C4.2.3 HUMAN IMPACTS ON ENERGY AND MATTER TRANSFERS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Eutrophication | Excessive nutrient enrichment in water leading to algal blooms and oxygen depletion. |

| Greenhouse gases | Atmospheric gases (CO₂, CH₄, N₂O) that trap heat, driving climate change. |

| Ecological footprint | The measure of human demand on Earth’s ecosystems relative to their capacity. |

| Bioaccumulation | The build-up of toxic substances within organisms over time. |

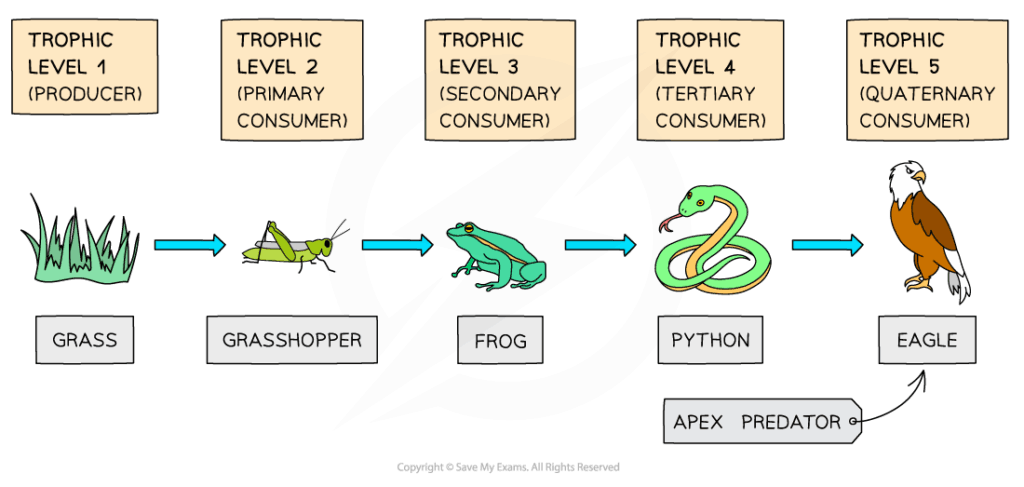

| Biomagnification | Increase in toxin concentration at higher trophic levels in food chains. |

| Sustainability | The ability to use resources in ways that meet current needs without compromising future generations. |

