B2.1.1 – MEMBRANE STRUCTURE

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

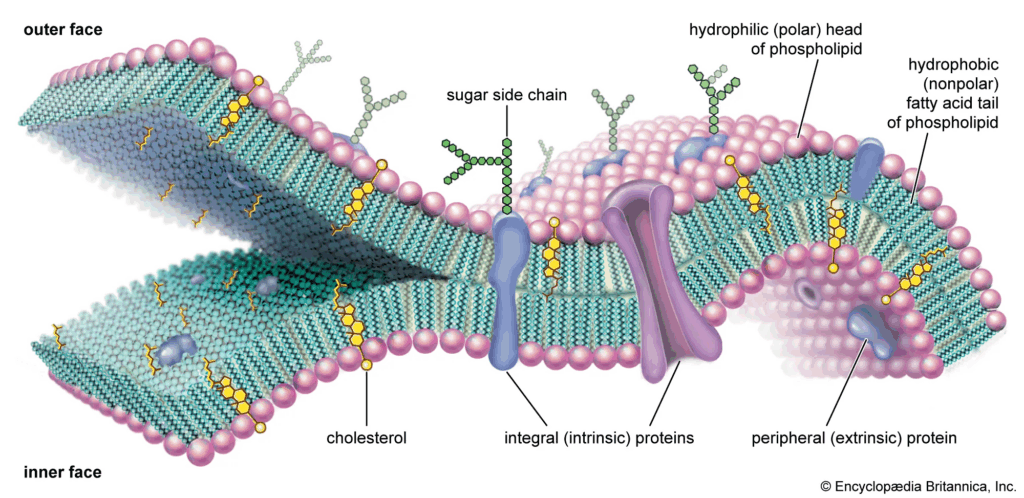

| Phospholipid bilayer | Double layer of phospholipids forming the fundamental structure of membranes, with hydrophilic heads facing outwards and hydrophobic tails facing inwards. |

| Amphipathic | A molecule containing both hydrophilic (water-attracting) and hydrophobic (water-repelling) regions. |

| Fluid mosaic model | Describes membranes as flexible, with lipids and proteins moving laterally while maintaining overall structure. |

| Integral proteins | Proteins embedded within the lipid bilayer, often spanning the membrane. |

| Peripheral proteins | Proteins loosely attached to membrane surfaces or integral proteins, not embedded in the hydrophobic core. |

| Cholesterol | A lipid molecule interspersed within membranes that regulates fluidity and permeability. |

