B4.1.3 –ADAPTATIONS FOR LOW OXYGEN AND SPECIALISED ENVIRONMENTS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Hypoxia | A condition where tissues receive insufficient oxygen. |

| Myoglobin | An oxygen-binding protein in muscles that stores oxygen for use during low supply. |

| Haemoglobin affinity | The tendency of haemoglobin to bind oxygen, which can shift depending on species or environment. |

| Anaerobic respiration | Energy production in the absence of oxygen, less efficient but essential during oxygen scarcity. |

| High-altitude adaptation | Physiological and genetic traits that enhance oxygen uptake and transport in low-oxygen environments. |

| Symbiosis | A biological relationship, often mutualistic, that can help organisms survive in specialised habitats. |

📌Introduction

Oxygen is vital for aerobic metabolism, but many environments present limited availability — high altitudes, deep oceans, stagnant waters, or subterranean burrows. Organisms in such conditions have evolved strategies to increase oxygen uptake, store oxygen for later use, or survive with minimal oxygen. These include respiratory protein modifications, circulatory adjustments, metabolic suppression, and behavioural strategies. Adaptations allow species to colonise niches inaccessible to competitors, contributing to ecological diversity.

📌 High-Altitude Adaptations

- Animals at altitude face reduced partial pressure of oxygen, lowering diffusion into blood.

- Adaptations include:

- Increased haemoglobin affinity for oxygen (e.g., llamas, yaks).

- Higher lung surface area and ventilation rates.

