A3.2.1 – BIOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Biological Classification | The systematic arrangement of living organisms into groups based on similarities and evolutionary relationships. |

| Taxonomy | The science of naming, describing, and classifying organisms. |

| Systematics | The study of biological diversity and the evolutionary relationships among organisms. |

| Binomial Nomenclature | A universal naming system assigning each species a two-part name: genus and species. |

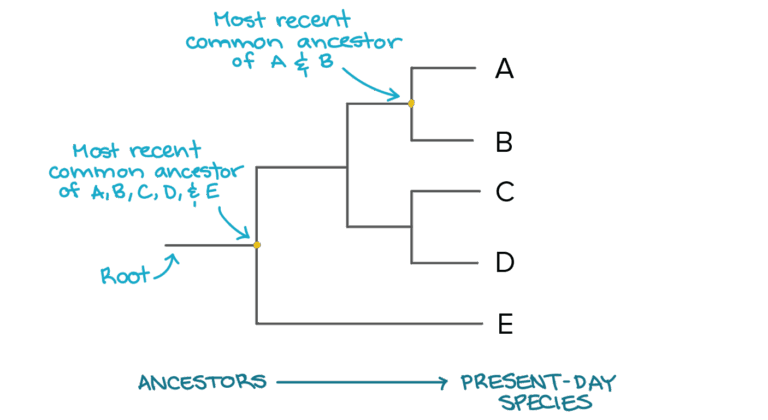

| Taxonomic Hierarchy | The ordered ranking of taxa from broad to specific: domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. |

📌Introduction

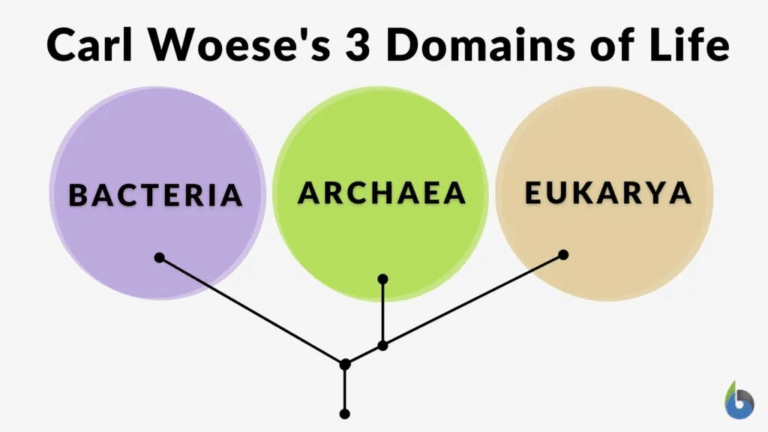

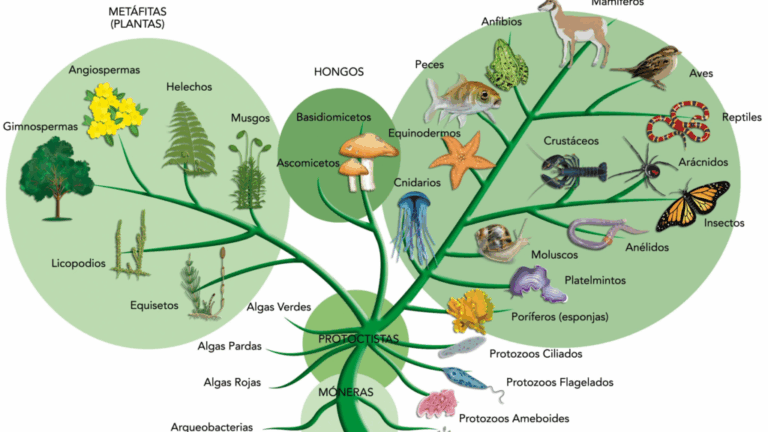

Biological classification provides a framework for organising the immense diversity of life on Earth. By grouping organisms based on shared features and genetic relationships, scientists can communicate effectively, make predictions about unknown species, and understand evolutionary history. The system originated with Carl Linnaeus’s morphological approach and has since evolved to incorporate molecular data, making classification more accurate and reflective of true phylogenetic relationships.

📌 Importance of Classification

- Organises biodiversity into manageable and meaningful groups.

- Enables clear communication among scientists worldwide through standardised naming.

- Provides insights into evolutionary relationships between organisms.

- Helps predict characteristics of newly discovered organisms.

- Supports conservation efforts by identifying species and their roles in ecosystems.

- Facilitates research by grouping organisms with similar traits.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always italicise genus and species names and capitalise only the genus when writing binomial nomenclature (e.g., Homo sapiens).

