A4.1.3 – ADAPTIVE RADIATION AND SPECIATION IN PLANTS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Adaptive Radiation | The rapid diversification of a single ancestral species into multiple new species, each adapted to a specific ecological niche. |

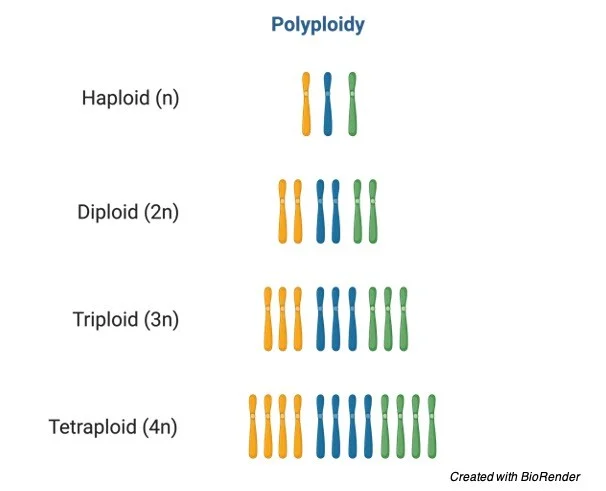

| Polyploidy | The condition in which an organism has more than two complete sets of chromosomes, common in plant speciation. |

| Autopolyploidy | Polyploidy arising from chromosome duplication within a single species. |

| Allopolyploidy | Polyploidy resulting from hybridisation between different species followed by chromosome doubling. |

| Niche Differentiation | The process by which competing species use the environment differently to coexist. |

