B3.1.2 – GAS EXCHANGE IN COMPLEX ANIMALS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Respiratory surface | A specialised surface adapted for efficient exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. |

| Gills | Highly vascularised respiratory surfaces in aquatic animals, specialised for extracting dissolved oxygen. |

| Tracheal system | A system of air-filled tubes in insects that deliver oxygen directly to tissues. |

| Lungs | Internal respiratory organs in terrestrial animals adapted for gas exchange with air. |

| Countercurrent exchange | A mechanism in gills where water and blood flow in opposite directions, maximising oxygen uptake. |

📌Introduction

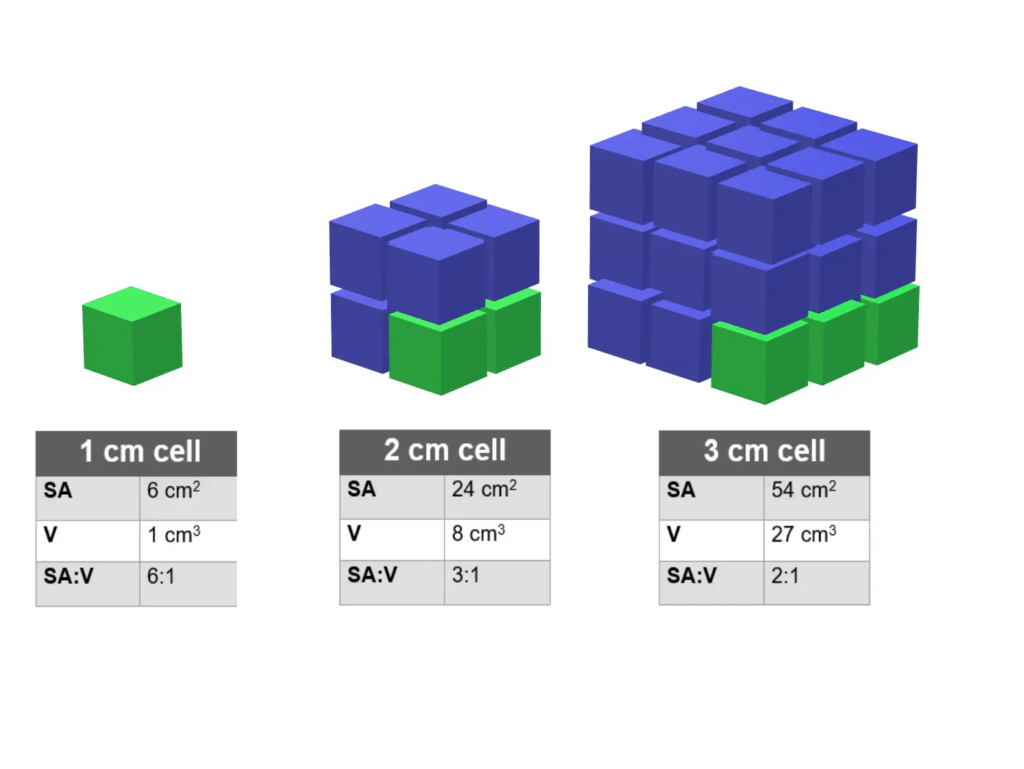

Complex animals cannot rely on diffusion alone for gas exchange due to their larger body size, lower SA:V ratios, and higher metabolic demands. They require specialised respiratory surfaces and circulatory systems to deliver oxygen efficiently and remove carbon dioxide. Adaptations include gills in fish, tracheal systems in insects, and lungs in mammals. Each system balances efficiency, water conservation, and environmental constraints.

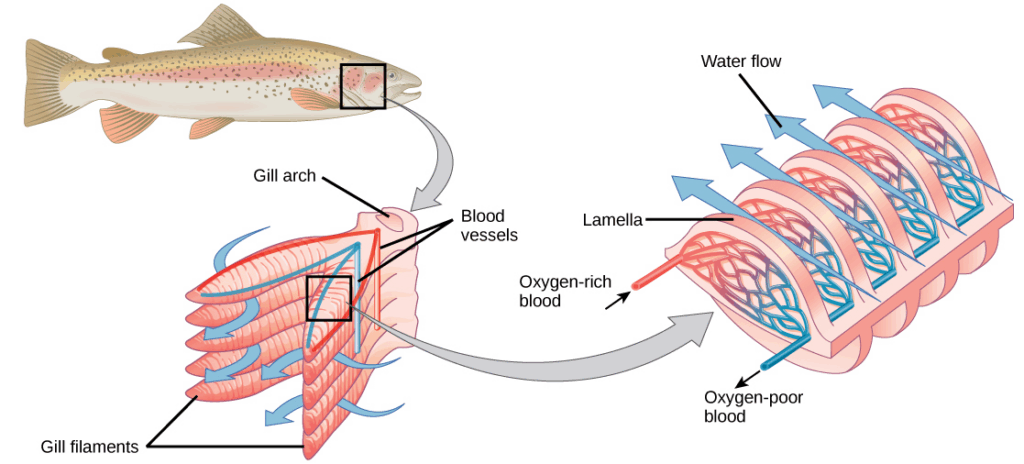

📌 Gas Exchange in Fish (Gills)

- Gills are highly folded, thin, and richly supplied with capillaries, providing a large surface area for gas exchange.

- The countercurrent exchange system maintains a steep concentration gradient: water flows across gill lamellae in the opposite direction to blood flow, maximising oxygen uptake.

- Gills are adapted for aquatic environments where oxygen is less abundant than in air.

- Ventilation is maintained by buccal pumping, drawing water continuously over the gill surfaces.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always mention countercurrent flow when describing fish gills. Answers that only state “water passes over gills” are incomplete.

📌 Gas Exchange in Insects (Tracheal System)

- Insects use a tracheal system where air enters through spiracles and diffuses along tracheae and tracheoles directly to tissues.

- Tracheoles reach individual cells, reducing diffusion distance.

- Ventilation is aided by rhythmic body movements that pump air in and out of the tracheae.

- The tracheal system avoids reliance on blood for oxygen transport, making it highly efficient for small terrestrial animals.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could design investigations into insect spiracle activity, such as observing spiracle opening in response to varying CO₂ concentrations, linking behaviour to efficiency of gas exchange.

📌 Gas Exchange in Mammals (Lungs)

- Mammalian lungs are internal, minimising water loss while allowing efficient gas exchange in a terrestrial environment.

- The alveoli provide a vast surface area, thin walls, and are surrounded by capillaries, ensuring short diffusion distances and efficient exchange.

- Surfactant reduces surface tension, preventing alveolar collapse.

- Oxygen diffuses into red blood cells, binding to haemoglobin for transport, while carbon dioxide diffuses out.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how environmental conditions shape respiratory adaptations — for example, comparing fish gill efficiency to mammalian lungs, or examining adaptations in high-altitude animals.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could create an educational video comparing respiratory systems across species, then share it with peers or schools to illustrate biological diversity.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Understanding gas exchange adaptations informs aquaculture (optimising oxygen in fish farming), pest control (targeting insect spiracle activity), and human medicine (treating lung diseases like emphysema).

📌 Comparison of Systems

- Gills, tracheae, and lungs all maximise surface area, minimise diffusion distance, and maintain concentration gradients.

- However, strategies differ: fish rely on countercurrent flow, insects use direct diffusion without blood, and mammals use circulatory transport.

- These systems demonstrate convergent principles of efficiency despite structural differences.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Gas exchange systems illustrate how organisms evolve different solutions to the same problem — supplying oxygen. TOK questions arise about analogy in science: to what extent can different systems be compared as models of the same principle?