📌 Principles of Biological Classification

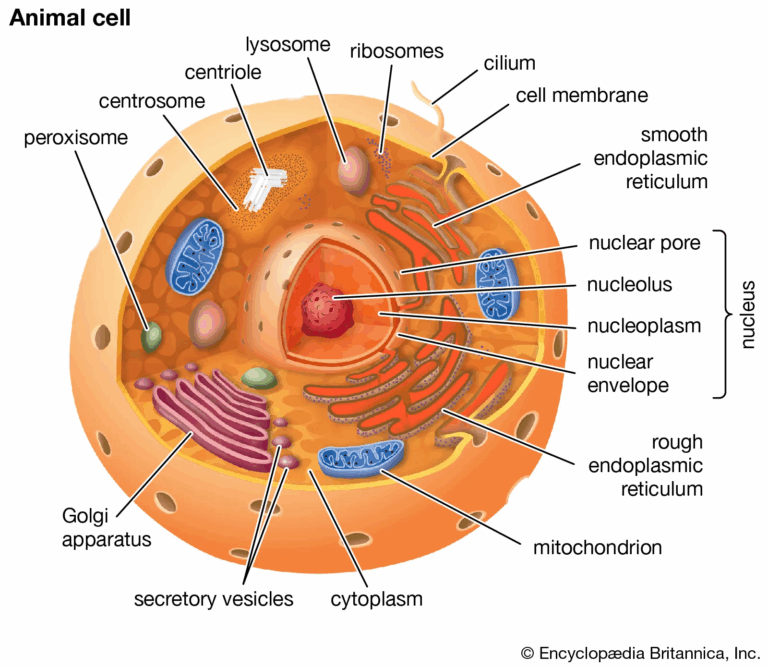

- Based on observable characteristics and genetic similarities.

- Uses a hierarchical system of ranks from broad to specific.

- Includes both morphological and molecular evidence.

- Reflects evolutionary history wherever possible.

- Employs binomial nomenclature for universal identification.

- Allows for flexibility and revision as new data emerge.

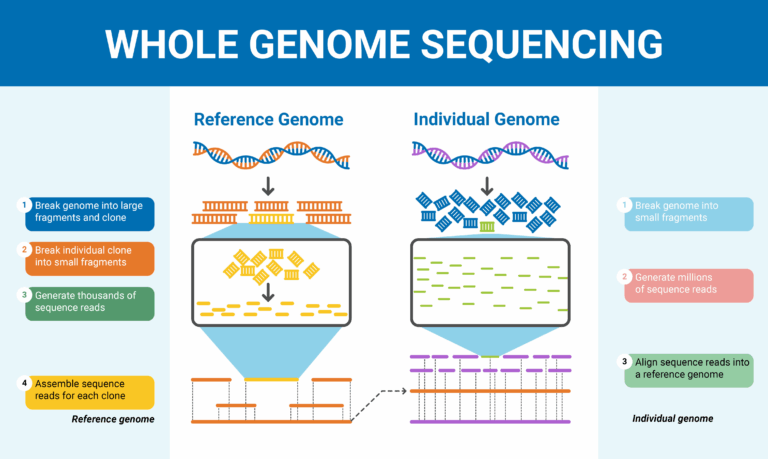

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: A possible IA could compare species identification using morphological keys versus DNA barcoding techniques.

📌 Types of Classification Systems

- Artificial systems: Based on one or few characteristics, often for convenience (e.g., habitat or size).

- Natural systems: Based on multiple characteristics reflecting evolutionary relationships.

