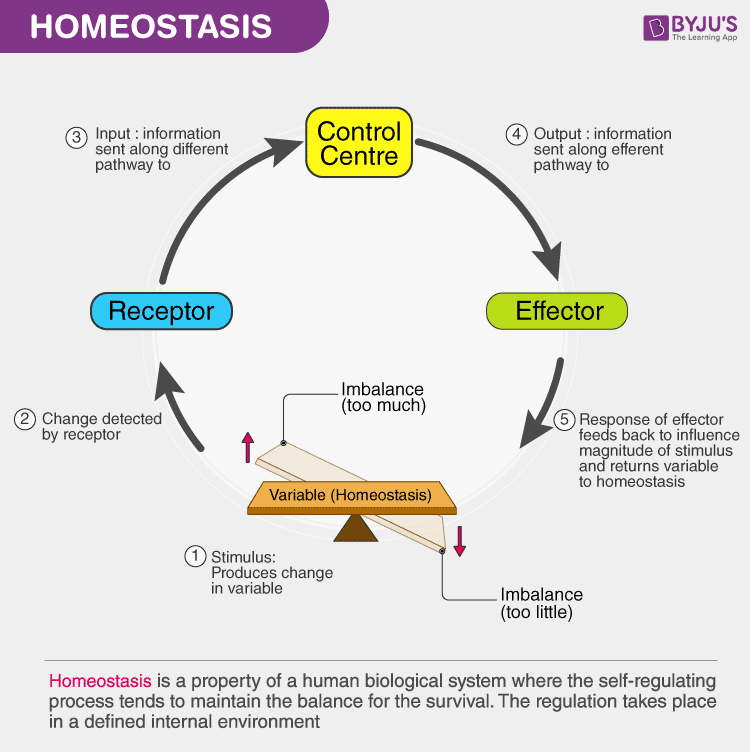

C3.1.2 HOMEOSTASIS MECHANISMS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Homeostasis | The maintenance of a stable internal environment despite external fluctuations. |

| Negative feedback | A control mechanism that counteracts changes, restoring conditions to a set point. |

| Positive feedback | A mechanism that amplifies changes, moving conditions away from a set point. |

| Effector | An organ, tissue, or cell that brings about a response to restore balance. |

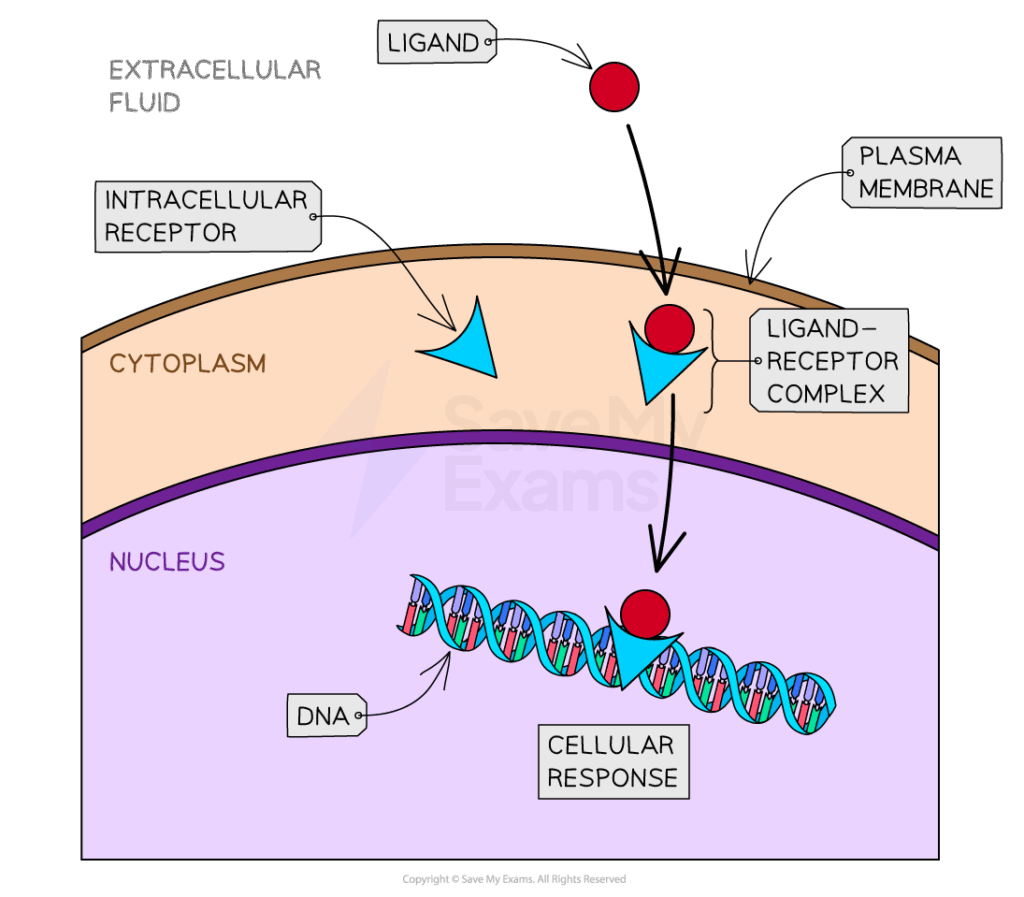

| Receptor | A sensor that detects internal or external changes (stimuli). |

| Set point | The optimal level at which a physiological condition is maintained (e.g., 37 °C for human body temperature). |

