C1.3.1 LIGHT-DEPENDENT REACTIONS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

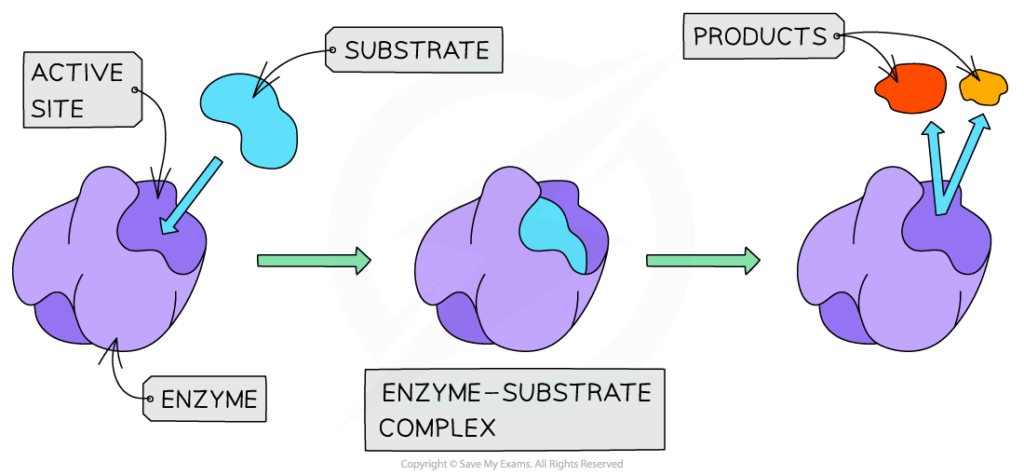

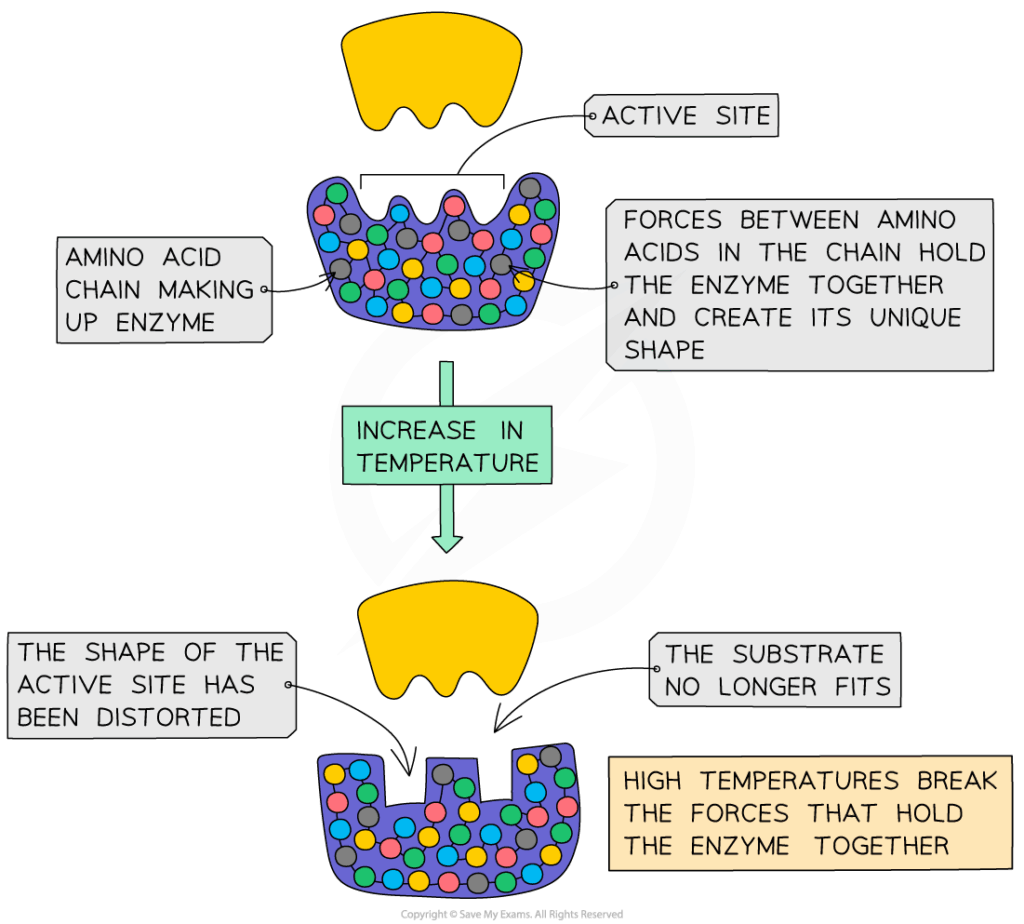

| Photosystem | Protein–pigment complex in the thylakoid membrane that absorbs light and initiates electron flow. |

| Photolysis | Splitting of water by light energy into protons (H⁺), electrons, and oxygen. |

