A2.2.2 – EUKARYOTIC CELL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Eukaryote | An organism whose cells contain a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. Includes plants, animals, fungi, and protists. |

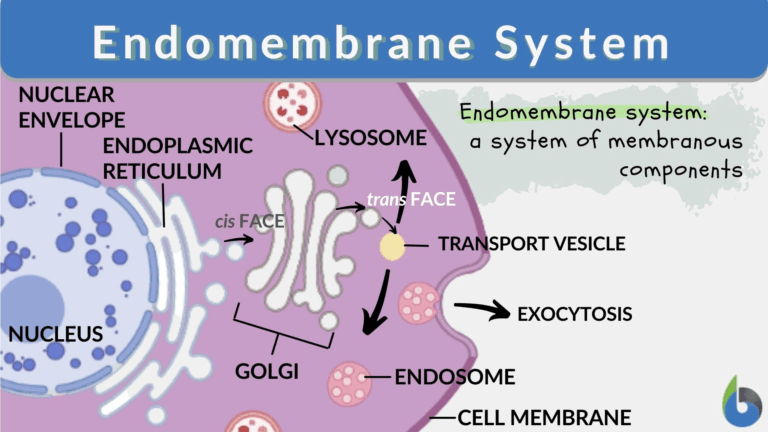

| Endomembrane System | Network of membranes within the cell that synthesises, processes, and transports molecules. |

| Cytoskeleton | Network of protein filaments providing structural support, intracellular transport, and cell movement. |

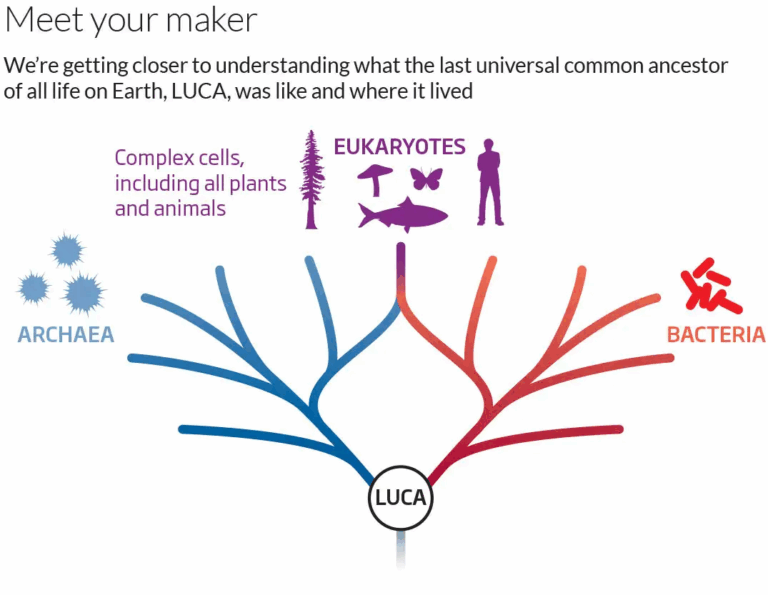

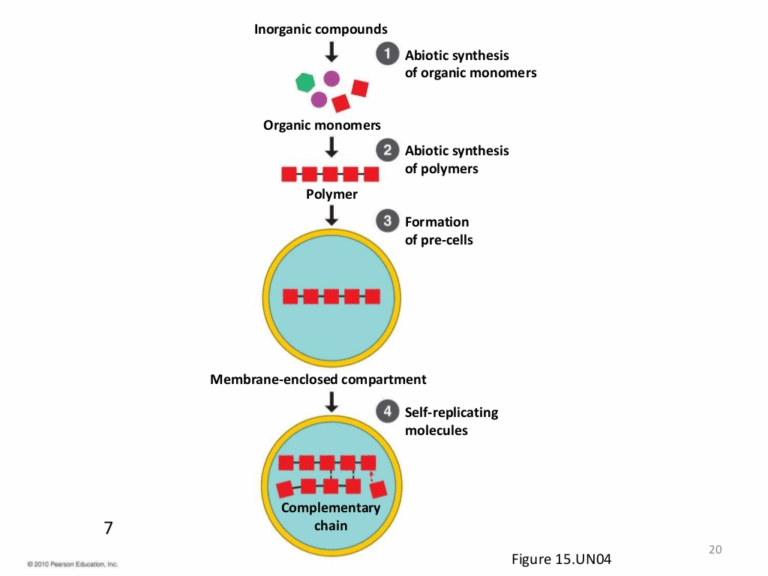

| Endosymbiotic Theory | Hypothesis that mitochondria and chloroplasts originated from free-living prokaryotes engulfed by ancestral eukaryotic cells. |

| 80S Ribosomes | Larger ribosomes found in eukaryotic cytoplasm, responsible for protein synthesis. |

📌Introduction

Eukaryotic cells are more structurally complex than prokaryotes, containing a true nucleus and numerous membrane-bound organelles. This compartmentalisation allows for greater efficiency in metabolic processes and supports the specialised functions required by multicellular organisms. Eukaryotic cells are thought to have evolved through endosymbiosis, where ancestral cells incorporated prokaryotes that became permanent organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts. Their complexity enables functions such as coordinated signalling, advanced locomotion, and large-scale structural organisation in tissues and organs.