📌Introduction

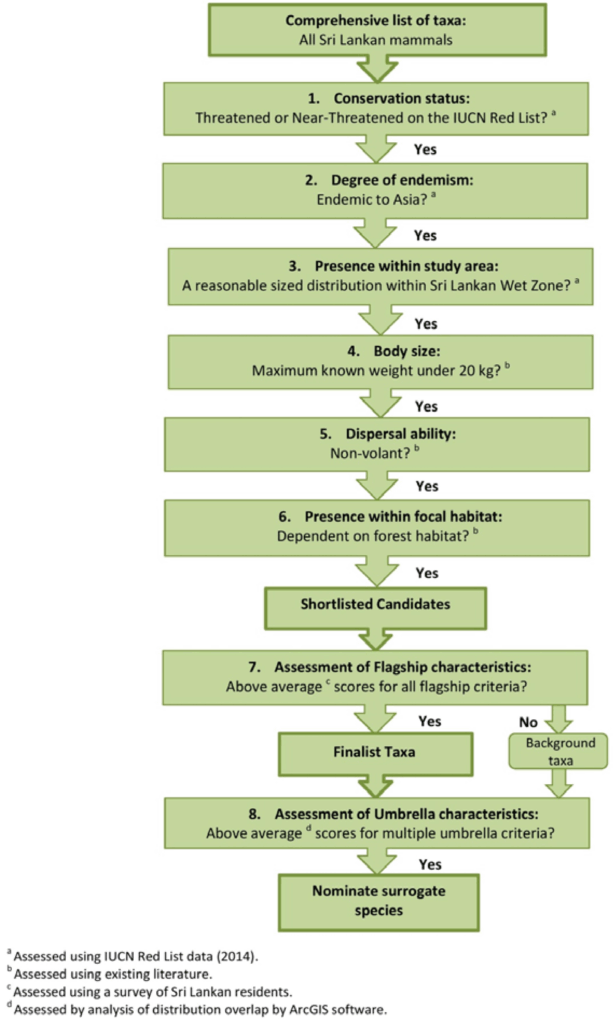

Biological membranes form the boundary between the cell and its environment, and between internal compartments within eukaryotic cells. Their structure ensures selective exchange of materials, compartmentalization, signaling, and energy transduction. The fluid mosaic model, proposed by Singer and Nicolson in 1972, remains the central framework for understanding membrane organization. According to this model, membranes are dynamic, with proteins “floating” in a sea of phospholipids, giving them both flexibility and specificity. The interplay between lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates results in membranes that are not merely passive barriers but active regulators of cellular life.