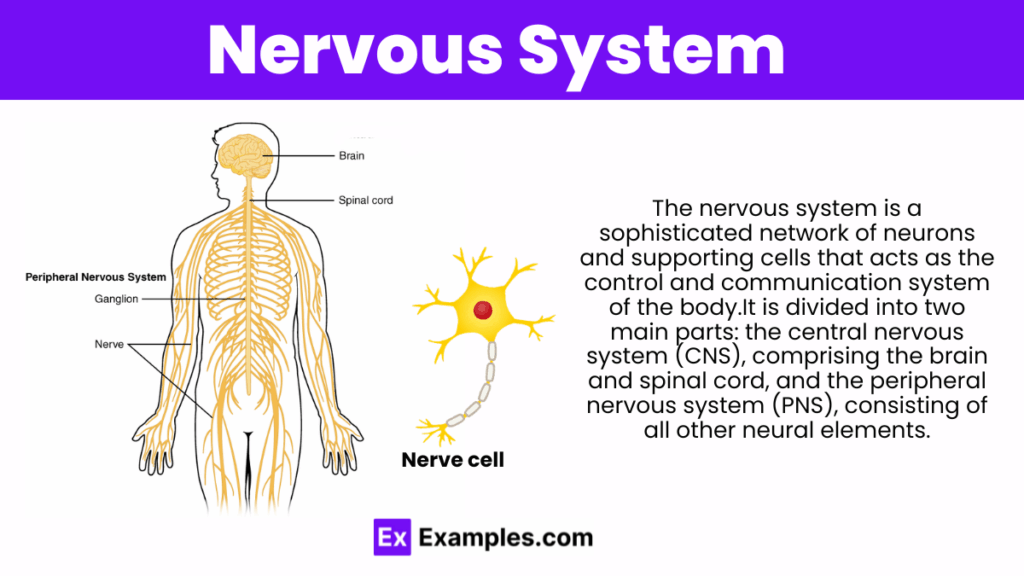

📌Introduction

Homeostasis is the foundation of physiological stability in living organisms. It ensures that key conditions such as temperature, pH, blood glucose, and water balance remain within narrow limits to allow enzymes and cellular processes to function optimally. Homeostasis is achieved through feedback mechanisms that involve continuous monitoring, comparison to a set point, and responses from effectors. While negative feedback stabilises systems, positive feedback temporarily amplifies responses, often in special processes like childbirth. Disruptions in homeostasis can lead to disease and reduced survival, highlighting its essential role in biology.