📌Introduction

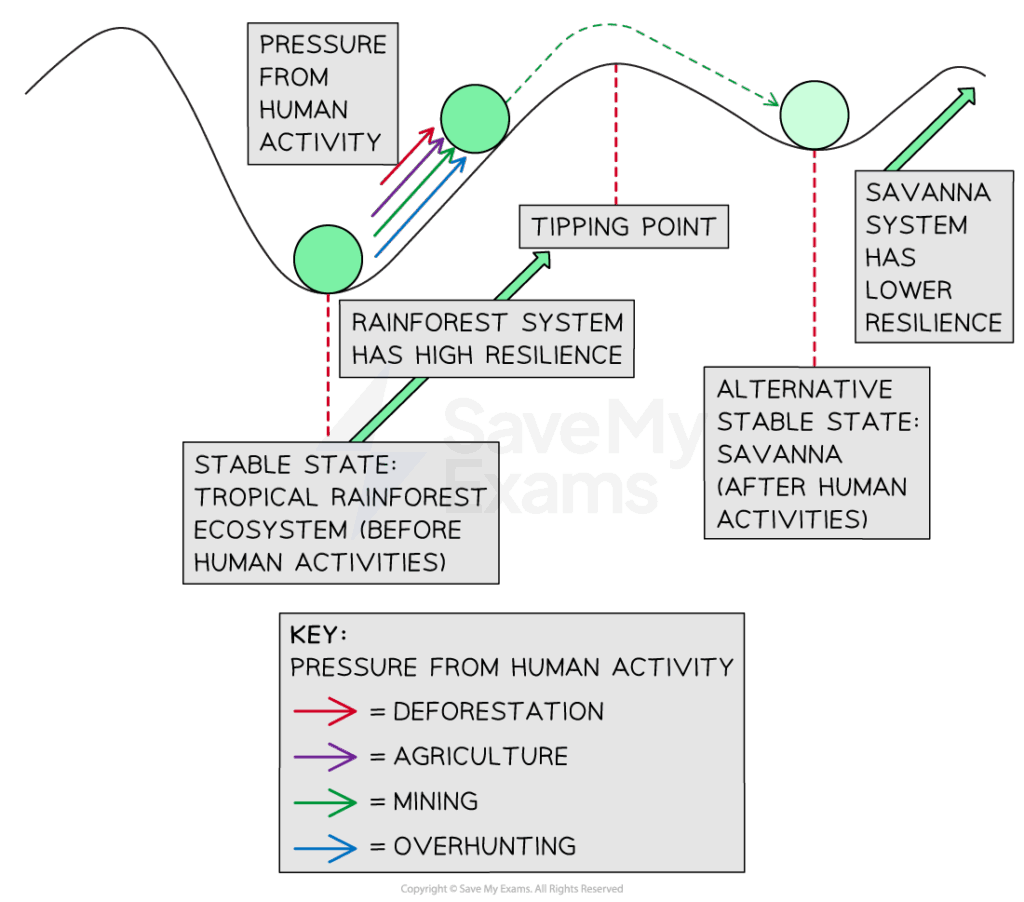

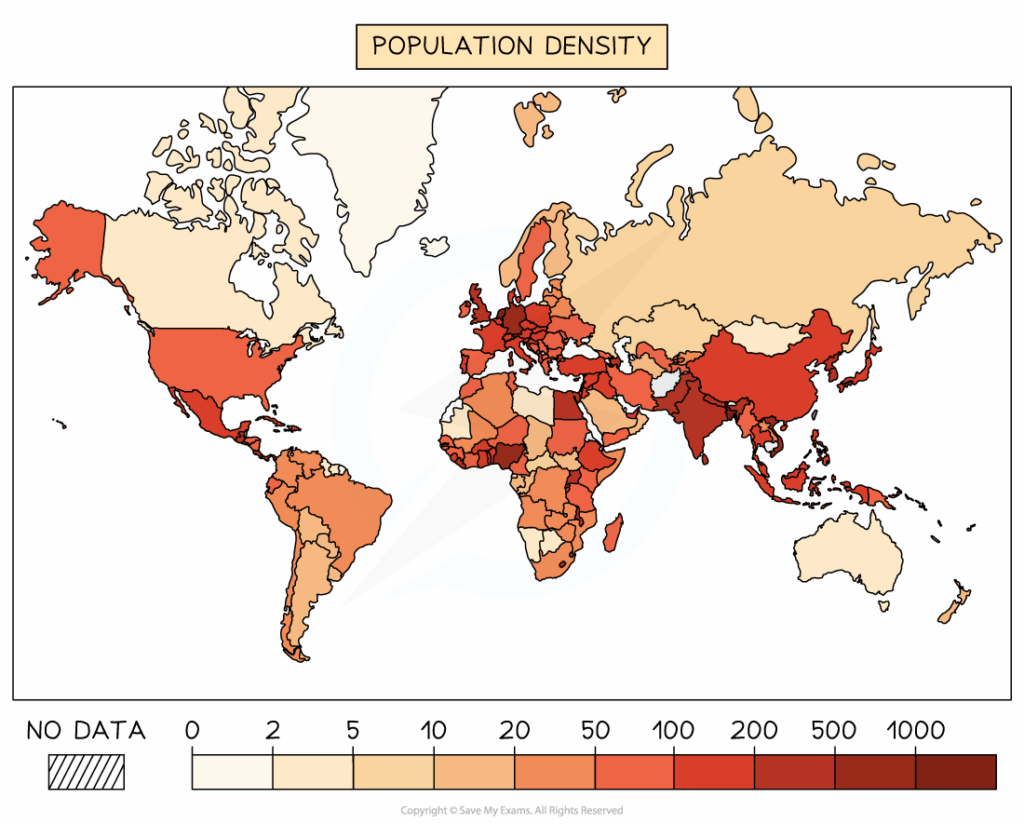

Human activity has profoundly altered natural transfers of energy and matter. Agriculture, industry, and urbanisation disrupt nutrient cycles, reduce productivity, and degrade ecosystem stability. Climate change, pollution, and habitat destruction further magnify these impacts. Understanding these disruptions is critical for developing strategies toward sustainability and global environmental management.