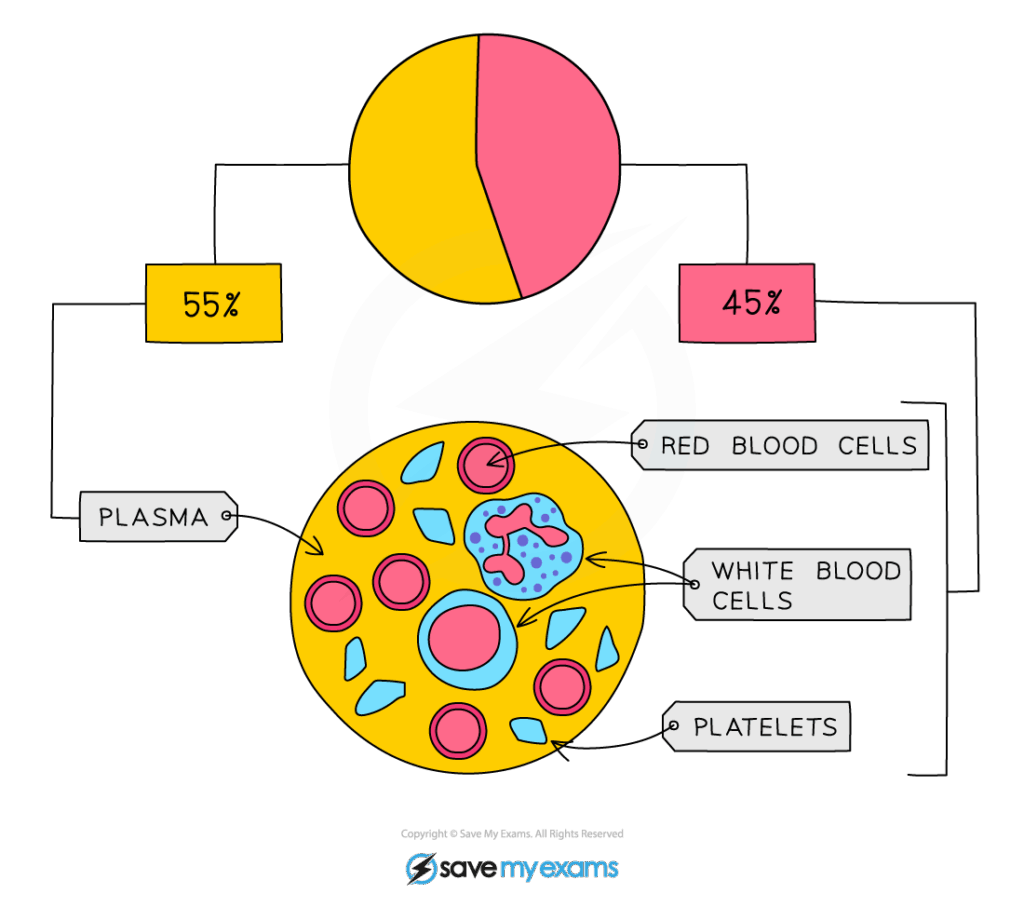

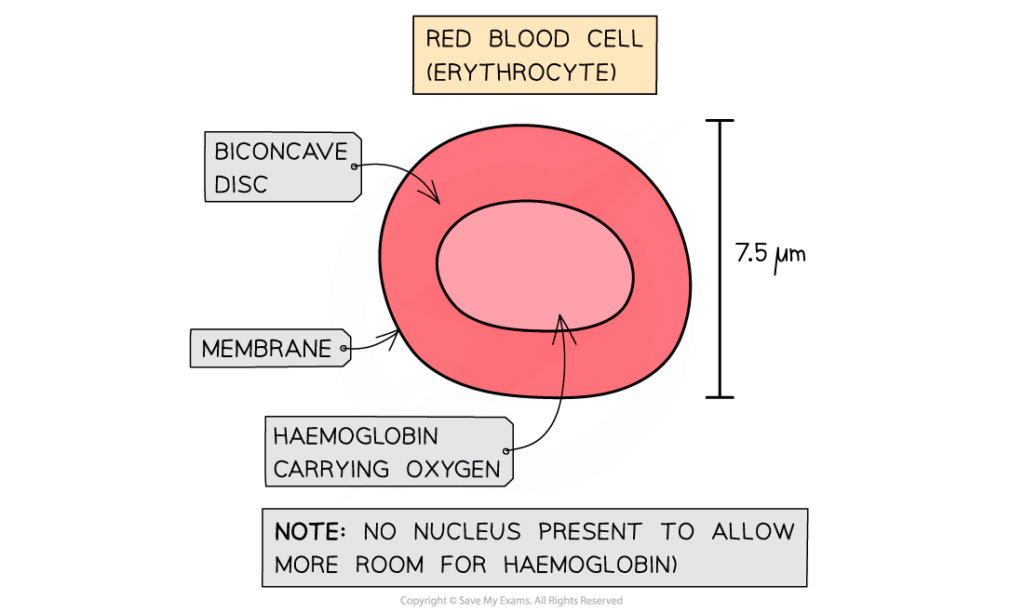

- Enlarged chest cavities and higher red blood cell counts.

- Humans acclimatise temporarily by increasing erythropoietin (EPO) production, boosting red blood cell numbers.

- Indigenous populations (e.g., Tibetans, Andeans) show genetic adaptations such as altered haemoglobin genes or improved oxygen utilisation in tissues.

🧠 Examiner Tip: For altitude questions, don’t only mention “more red blood cells.” Add details like haemoglobin affinity or lung capacity for higher marks.

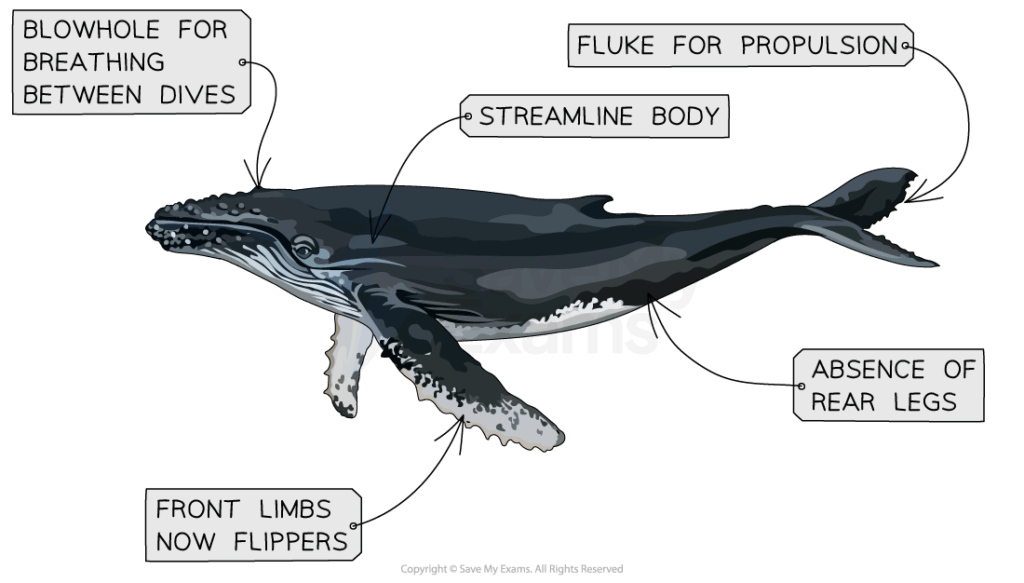

📌 Diving Mammals

- Marine mammals (whales, seals) tolerate long dives by:

- Storing oxygen in large blood volumes and myoglobin-rich muscles.