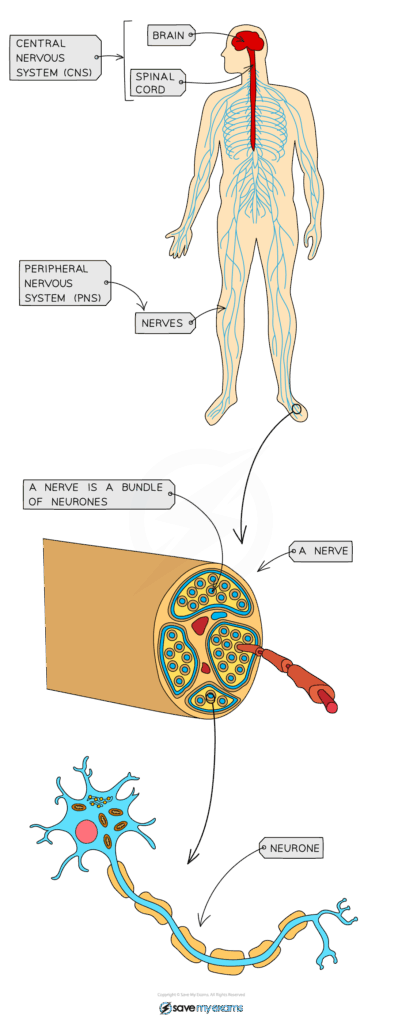

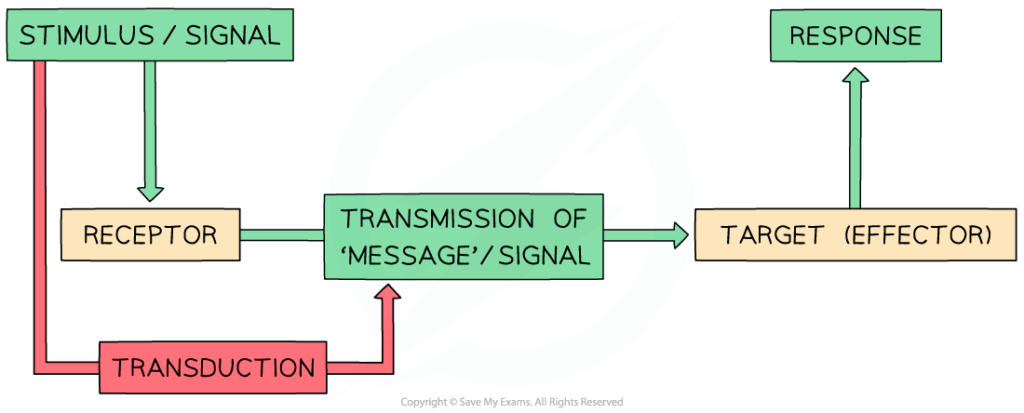

📌 Components of Homeostatic Control Systems

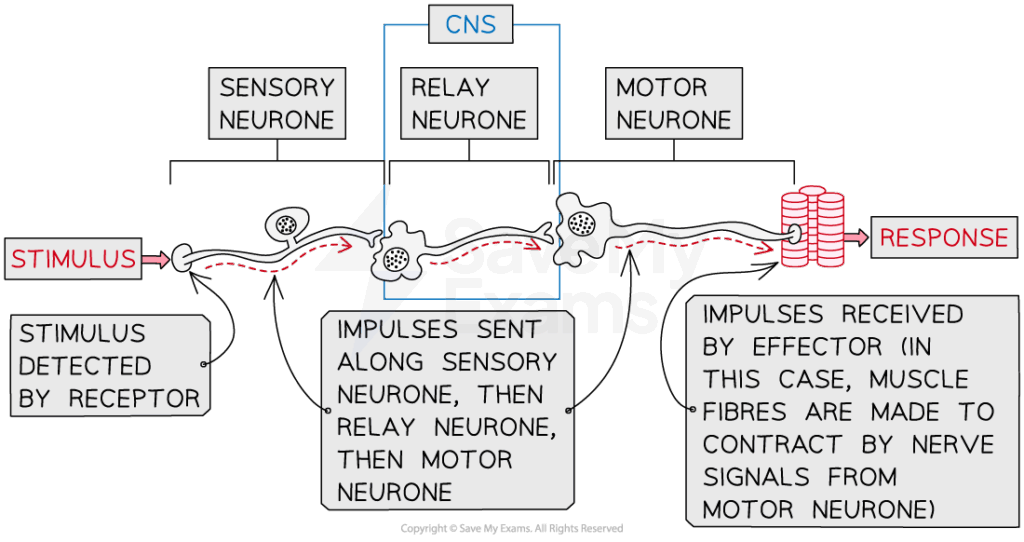

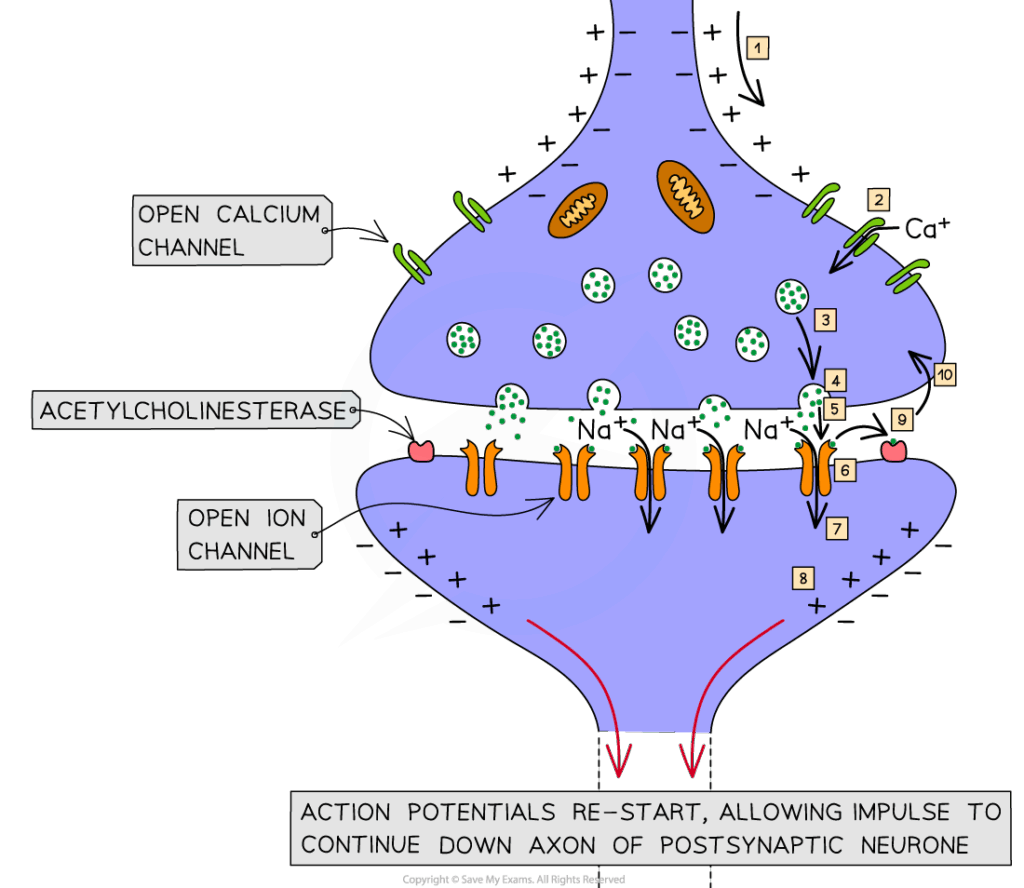

- Receptors detect changes in internal or external environments (e.g., thermoreceptors in skin, chemoreceptors for blood pH).

- Control centres (often in the brain or endocrine glands) process sensory input and compare it to set points.

- Effectors carry out corrective responses (e.g., muscles shivering, glands secreting insulin).