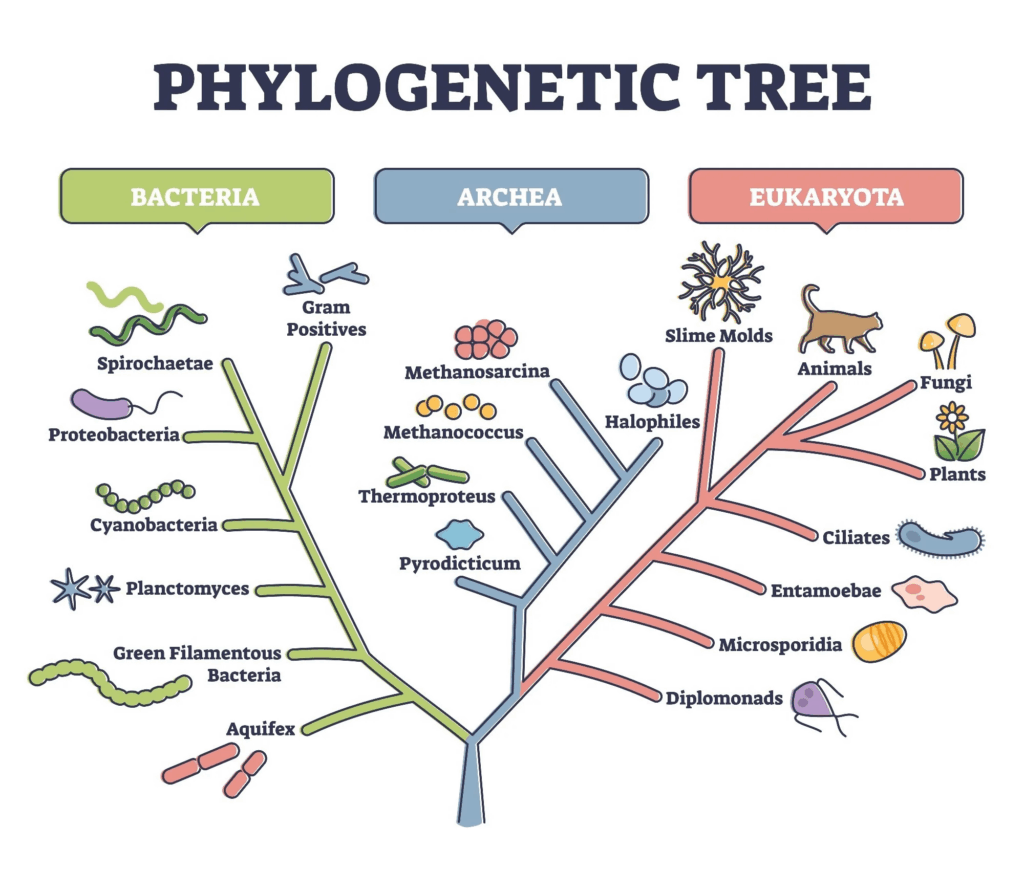

- Phylogenetic systems: Focused on common ancestry using morphological and molecular data.

- Systems can shift as new technologies and evidence become available.

- Phylogenetic classification is currently the most accepted method.

- Fossil evidence can be integrated into classification.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could analyse how molecular evidence has reshaped classification within a specific group of organisms.

📌 Tools in Biological Classification

- Dichotomous keys for identification.

- Field guides for local species.