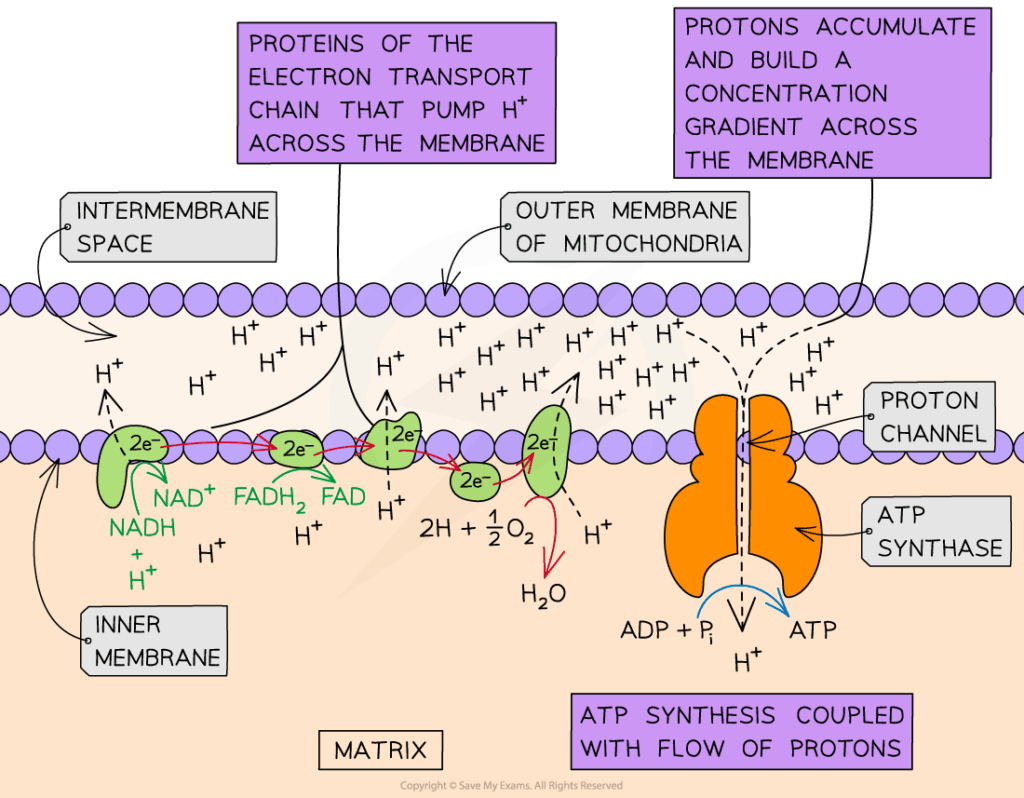

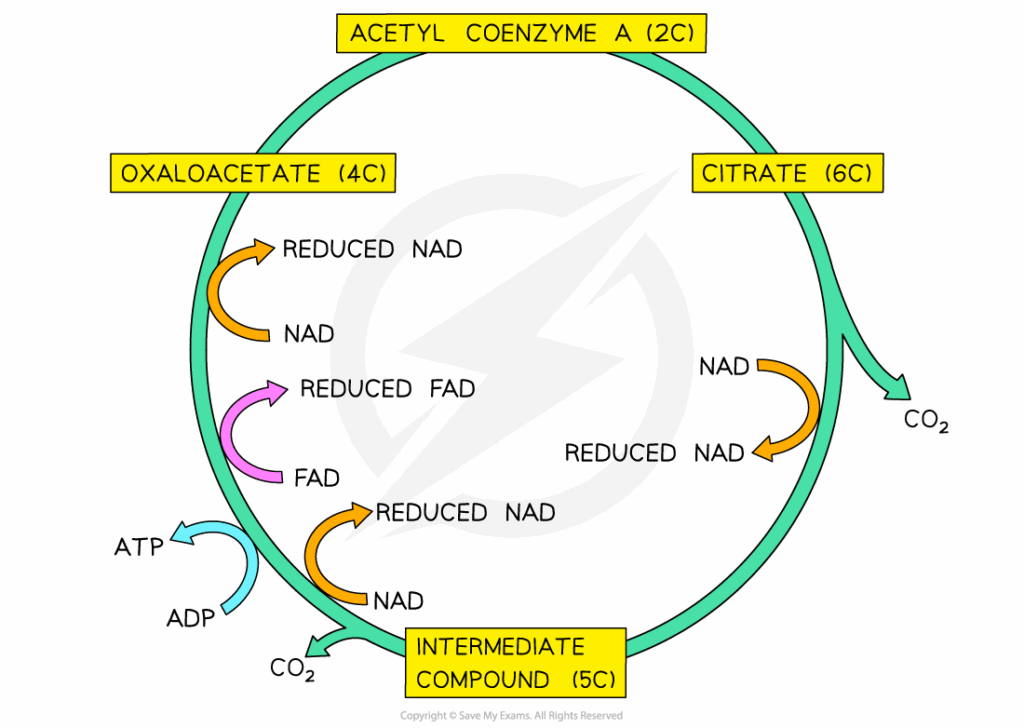

| Electron transport chain (ETC) | Series of carriers in the thylakoid membrane transferring electrons, releasing energy for proton pumping. |

| Chemiosmosis | Movement of protons down their electrochemical gradient through ATP synthase, generating ATP. |