- Constant monitoring and adjustment create dynamic equilibrium, not fixed constancy.

- Examples: thermoregulation, osmoregulation, glucose regulation all follow this pattern.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always describe receptor → control centre → effector when explaining homeostasis. Missing one step often loses marks.

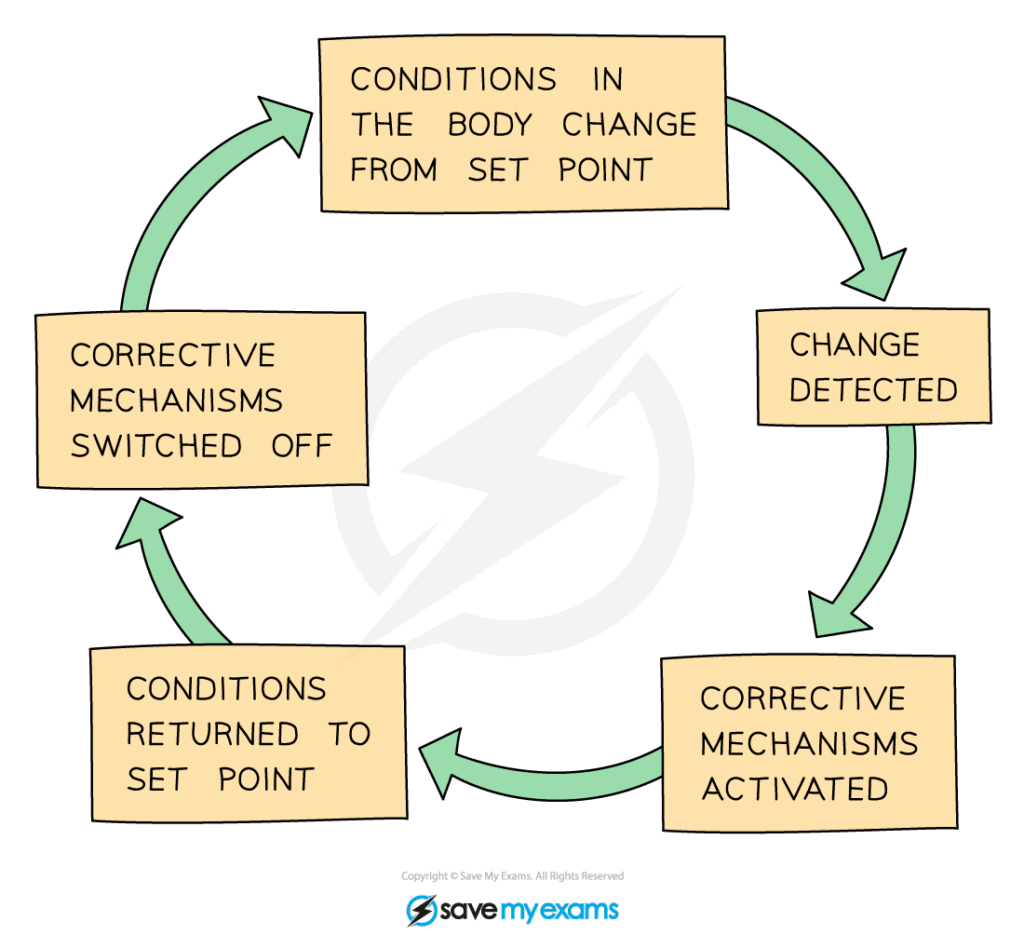

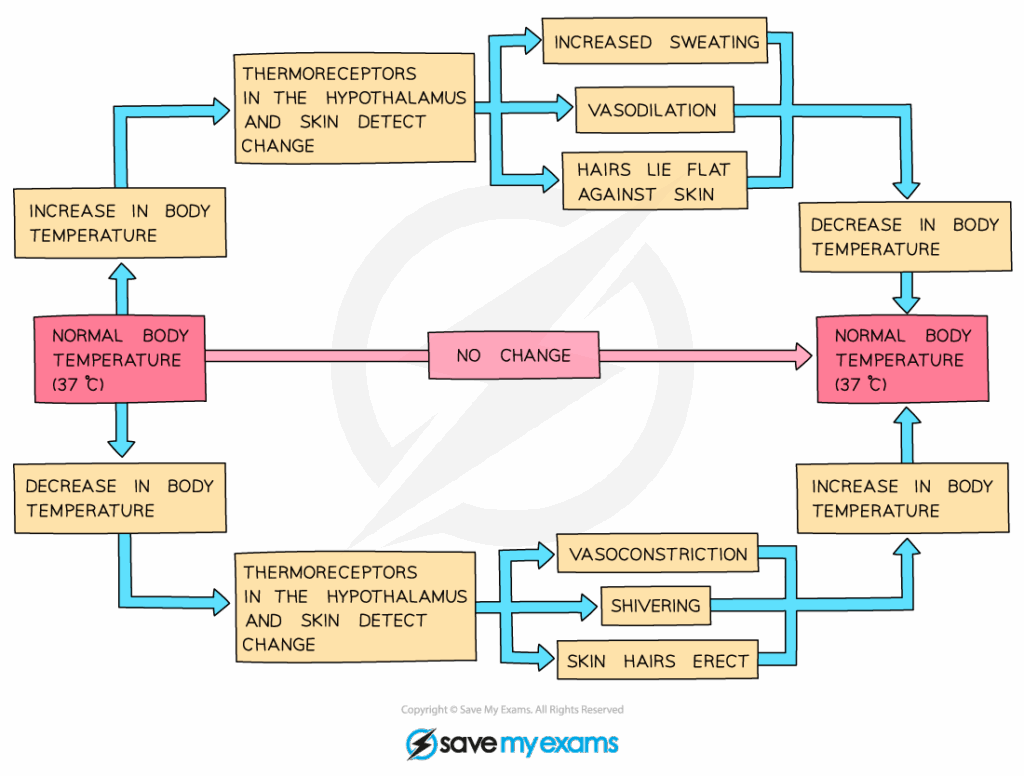

📌 Negative Feedback Mechanisms

- Most homeostatic processes use negative feedback to restore equilibrium.

- Example: Body temperature regulation

- Too hot → vasodilation, sweating → cooling.

- Too cold → vasoconstriction, shivering → warming.