📌Introduction

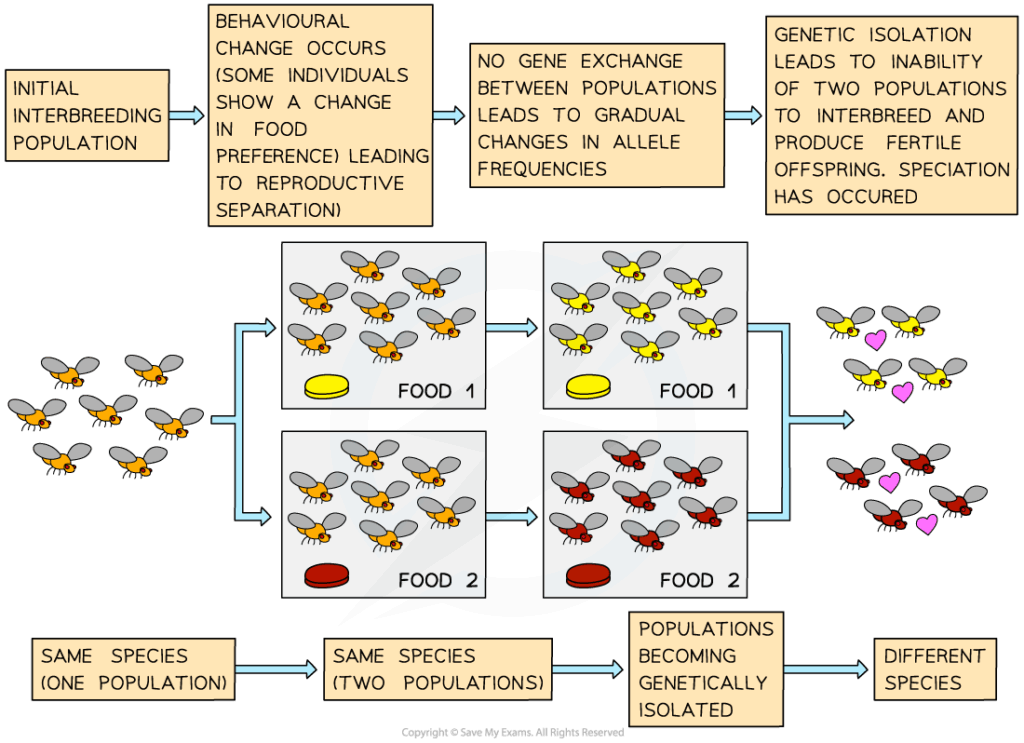

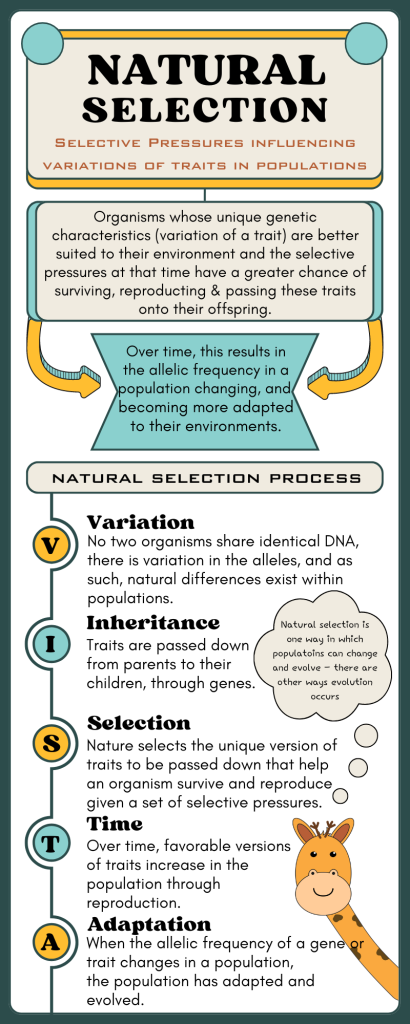

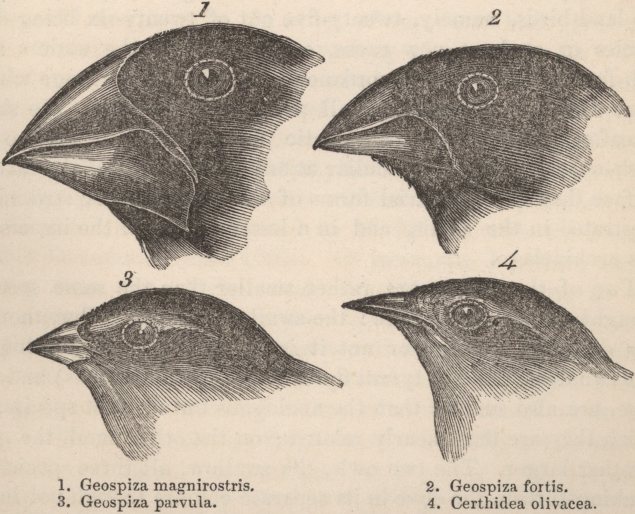

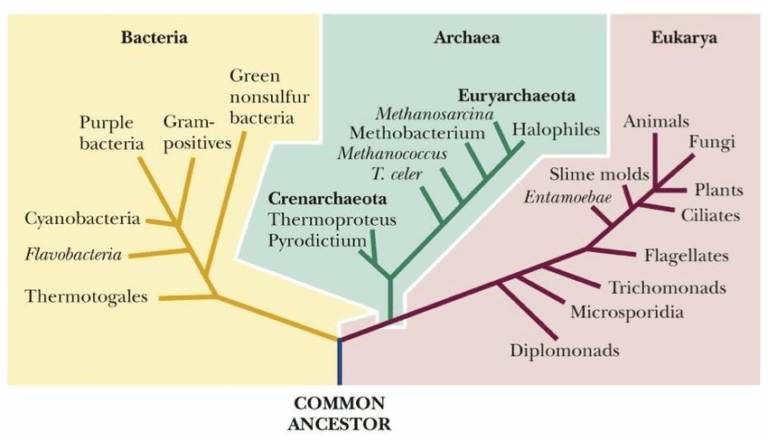

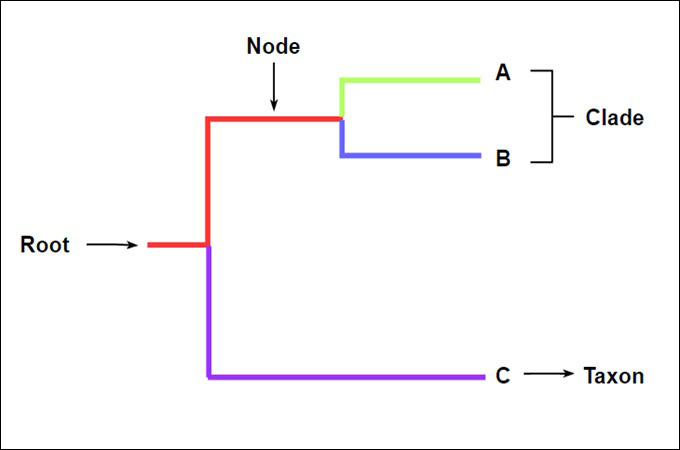

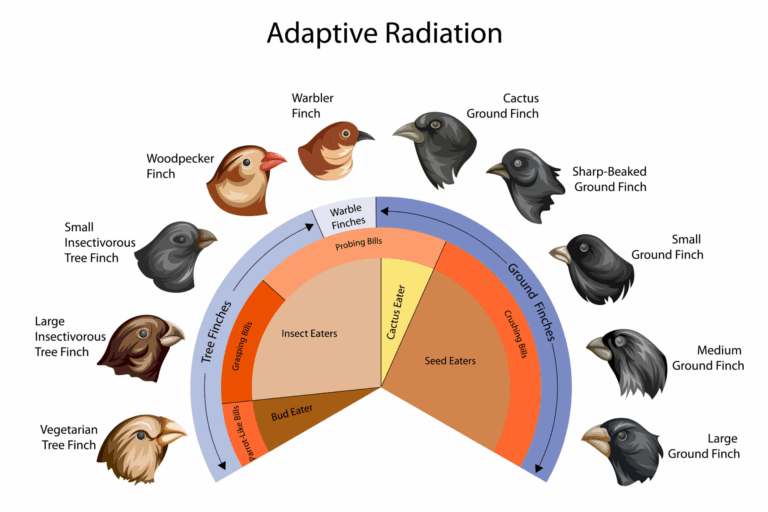

Adaptive radiation is a process where an ancestral species rapidly diversifies into multiple species adapted to different ecological niches. In plants, speciation is often influenced by polyploidy, hybridisation, and environmental variation. Plant adaptive radiation is especially common on islands, in isolated habitats, or following environmental change. The flexibility of plant reproductive systems and their ability to undergo genome duplication allow for rapid formation of reproductively isolated lineages.

📌 Key Features of Adaptive Radiation