| NADP⁺ / NADPH | Final electron acceptor in the light-dependent reaction; NADPH carries reducing power to the Calvin cycle. |

| Photophosphorylation | Light-driven synthesis of ATP in chloroplasts. |

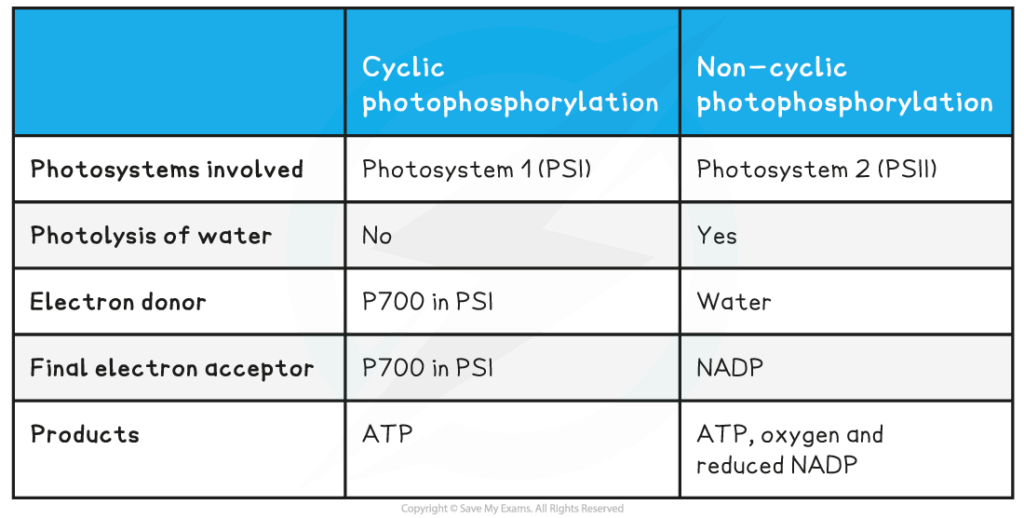

| Cyclic photophosphorylation | Electron flow involving only PSI, generating ATP but not NADPH or oxygen. |