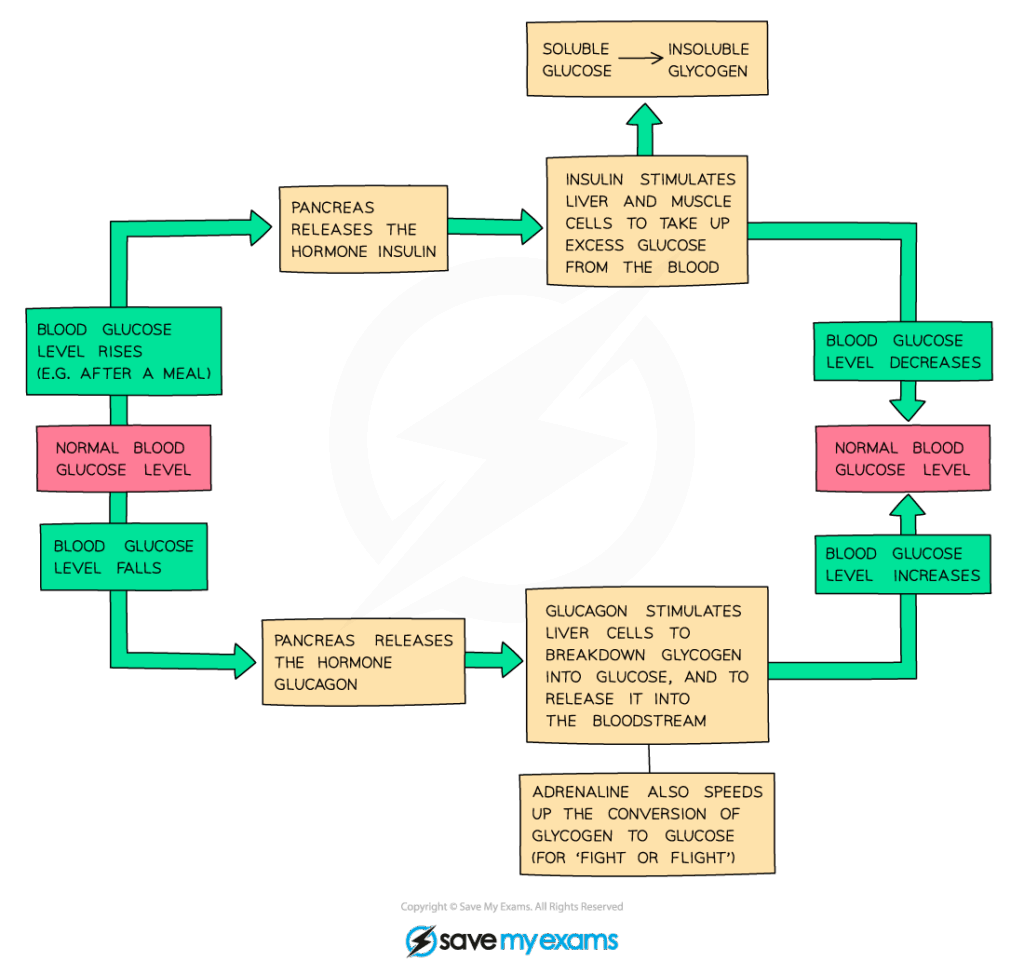

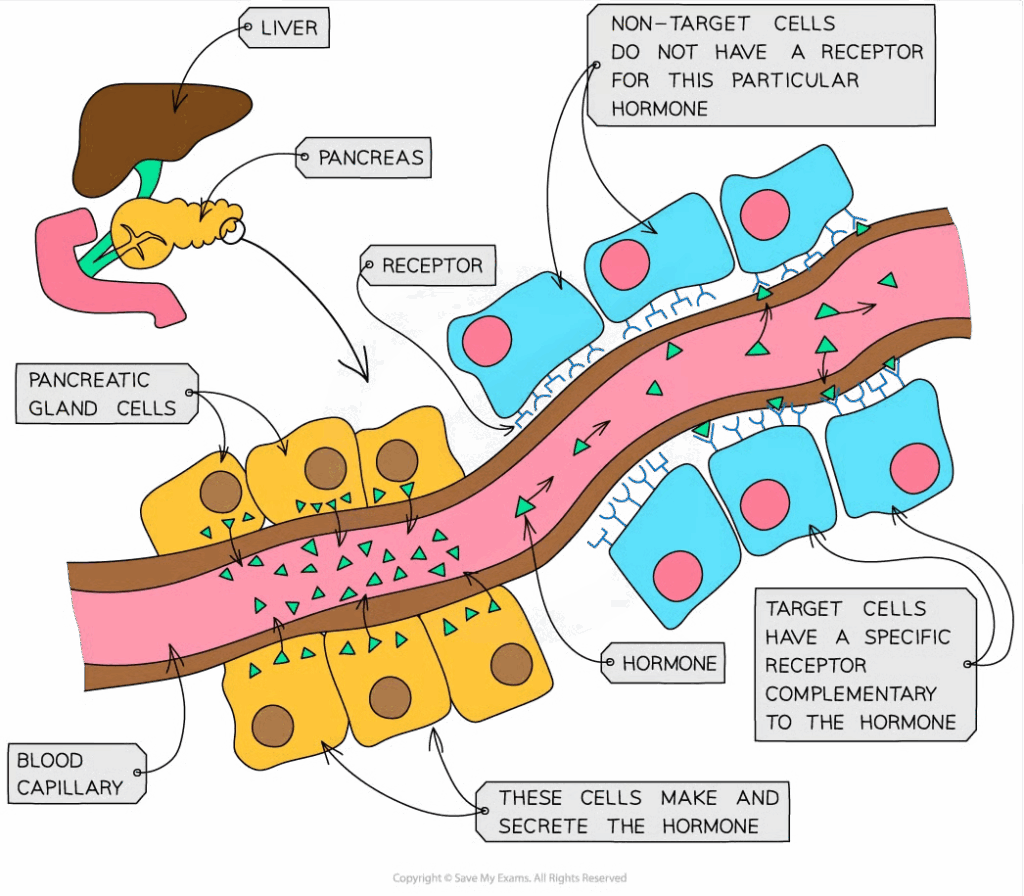

- Example: Blood glucose regulation

- High glucose → insulin secretion → uptake by cells, storage as glycogen.

- Low glucose → glucagon secretion → glycogen breakdown to glucose.

- Negative feedback prevents extreme fluctuations and maintains stability.