📌 Agricultural Impacts

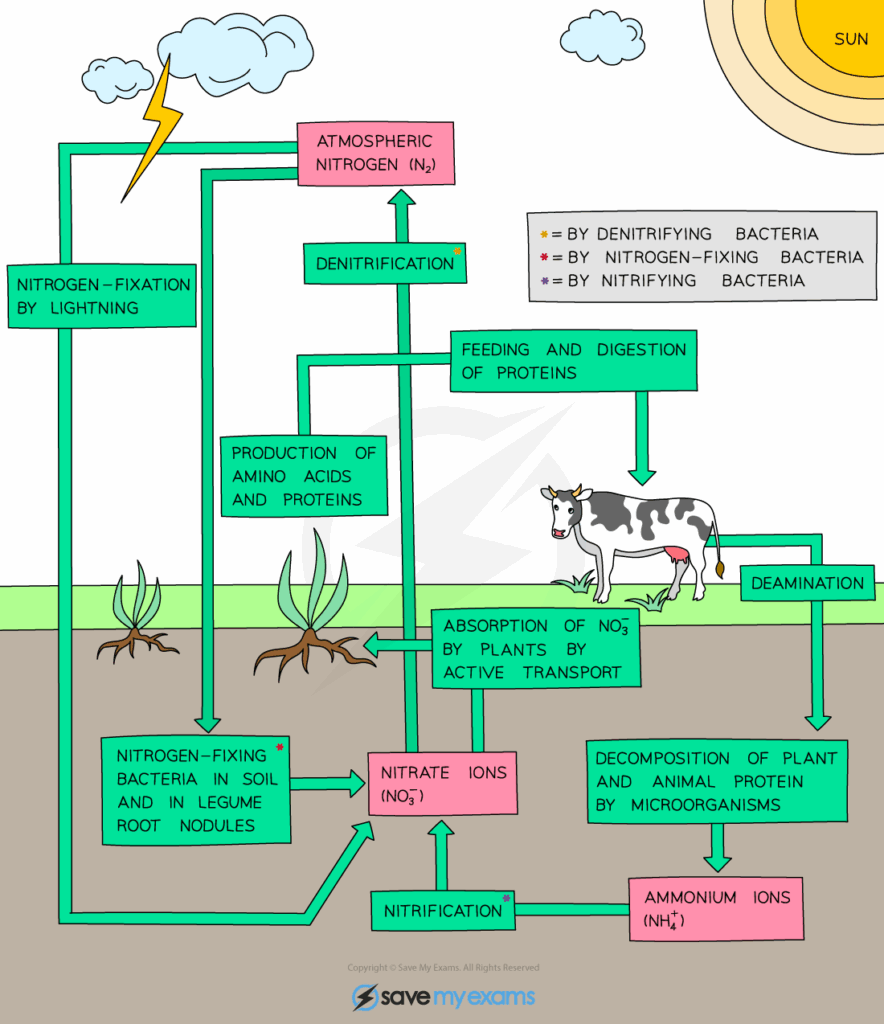

- Fertilisers boost productivity but disrupt nitrogen and phosphorus cycles.

- Pesticides reduce pest populations but bioaccumulate in ecosystems.

- Monoculture farming lowers biodiversity and resilience.