📌Introduction

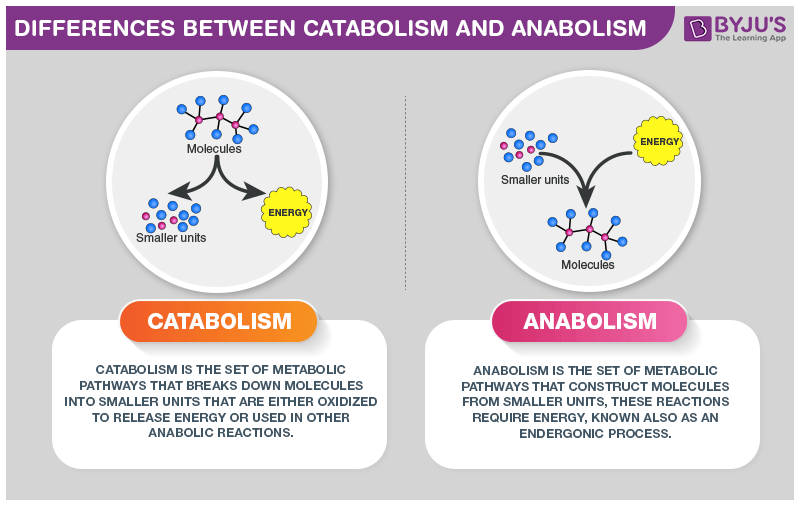

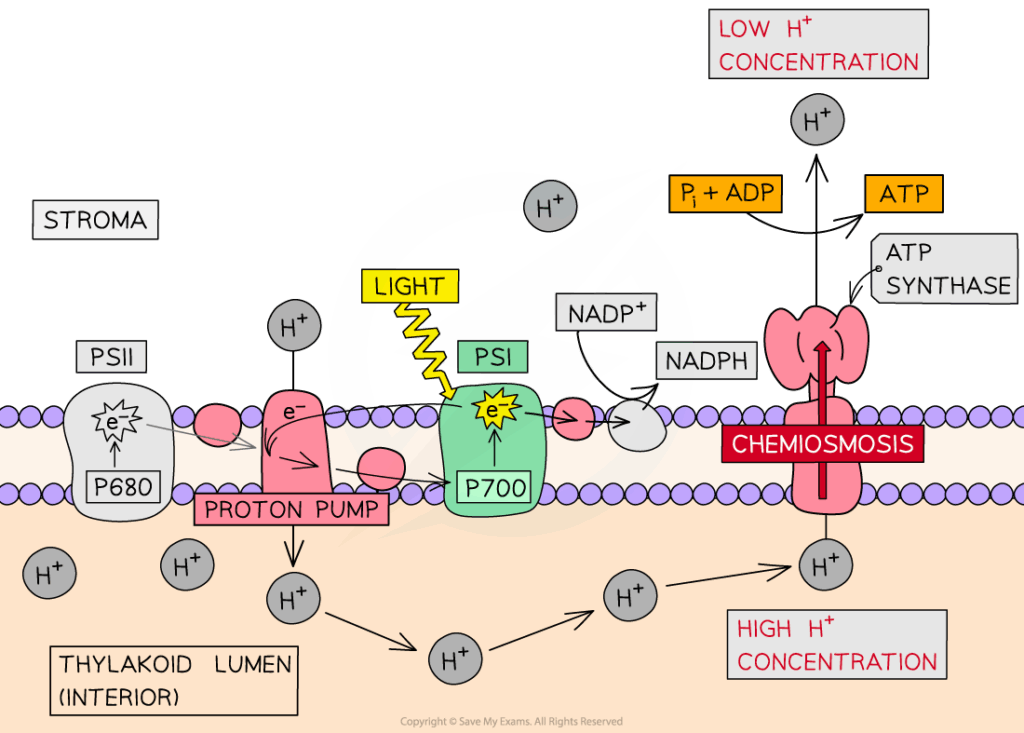

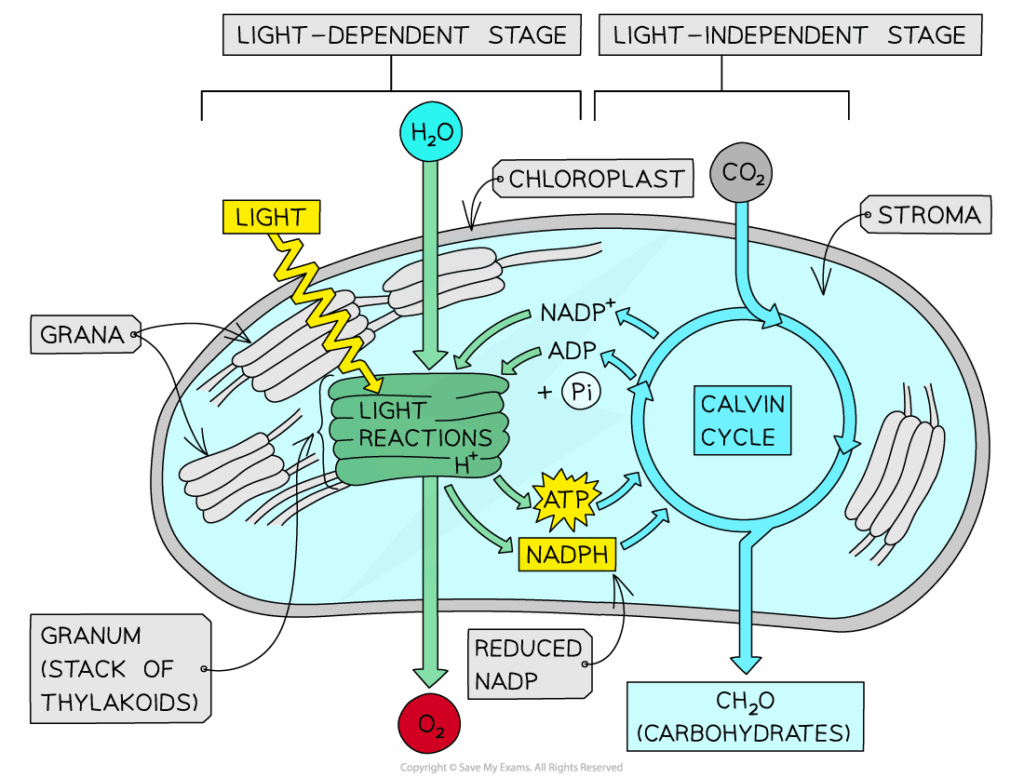

The light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis occur in the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts and capture light energy to produce ATP and NADPH, which power the Calvin cycle. These reactions also generate oxygen as a byproduct from the splitting of water. Two photosystems (PSII and PSI) work together to drive electron flow, enabling the conversion of solar energy into chemical energy.