- Malfunctions in negative feedback cause disorders like diabetes or thyroid imbalances.

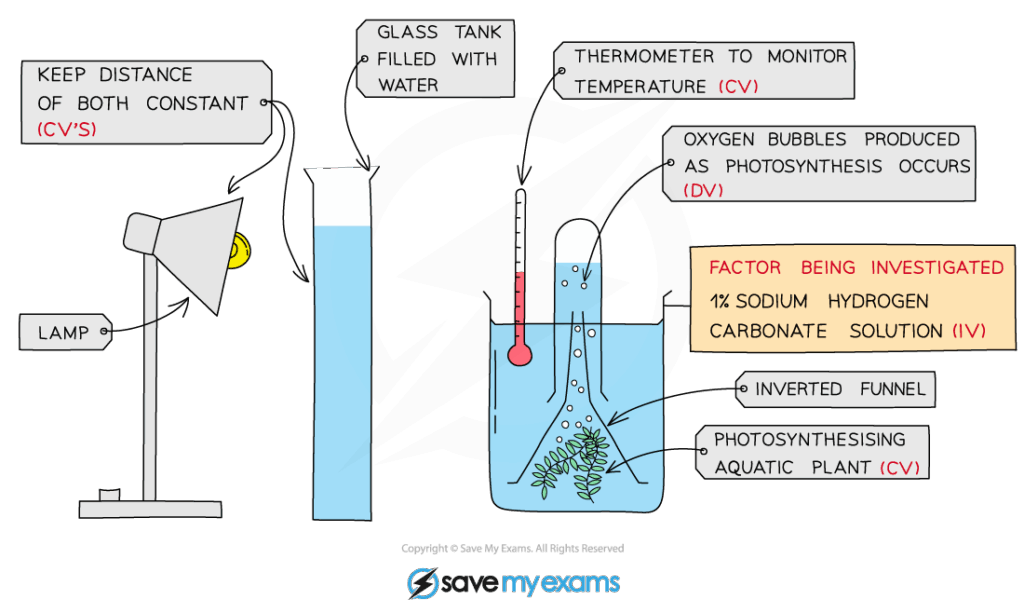

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students can design experiments monitoring body temperature or glucose before and after exercise/food intake, modelling feedback in action (ethical considerations applied).