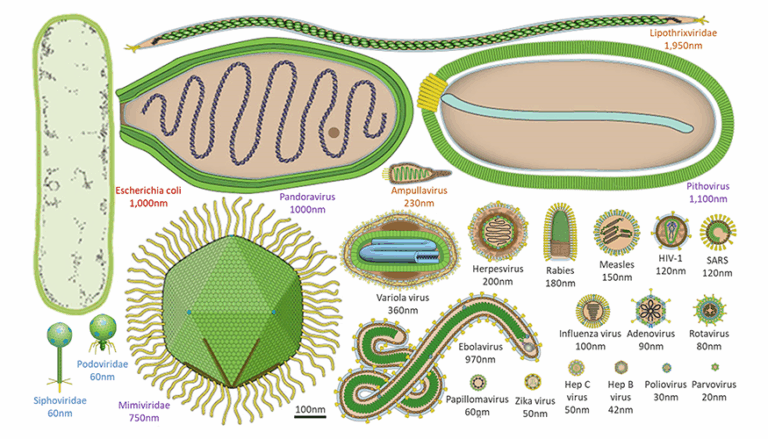

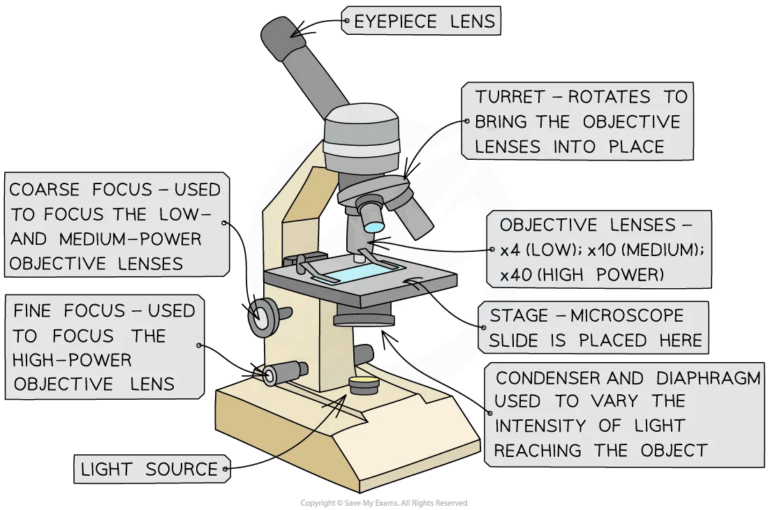

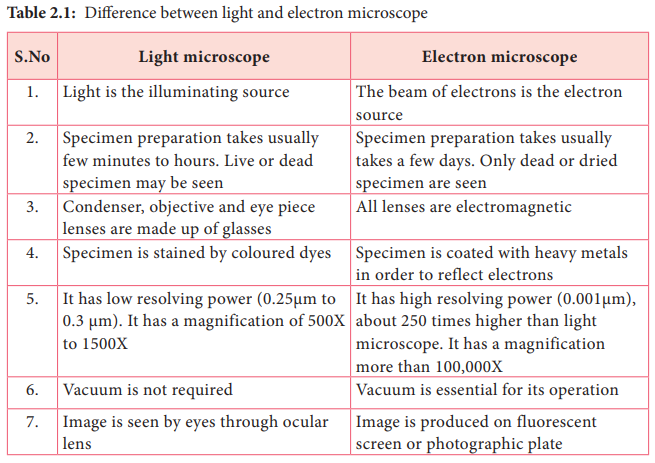

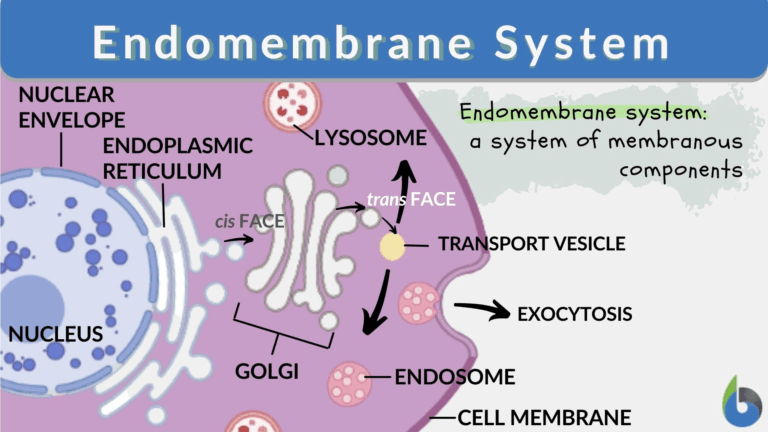

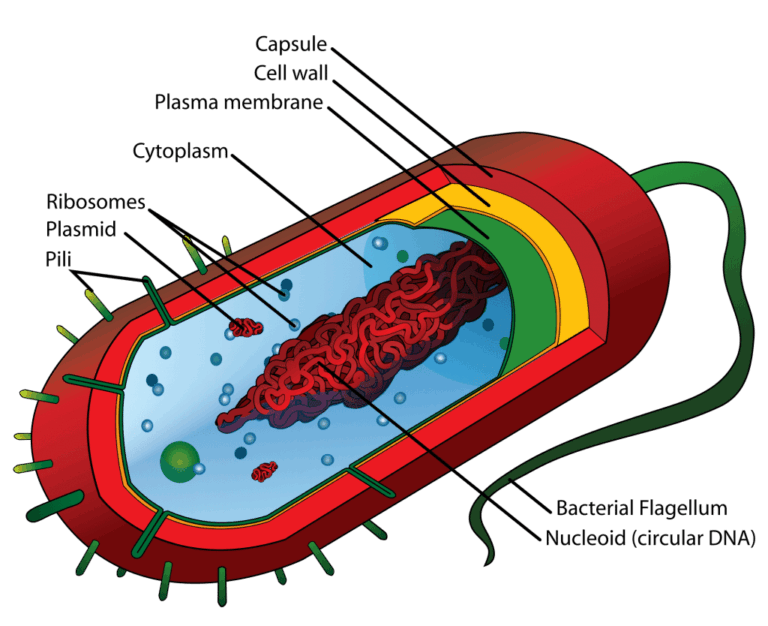

- Microscopy for cellular characteristics.

- DNA sequencing for molecular comparisons.

- Bioinformatics for analysing large datasets.

- Phylogenetic software for tree construction.

❤️ CAS Link: A CAS project could involve creating a field guide for local biodiversity, integrating both scientific names and common names.

📌 Limitations and Challenges

- Morphological similarities may be due to convergent evolution, not shared ancestry.

- Genetic data may conflict with traditional classification.

- Hybridisation can blur species boundaries.

- Cryptic species may remain undetected without molecular analysis.

- Classification is dynamic — constant updates are required.

- Human bias can influence early classification decisions.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Classification systems reflect human attempts to impose order on nature; changes in technology and perspective can reshape these systems over time.

🌍 Real-World Connection:

Accurate classification underpins agriculture, medicine, conservation, and environmental policy by ensuring correct species identification.