📌 Steps of Non-Cyclic Photophosphorylation

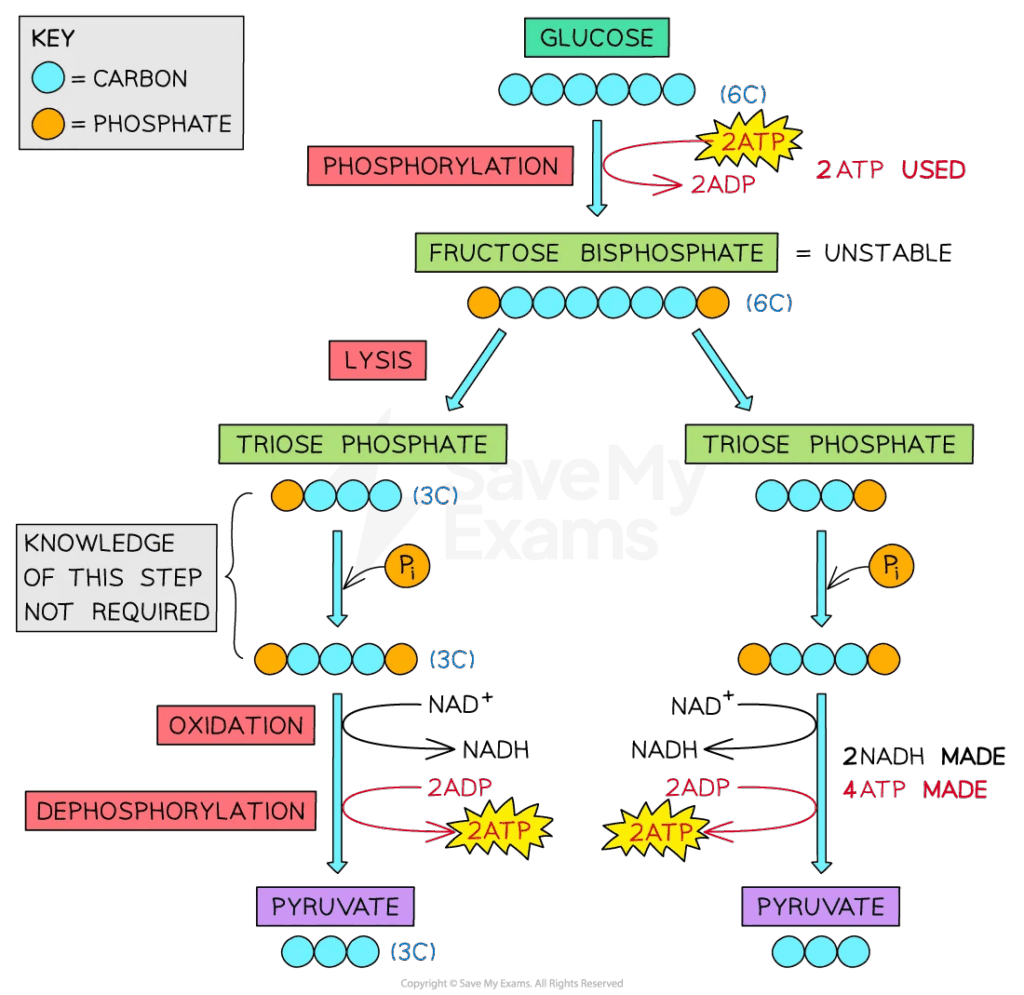

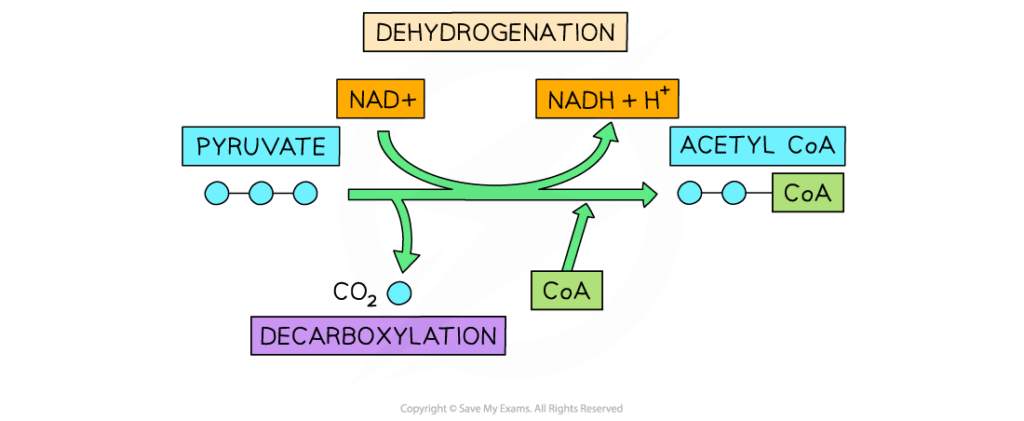

- Photosystem II (PSII) absorbs photons → energizes electrons in chlorophyll a.