- Slowing heart rate (bradycardia) to conserve oxygen.

- Redirecting blood flow to vital organs.

- Anaerobic respiration is used in extended dives, with lactic acid buildup managed upon resurfacing.

- Collapsible lungs prevent nitrogen narcosis and decompression sickness.

- Some species dive for hours (sperm whales) due to extreme myoglobin concentrations.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could simulate oxygen dissociation curves for high-affinity hemoglobin’s vs normal, or investigate effects of exercise on oxygen saturation using digital sensors.

📌 Burrowing and Underground Organisms

- Animals in subterranean habitats (e.g., moles, naked mole rats) encounter hypoxic and hypercapnic conditions.

- Adaptations include:

- Lower metabolic rates to conserve oxygen.

- Higher tolerance to CO₂ and acidic conditions.

- Haemoglobin with increased oxygen affinity.

- Naked mole rats survive prolonged oxygen deprivation by switching to fructose-based anaerobic pathways.

- Burrow ventilation behaviours (e.g., communal digging) help refresh air supply.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could compare high-altitude and subterranean adaptations, asking whether genetic changes (e.g., haemoglobin mutations) or behavioural strategies play a larger role in survival.

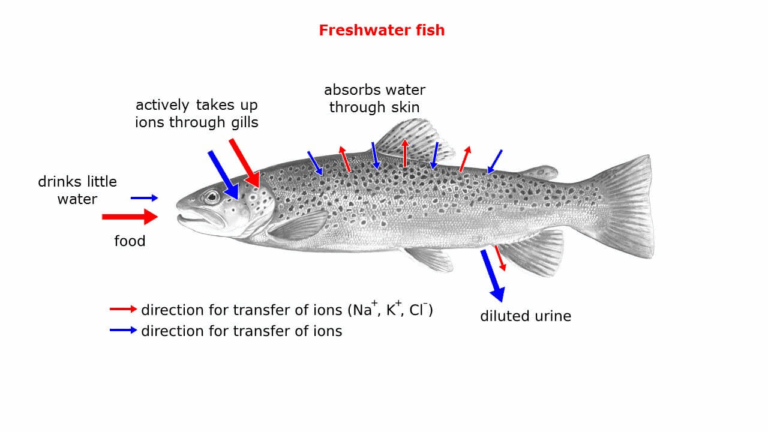

📌 Aquatic and Hypoxic Water Adaptations

- Fish in oxygen-poor waters (e.g., swamps, stagnant ponds) show adaptations such as:

- Accessory respiratory organs (labyrinth organ in bettas).

- Air-breathing behaviours (gulping air).

- Thin gill lamellae for improved oxygen diffusion.

- Amphibians (frogs) supplement lung breathing with cutaneous gas exchange.

- Some fish and amphibians enter metabolic depression during hypoxia, reducing energy needs.

- Turtles can overwinter under ice using anaerobic metabolism and buffering lactic acid with calcium carbonate in shells.

❤️ CAS Link: A CAS project could involve building educational displays on “How animals survive without oxygen” for schools or museums, linking biology with environmental awareness.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Research into hypoxia tolerance has medical relevance — insights from naked mole rats inform stroke research, and diving mammals inspire safer anaesthesia and decompression practices.

📌 Extreme Symbiotic and Evolutionary Strategies

- Hydrothermal vent organisms survive in oxygen-poor, sulphide-rich waters by symbiosis with chemosynthetic bacteria.

- Some invertebrates use haemocyanin (copper-based pigment) instead of haemoglobin, adapted for low-oxygen binding.

- Certain parasites survive in host intestines by tolerating anaerobic conditions.

- Facultative anaerobes switch between aerobic and anaerobic respiration depending on oxygen availability.

- Evolutionary innovations such as tracheal gills in aquatic insect larvae expand niches in hypoxic habitats.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Low-oxygen adaptations show how biology blurs reductionist and holistic views — we model oxygen uptake with dissociation curves, yet survival depends on integrated systems (behaviour, anatomy, metabolism). TOK question: how far can simplified models capture the reality of extreme survival?ironment, hormones, and behaviour, or do they risk oversimplification?