- Begins with a single ancestral species colonising new or underused environments.

- Rapid speciation driven by ecological opportunities.

- Morphological and physiological adaptations evolve for specific niches.

- Reduced competition in newly colonised areas accelerates diversification.

- Can occur after mass extinctions or environmental shifts.

- Results in high biodiversity in a relatively short evolutionary period.

🧠 Examiner Tip: When giving examples of adaptive radiation, always link species’ adaptations to the ecological niches they occupy.

📌 Role of Polyploidy in Plant Speciation

- Common in plants but rare in animals.

- Autopolyploidy results from nondisjunction during meiosis, producing unreduced gametes.

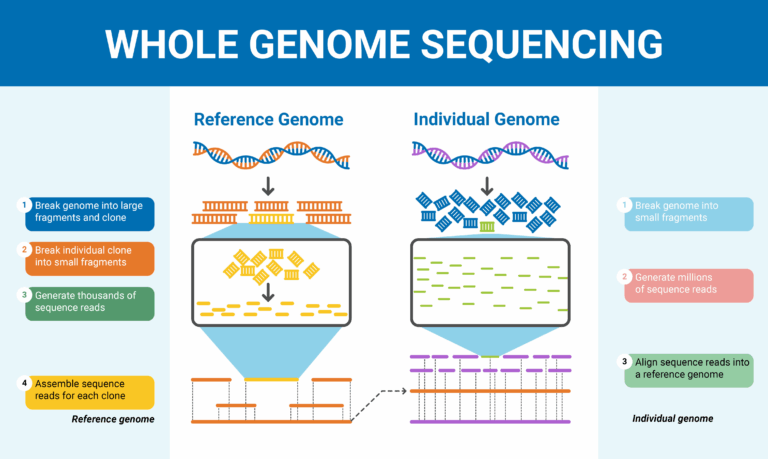

- Allopolyploidy combines chromosome sets from different species.