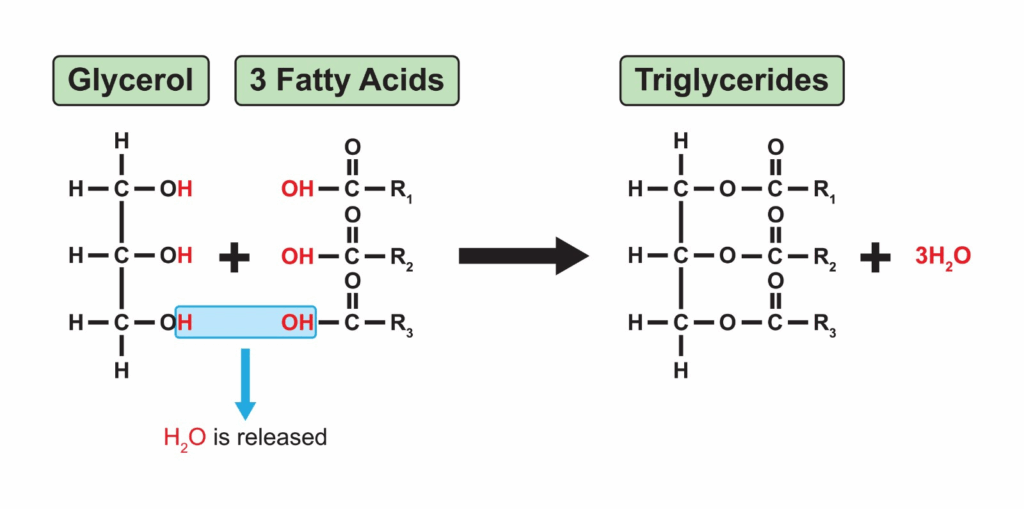

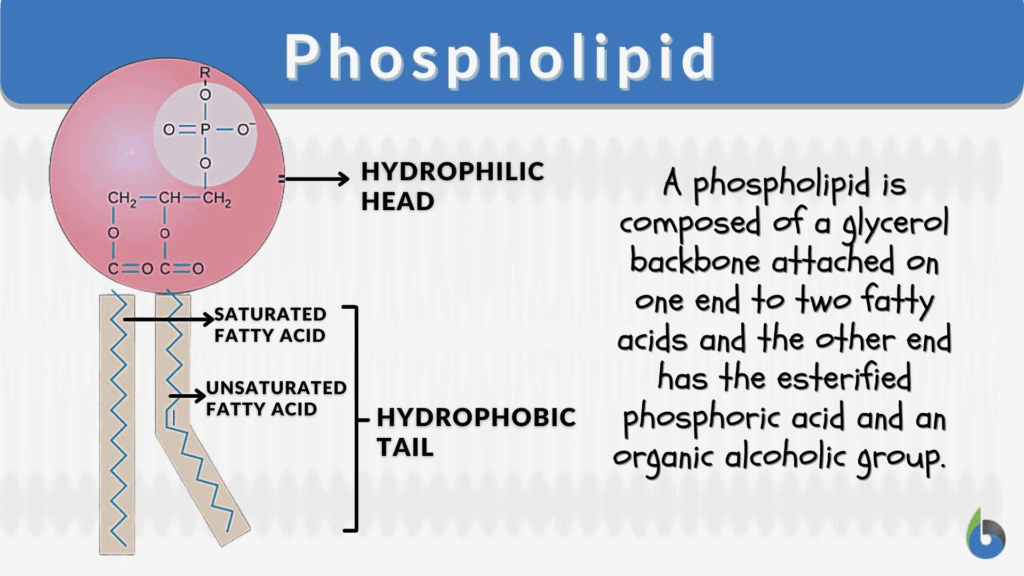

📌 Phospholipids and Amphipathic Nature

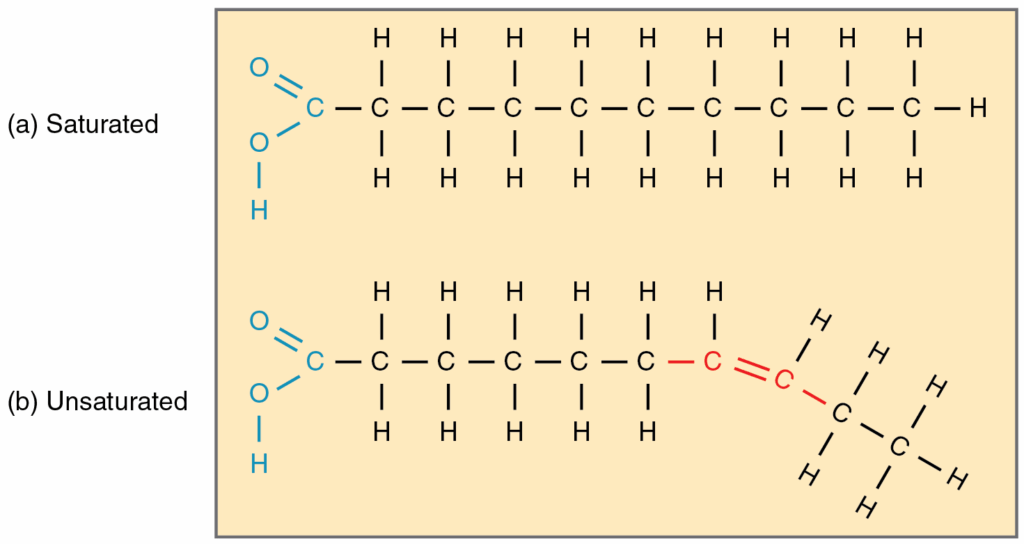

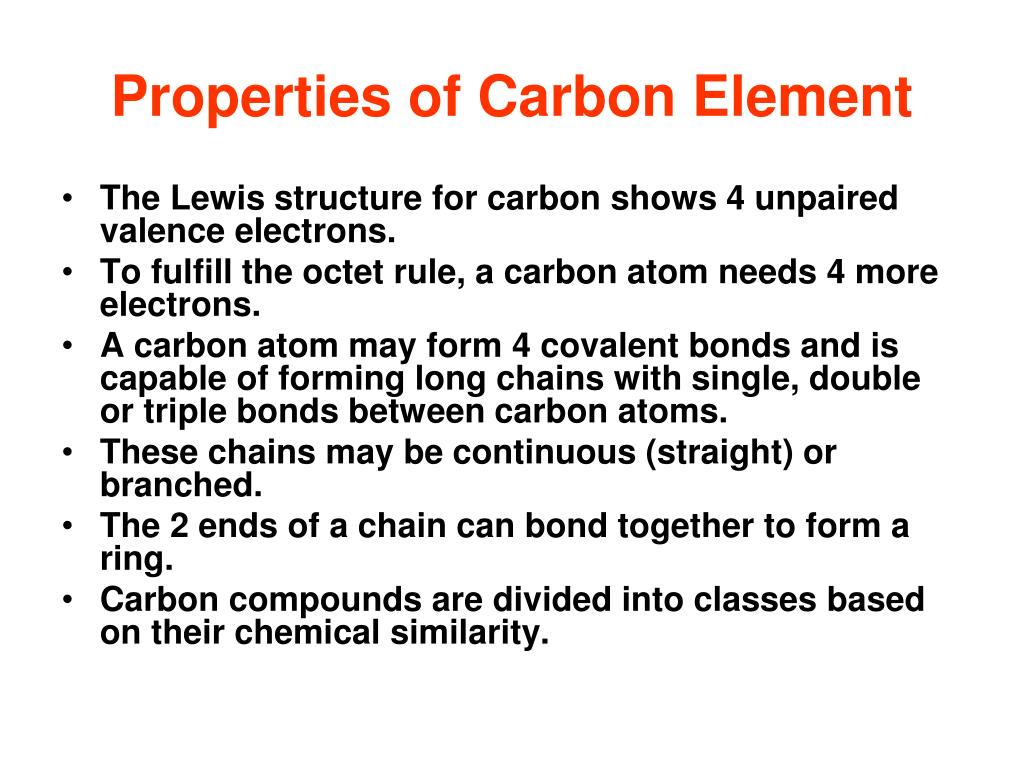

- Phospholipids are amphipathic molecules with a hydrophilic phosphate head and hydrophobic fatty acid tails.

- In aqueous environments, phospholipids self-assemble into bilayers, with heads facing water and tails shielded inside.

- This bilayer arrangement produces a hydrophobic core, preventing free passage of polar molecules and ions.

- The amphipathic nature underpins selective permeability — small, non-polar molecules diffuse easily, while charged or large molecules require transport proteins.

🧠 Examiner Tip: When drawing the bilayer, always show hydrophilic heads facing outwards toward aqueous environments and hydrophobic tails inwards. Label integral vs peripheral proteins clearly, as this is a common diagram question.

📌 Membrane Proteins and the Fluid Mosaic Model

- Integral proteins penetrate the hydrophobic core; some span the bilayer (transmembrane proteins). They function as channels, carriers, pumps, or receptors.

- Peripheral proteins attach loosely to surfaces, playing roles in signaling and anchoring.

- Membranes are described as “fluid” because phospholipids and proteins move laterally, allowing flexibility, endocytosis, and dynamic interactions.

- They are “mosaics” because of the irregular distribution of proteins, glycoproteins, and glycolipids scattered across the bilayer.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Osmosis experiments using dialysis tubing (as an artificial membrane) can illustrate selective permeability. More advanced setups include investigating the effect of detergents or alcohol on beetroot cell membranes by measuring pigment leakage.

📌 Cholesterol and Membrane Stability

- Cholesterol inserts between phospholipids, affecting fluidity and permeability.

- At low temperatures, it prevents phospholipids from packing too tightly, maintaining flexibility.

- At high temperatures, it holds fatty acid tails together, preventing excessive fluidity and leakage.

- Cholesterol reduces permeability to small water-soluble molecules, stabilizing the bilayer.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how membrane fluidity changes with lipid composition — e.g., the role of unsaturated fatty acids in cold-adapted organisms. Another route is analyzing how drugs or alcohol disrupt membrane permeability in model systems.