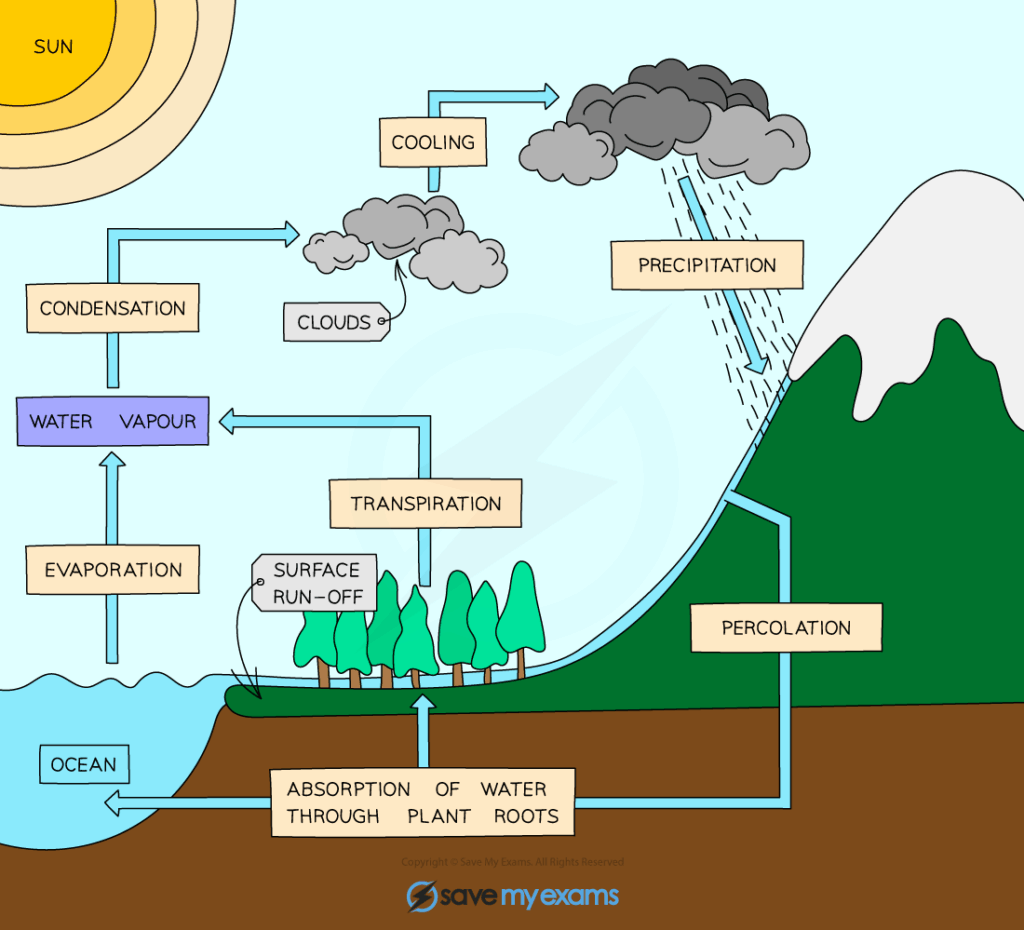

- Irrigation alters water cycles, depleting aquifers.

- Intensive livestock farming increases methane emissions.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always distinguish between short-term benefits (increased yields) and long-term costs (eutrophication, soil degradation).

📌 Industrial and Urban Impacts

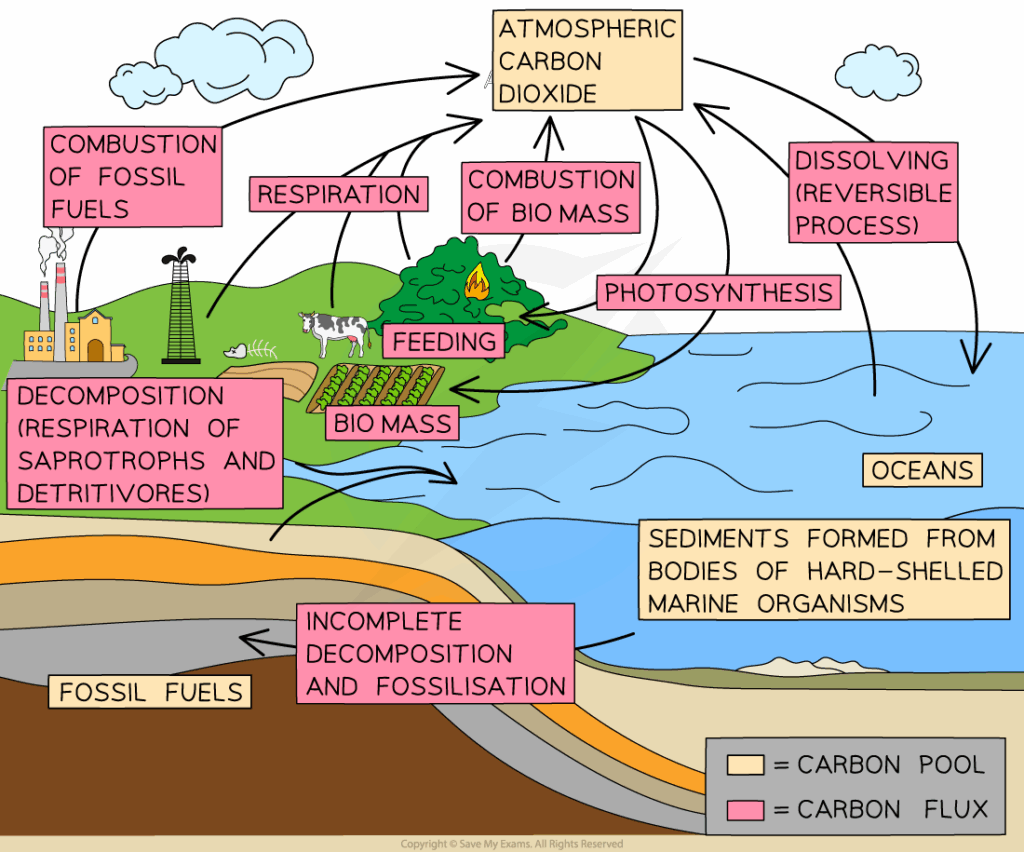

- Burning fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases, altering the carbon cycle.