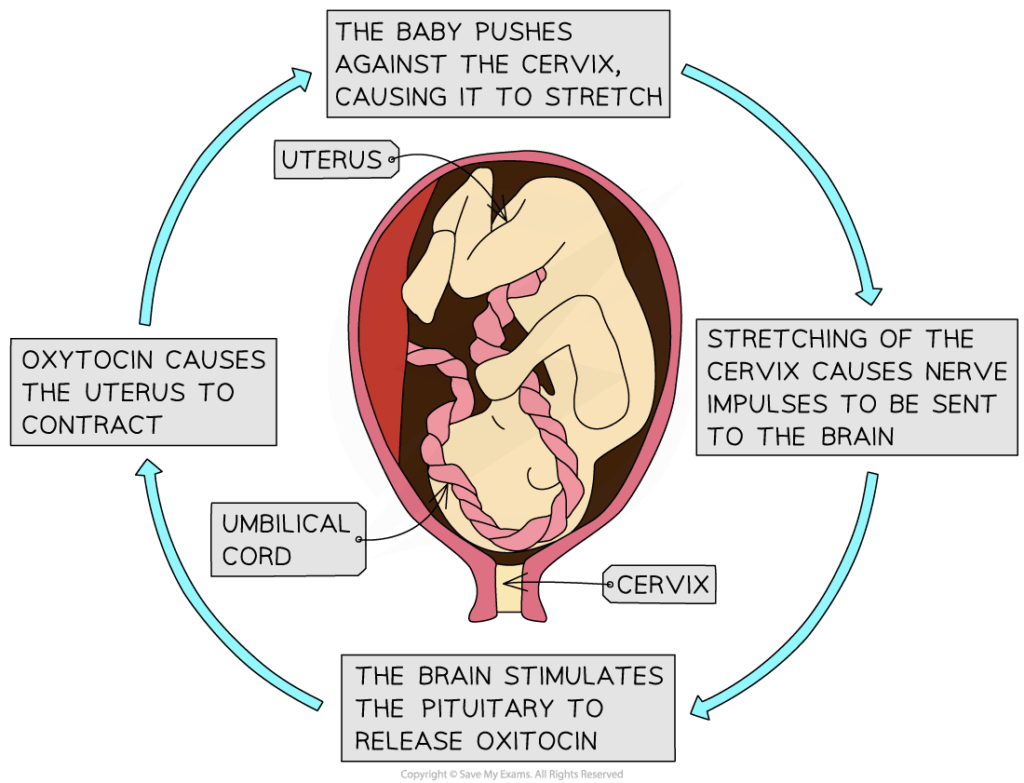

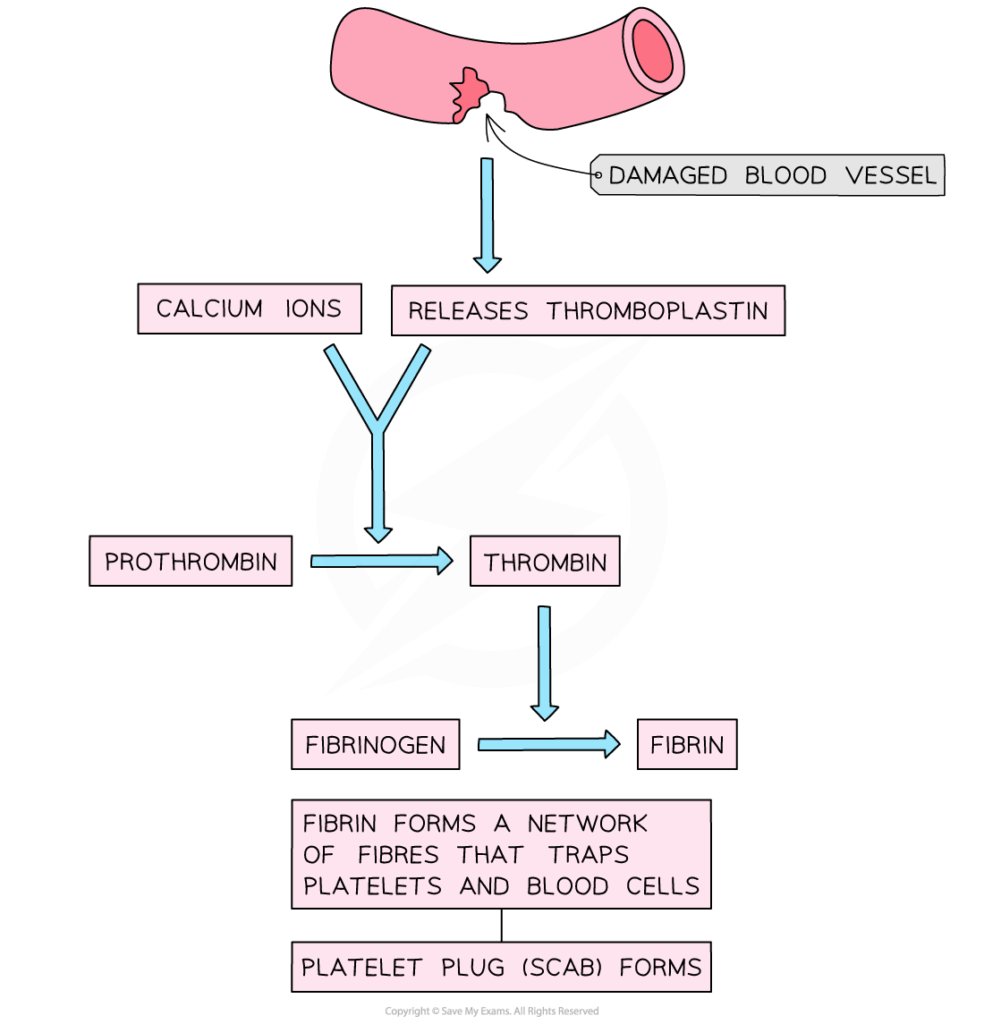

📌 Positive Feedback Mechanisms

- Less common but important in certain biological processes.

- Childbirth: oxytocin stimulates contractions → more oxytocin released → stronger contractions until birth.