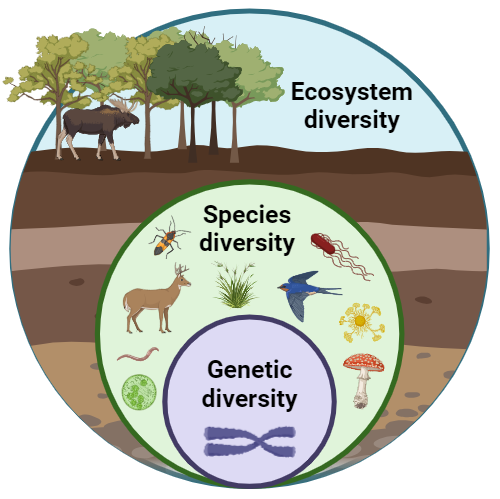

📌 Specialized Membrane Components

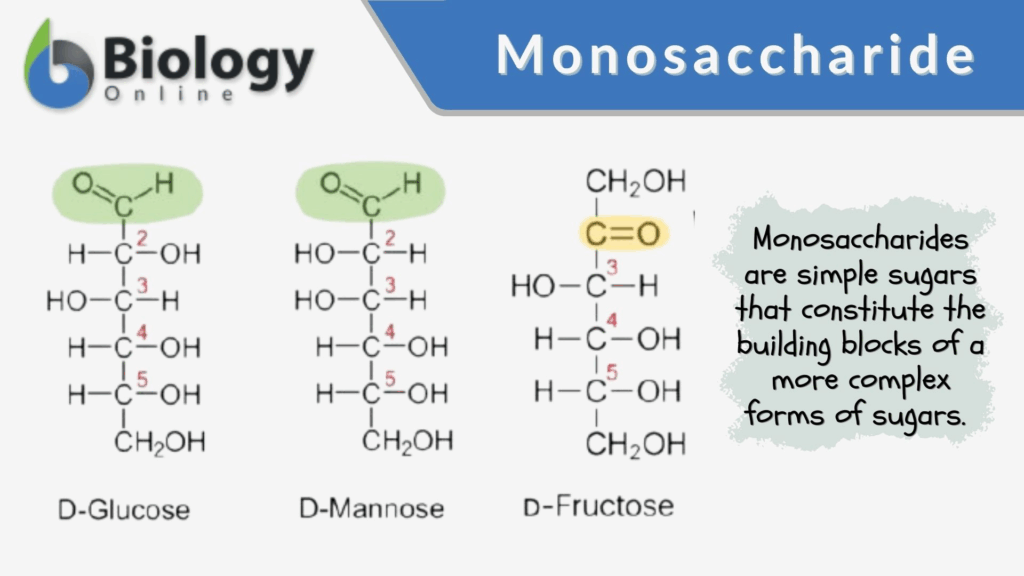

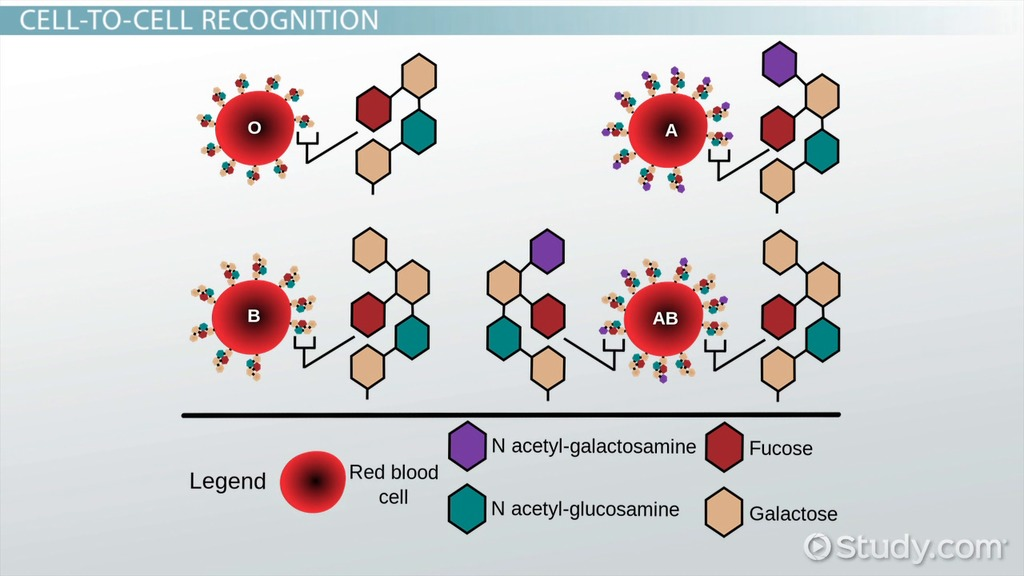

- Glycoproteins and glycolipids extend from the cell surface, serving as receptors and recognition markers (e.g., blood group antigens).