- Polyploid plants are often reproductively isolated from diploid relatives.

- Can lead to immediate speciation in a single generation.

- Examples: bread wheat (Triticum aestivum), cotton, tobacco.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: An IA could compare chromosome numbers in related plant species to investigate possible polyploid origins.

📌 Environmental and Ecological Drivers

- Island ecosystems promote rapid radiation due to isolation and diverse habitats.

- Mountain ranges create microhabitats and climatic gradients.

- Human-altered landscapes can generate novel niches.

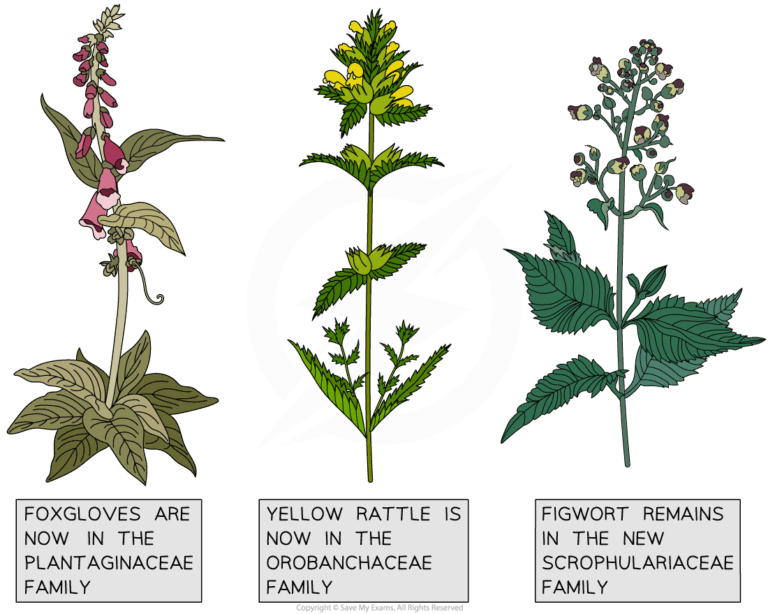

- Pollinator specialisation drives floral diversification.

- Seasonal and climatic variation influences reproductive timing.

- Soil type and nutrient availability affect plant morphology and physiology.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could explore the role of pollinator diversity in driving adaptive radiation in flowering plants.

📌 Examples of Adaptive Radiation in Plants

- Hawaiian silverswords: radiated from a single ancestor into diverse forms adapted to different altitudes and habitats.

- Galápagos Scalesia: tree-like daisies adapting to varied island conditions.

- African violets: diversified in mountain forests with distinct niches.

- Wild sunflowers: adapted to different soil types and moisture levels.

- Brassica crops: artificial selection mimicking natural adaptive diversification.

- Orchid family: extreme floral diversity linked to specialised pollinators.

❤️ CAS Link: A CAS activity could involve planting and observing species adapted to different microhabitats in a school garden to illustrate adaptive variation.

🌍 Real-World Connection:

Understanding adaptive radiation and plant speciation helps in agriculture (developing new crop varieties), conservation (protecting rare endemic plants), and habitat restoration.

📌 Plant Speciation Mechanisms Beyond Polyploidy

- Hybridisation without chromosome doubling can still produce new species.

- Ecological isolation via adaptation to distinct microhabitats.

- Temporal isolation due to differences in flowering periods.

- Gametic incompatibility between pollen and stigma.

- Chromosomal rearrangements reducing fertility with parent species.

- Reinforcement of barriers through selection against hybrids.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Plant speciation challenges the idea that species boundaries are fixed — polyploidy can create new species almost instantly, showing how rapid evolutionary change is possible.