- Lactation: suckling triggers prolactin and oxytocin → more milk produced and released.

- Blood clotting: platelets release factors that attract more platelets, forming a clot.

- Unlike negative feedback, positive feedback drives systems away from balance but ensures rapid completion of vital processes.

- Must be tightly regulated, as unchecked positive feedback is harmful.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could explore whether positive feedback loops represent exceptions or integral parts of homeostasis, using examples like parturition or ecological systems.

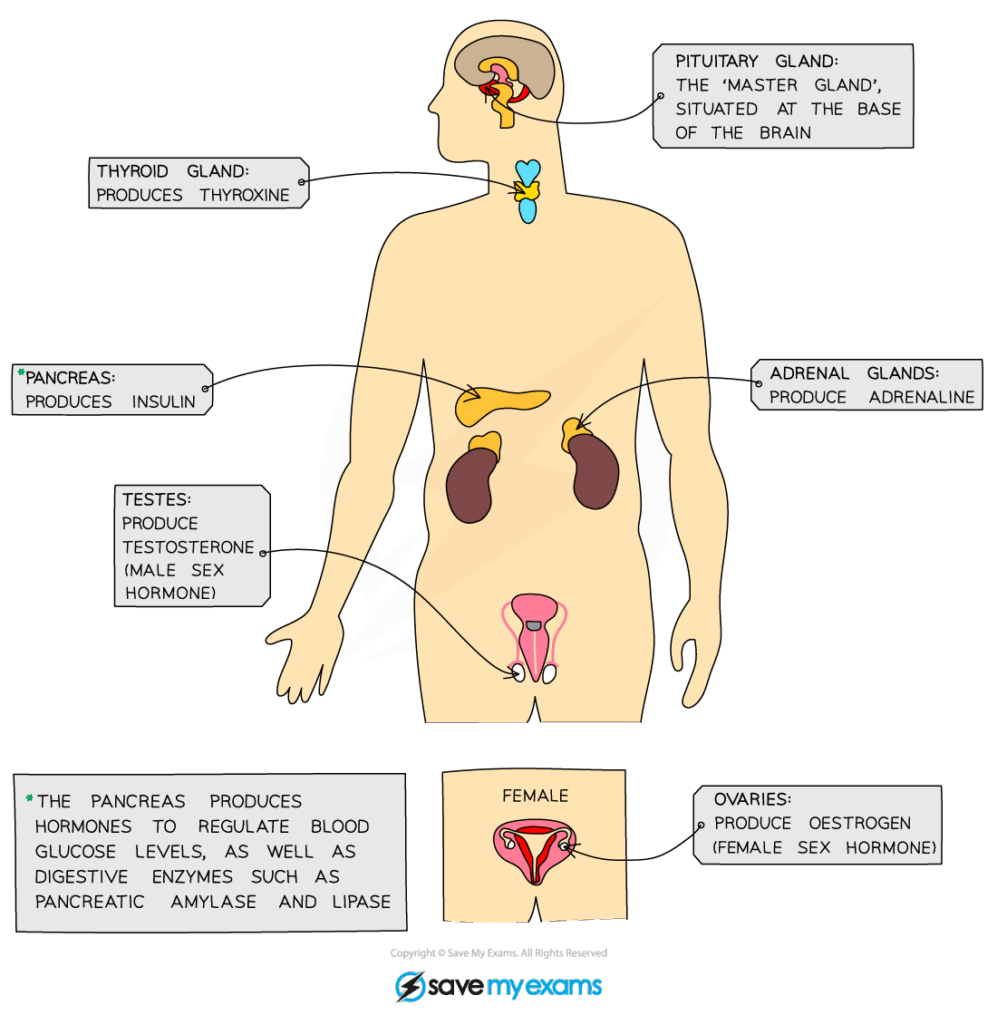

📌 Examples of Homeostatic Regulation

- Thermoregulation: balancing heat production and loss.

- Osmoregulation: kidneys regulate water and ion balance using ADH.

- pH regulation: buffers in blood maintain pH ~7.4; lungs and kidneys remove CO₂ and H⁺.

- Glucose regulation: pancreas hormones balance blood sugar for cellular respiration.

- Gas regulation: respiratory control centres adjust breathing rate to CO₂ and O₂ levels.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could run workshops on healthy lifestyles, showing how hydration, diet, and exercise help maintain homeostasis in the human body.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Failures of homeostasis cause common health problems — diabetes (glucose imbalance), dehydration (osmoregulation failure), hyperthermia and hypothermia (thermoregulation failure). Medical interventions often mimic or restore these mechanisms.

📌 Integration of Multiple Systems

- Homeostasis requires coordination across multiple organ systems.

- Example: Exercise → increased CO₂ → respiratory system increases ventilation; cardiovascular system raises heart rate; nervous and endocrine systems coordinate.

- The hypothalamus is a central hub, integrating neural signals with hormonal control.

- Disruptions in one system can cascade across others (e.g., kidney failure affecting blood pressure and pH).

- Homeostasis is not a single system’s job but the combined effort of nervous, endocrine, respiratory, circulatory, and excretory systems.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Homeostasis is often described as balance around a set point. TOK question: Is this an oversimplified metaphor? In reality, homeostasis is dynamic and constantly fluctuating — so are our scientific models too static to capture this complexity?