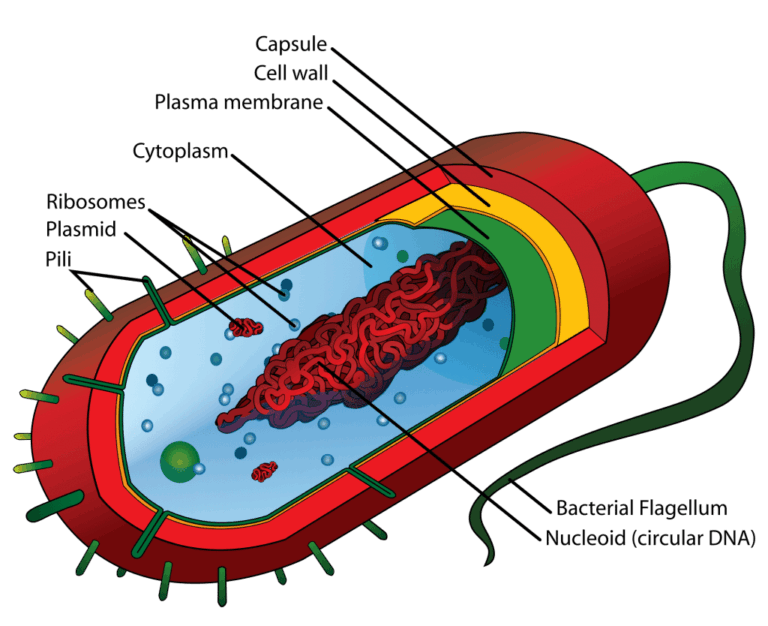

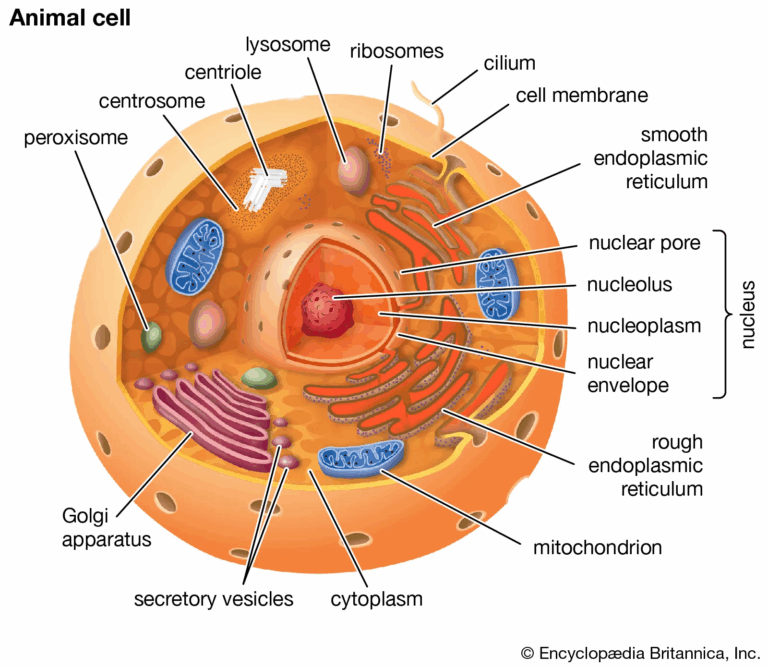

📌 Structure of Eukaryotic Cells

- Nucleus enclosed by a double membrane, containing DNA and nucleolus for ribosome synthesis.

- Endoplasmic reticulum (ER): rough ER (with ribosomes) synthesises proteins; smooth ER synthesises lipids and detoxifies toxins.

- Golgi apparatus modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids for secretion or intracellular use.

- Mitochondria produce ATP through aerobic respiration, containing their own DNA and 70S ribosomes.

- Chloroplasts (in plants/algae) perform photosynthesis and also contain their own DNA and 70S ribosomes.

- Cytoskeleton (microtubules, microfilaments, intermediate filaments) maintains cell shape and enables transport.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always mention that mitochondria and chloroplasts have double membranes and their own DNA/ribosomes as evidence for endosymbiotic theory.