- Energized electrons pass down the electron transport chain, driving proton pumping into the thylakoid lumen.

- Lost electrons from PSII are replaced by photolysis of water:

- H₂O → 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ + ½O₂.

- Electrons reach Photosystem I (PSI), are re-excited by light, and transferred to NADP⁺ reductase, reducing NADP⁺ → NADPH.

- Proton gradient drives ATP synthase to produce ATP via chemiosmosis.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always state that photolysis occurs at PSII, not PSI. Many students confuse the roles of the two photosystems.

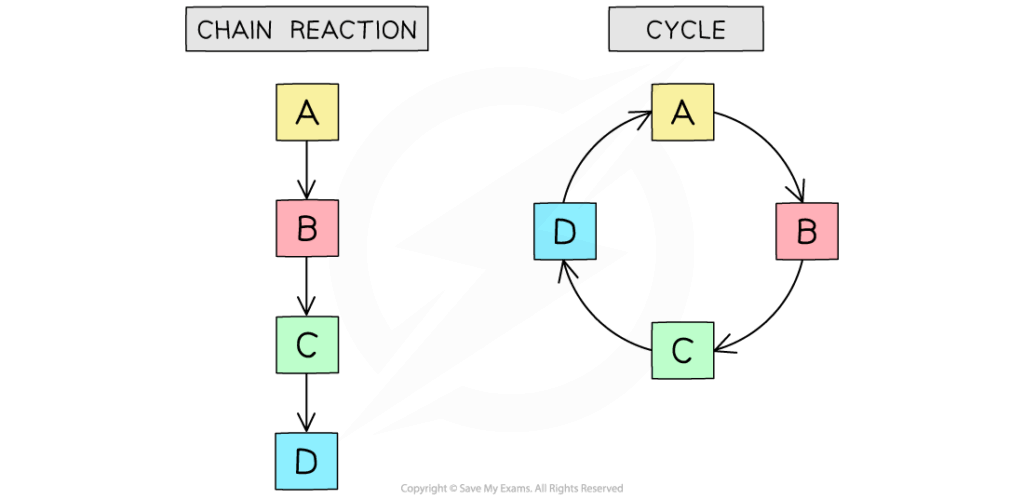

📌 Cyclic Photophosphorylation

- Involves only PSI.

- Electrons cycle back from ferredoxin to the ETC instead of reducing NADP⁺.

- Produces ATP only (no NADPH, no O₂).

- Provides extra ATP needed for the Calvin cycle when demand exceeds NADPH.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could test the effect of different light wavelengths on photosynthesis using a colorimeter and leaf discs, linking results to the role of pigments in light absorption.

📌 Outputs of the Light-Dependent Reaction

- ATP (for Calvin cycle).

- NADPH (for reduction reactions in Calvin cycle).

- O₂ (released as a byproduct of photolysis).

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate the relative contribution of cyclic vs non-cyclic photophosphorylation under stress conditions (e.g., high light intensity, drought).

📌 Role of Thylakoid Structure

- Large surface area of thylakoid membranes accommodates many photosystems and ETC proteins.

- Thylakoid lumen provides a confined space for rapid proton accumulation.

- ATP synthase complexes are embedded in membranes, coupling chemiosmosis to ATP synthesis.

- Grana maximize efficiency of light capture.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design solar panel experiments modeling how light capture and conversion in chloroplasts inspire renewable energy technologies.

🌍 Real-World Connection: The light-dependent reactions provide the oxygen essential for aerobic life. Artificial photosynthesis research mimics these processes to produce clean fuels like hydrogen. In agriculture, LED lighting tailored to specific wavelengths optimizes crop photosynthesis in greenhouses.

📌 Integration with Photosynthesis

- Light-dependent reactions supply ATP and NADPH required for carbon fixation in the Calvin cycle.

- Rate of Calvin cycle is directly dependent on light-dependent reaction outputs.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Light reactions are modeled using biochemical pathways and spectroscopy. TOK reflection: To what extent can models of invisible processes, like electron flow in thylakoids, be considered reliable knowledge?