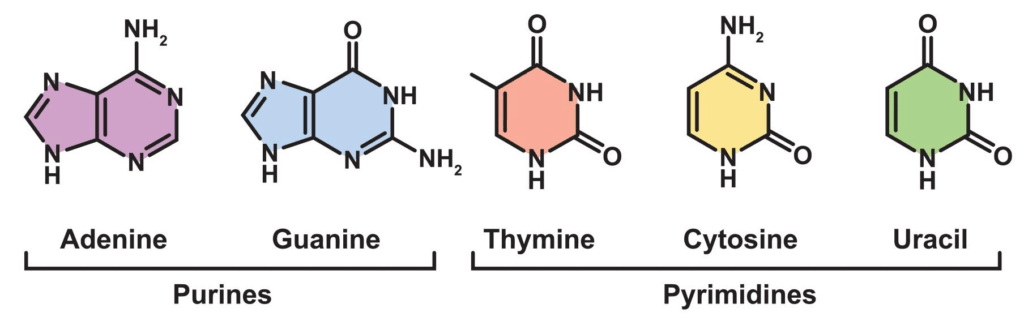

- Triplet Nature: Each amino acid is specified by a three-nucleotide codon.

- Degenerate: Most amino acids have more than one codon, reducing mutation effects.

- Unambiguous: Each codon codes for only one amino acid.

- Non-Overlapping: Codons are read sequentially without sharing bases.

- Universal: Shared by almost all organisms (with minor exceptions in mitochondria).

- Start/Stop Signals: AUG starts translation; UAA, UAG, UGA stop it.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always specify the start codon (AUG) and stop codons in answers about translation.

📌 Role in Transcription

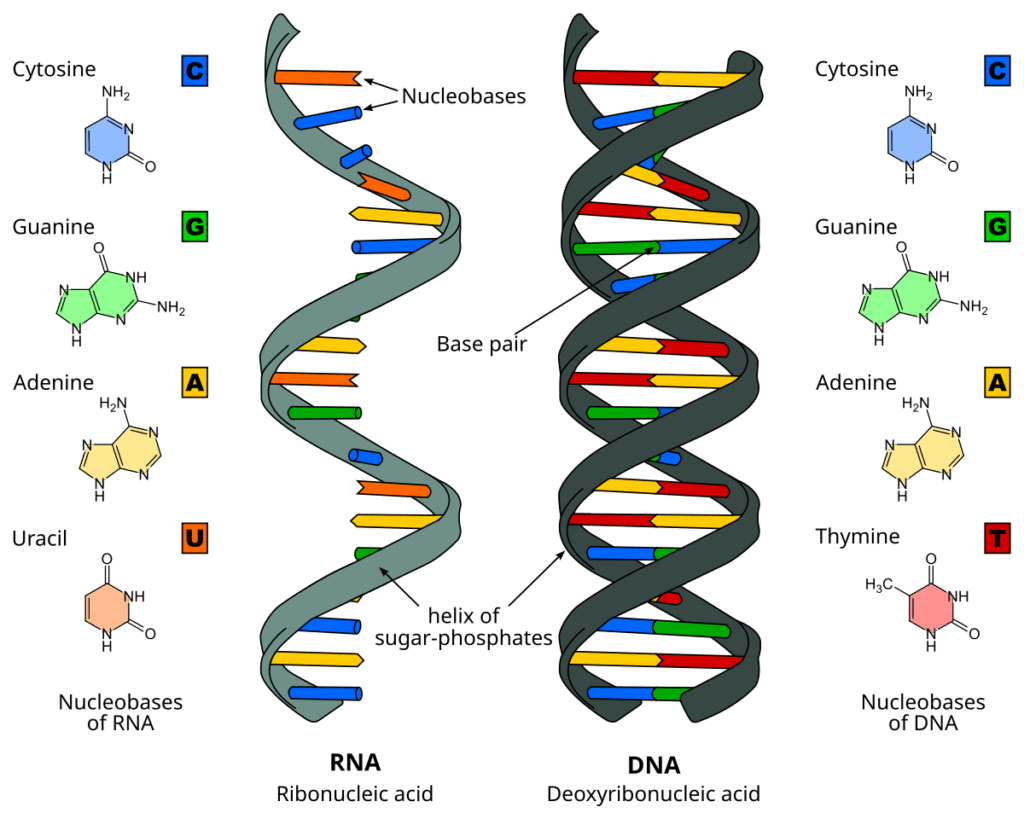

- DNA sequence is copied into mRNA by RNA polymerase.

- Uses complementary base pairing (A–U, G–C).

- Only one strand (template strand) is transcribed.

- Promoter regions control where transcription begins.

- mRNA produced is complementary to the DNA template strand.

- Errors in transcription can lead to incorrect proteins.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Measure transcription rates under different temperature or pH conditions using in vitro transcription systems.

📌 Role in Translation

- Ribosomes read mRNA codons in the 5′ → 3′ direction.

- tRNA molecules carry specific amino acids to the ribosome.

- Anticodon in tRNA pairs with codon in mRNA.

- Peptide bonds form between amino acids.

- Process continues until a stop codon is reached.

- Produces a specific polypeptide chain.

🌐 EE Focus: Investigate how codon bias affects translation efficiency in different organisms.

📌 Start and Stop Codons

- Start: AUG — codes for methionine; establishes reading frame.

- Stops: UAA, UAG, UGA — do not code for amino acids.

- Misreading start/stop sites can produce non-functional proteins.

- Mutations in these sites can disrupt protein synthesis.

- Alternative start codons exist in rare cases.

❤️ CAS Link: Create a classroom activity where students decode amino acid sequences from mRNA codons.

📌 Degeneracy and Mutation Protection

- Reduces harmful effects of point mutations.

- Silent mutations often occur at the third codon position.

- Codon families group codons with the same amino acid outcome.

- Evolutionary adaptation to minimize protein errors.

- Some codons are more common (codon bias).

🌍 Real-World Connection: Codon optimization is used in biotechnology to improve protein expression in recombinant DNA systems.

📌 Universality and Evolution

- Shared by most life forms — evidence for common ancestry.

- Minor variations exist in mitochondrial and some microbial codes.

- Supports evolutionary conservation of molecular machinery.

- Changes in code are rare due to complexity of translation system.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Universality of the genetic code raises questions about whether life shares a single origin or if convergent evolution could produce the same code.