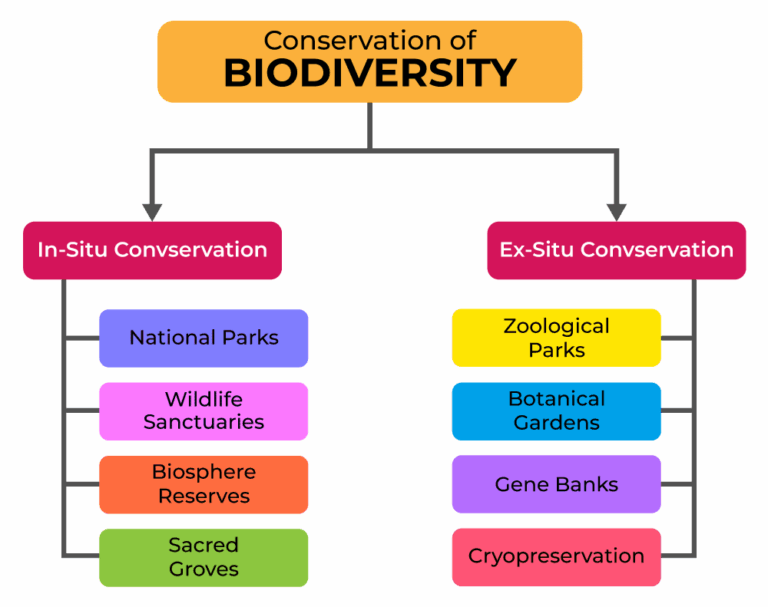

- These molecules mediate cell-cell communication, immune recognition, and adhesion.

- Specialized domains such as lipid rafts concentrate signaling molecules, showing that membranes are not uniform but compartmentalized within themselves.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could create interactive models showing how detergents, alcohol, or temperature changes affect membrane permeability, linking classroom biology to public health campaigns on alcohol effects or frostbite.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Membrane structure underlies critical processes such as nerve transmission (via ion channels), hormone signaling (via receptors), and immunity (via glycoprotein recognition). Drugs often target membrane proteins — e.g., antihistamines block histamine receptors. Understanding membrane structure also enables biotechnology applications like liposome-based drug delivery.

📌 Applications of Membrane Structure

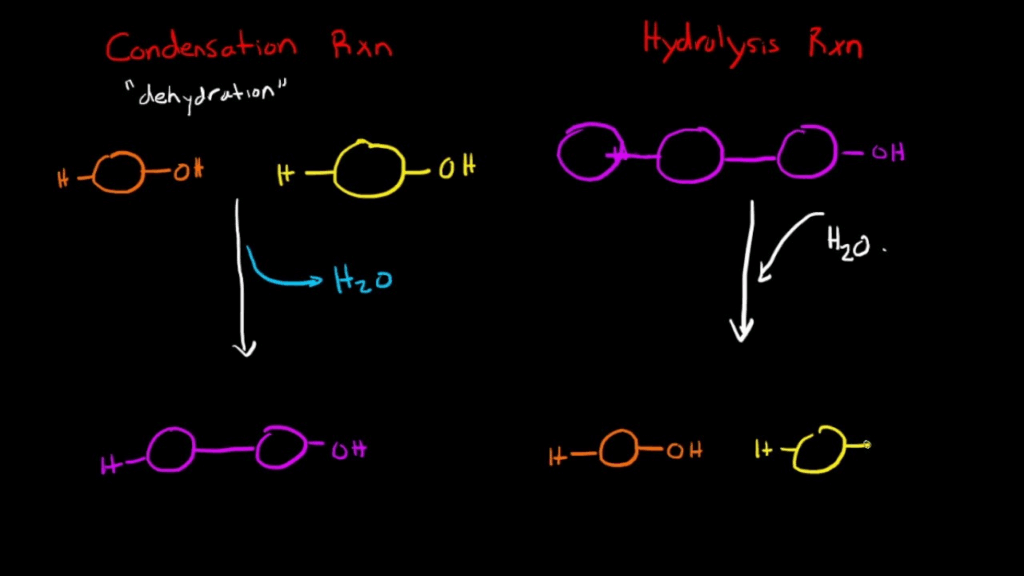

- Explains how endocytosis and exocytosis transport large molecules.

- Provides the framework for selective transport, signaling pathways, and compartmentalization.

- Variations in lipid and protein composition reflect cell specialization — e.g., myelin membranes are rich in lipids for insulation.

🔍 TOK Perspective: The fluid mosaic model is itself a scientific model — a simplification of reality. TOK reflection: How reliable are models in explaining dynamic biological systems, and what happens when evidence requires us to revise them?