📌 Endosymbiotic Theory Evidence

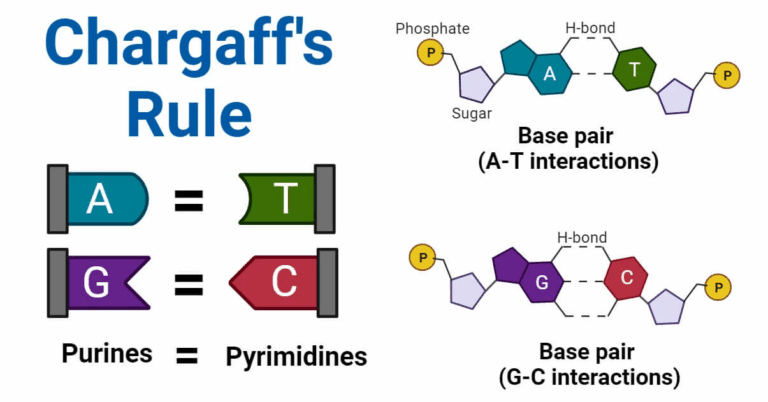

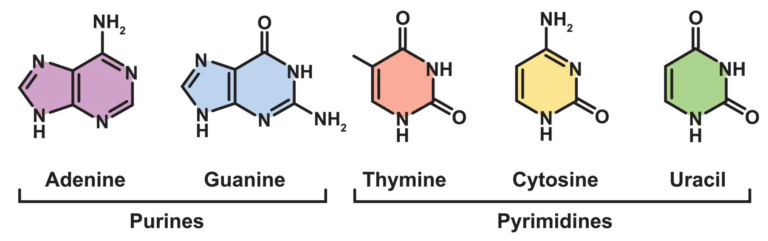

- Mitochondria and chloroplasts are similar in size to prokaryotes.

- Both have double membranes, consistent with engulfing events.

- Both contain circular DNA like bacteria.

- Both have 70S ribosomes, not 80S like the rest of the eukaryotic cell.

- They replicate independently via binary fission.

- Antibiotics that target bacterial ribosomes can also affect these organelles.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: An IA could test effects of specific antibiotics on chloroplast activity in algae to model bacterial ribosome inhibition.

📌 Specialised Eukaryotic Structures

- Cilia and flagella for movement (9+2 microtubule arrangement).

- Lysosomes contain hydrolytic enzymes for digestion and recycling of cellular components.

- Peroxisomes detoxify harmful substances and perform lipid metabolism.

- Vacuoles in plant cells store water, nutrients, and waste.

- Cell wall in plants, fungi, and some protists provides structural support.

- Extracellular matrix (ECM) in animal cells helps with adhesion and signalling.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate differences in cytoskeletal arrangements between animal and plant cells

📌 Functions of Eukaryotic Cells

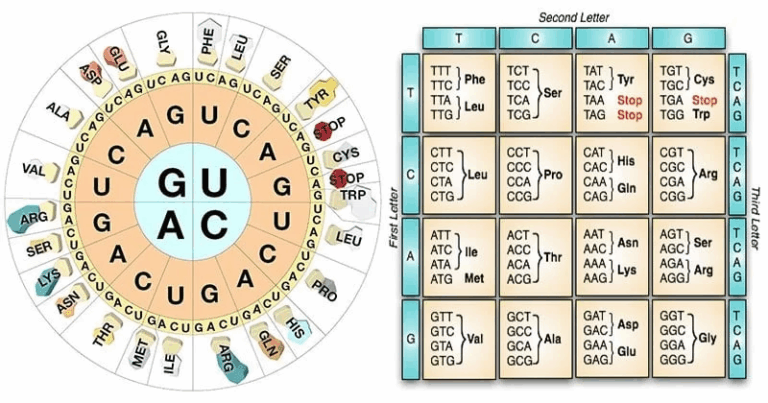

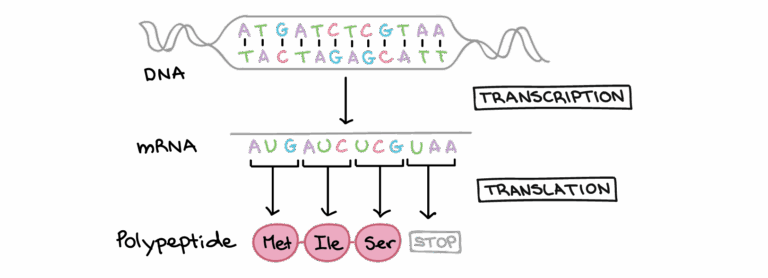

- Genetic control through regulated transcription and translation.

- Energy transformation in mitochondria and chloroplasts.

- Macromolecule synthesis in ER and Golgi apparatus.

- Intracellular transport via vesicles and cytoskeletal tracks.

- Signal transduction through receptor-ligand interactions at the plasma membrane.

- Specialisation in multicellular organisms for tissue-specific functions.

❤️ CAS Link: A CAS activity could involve designing 3D models of

🌍 Real-World Connection:

Understanding eukaryotic structure is essential in medical research, particularly in cancer biology, where organelle function and signalling pathways are often altered.

📌 Microscopy in Eukaryotic Studies

- Light microscopy reveals overall cell structure, organelles like chloroplasts and nucleus.

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) shows internal details like cristae in mitochondria.

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provides 3D surface images of cells.

- Fluorescence microscopy highlights specific organelles or proteins with dyes or GFP.

- Confocal microscopy produces sharper, layered images of thick specimens.

- Advances in microscopy have deepened our understanding of eukaryotic compartmentalisation.

🔍 TOK Perspective: The endosymbiotic theory demonstrates how combining molecular, structural, and evolutionary evidence can