- Industrial waste pollutes air, soil, and water.

- Urbanisation increases runoff, reducing infiltration and groundwater recharge.

- Heat islands alter local climate and energy flow.

- Deforestation for industry reduces carbon sinks and disrupts water cycling.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could test local water bodies for nitrate/phosphate levels to evaluate eutrophication from agriculture or urban runoff.

📌 Climate Change and Greenhouse Gases

- Increased CO₂, methane, and nitrous oxide enhance greenhouse effect.

- Leads to global warming, altered precipitation, rising sea levels.

- Ocean acidification harms coral reefs and marine food webs.

- Melting permafrost releases methane, creating feedback loops.

- Ecosystems shift ranges, threatening biodiversity.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could analyse carbon footprints of different lifestyles, linking human behaviour to measurable ecosystem impacts.

📌 Pollution and Toxins

- Heavy metals (mercury, lead) bioaccumulate in organisms, harming health.

- Biomagnification increases toxin levels at higher trophic levels (e.g., DDT in birds of prey).

- Plastic pollution disrupts marine ecosystems and energy flow.

- Oil spills destroy habitats and reduce productivity.

- Pollution disrupts both nutrient cycles and energy transfer.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could organise clean-up drives or awareness campaigns on reducing plastic use and sustainable consumption.

🌍 Real-World Connection: The Minamata disease (Japan) showed mercury biomagnification effects. DDT restrictions arose from ecological damage (e.g., Silent Spring). Climate change remains the biggest global consequence of human impacts.

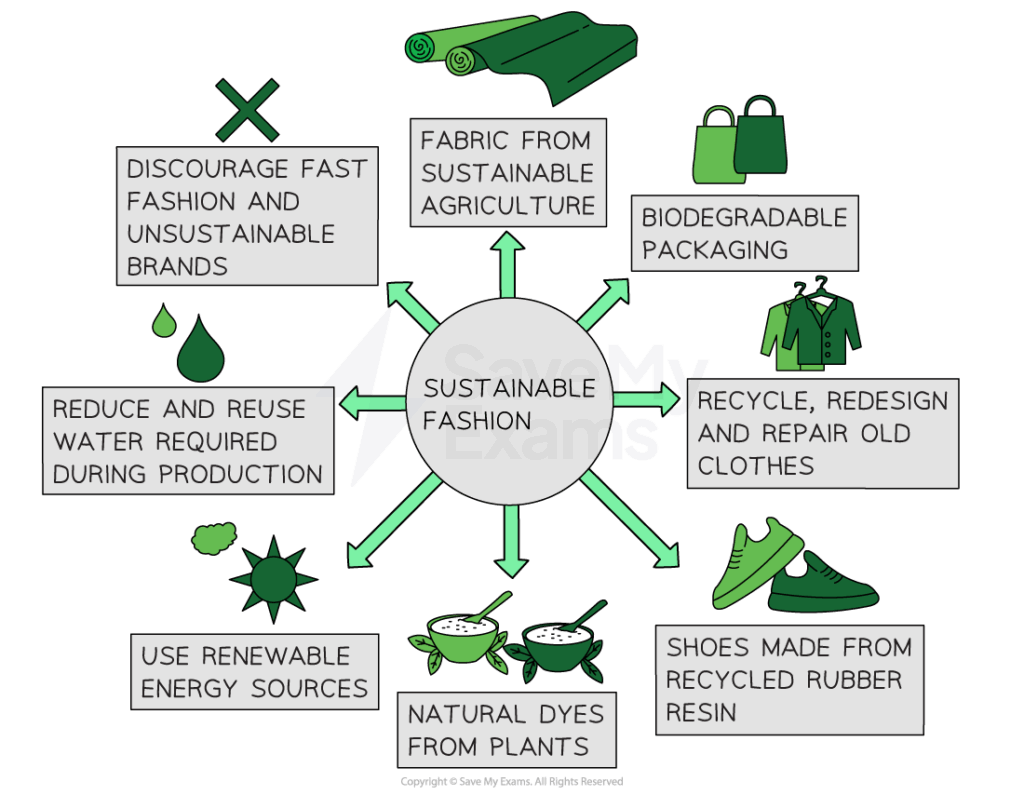

📌 Sustainability and Solutions

- Sustainable agriculture: crop rotation, reduced fertiliser use, organic methods.

- Renewable energy reduces CO₂ emissions.

- Conservation: protecting carbon sinks (forests, wetlands) and biodiversity.

- Recycling and waste management reduce ecological footprint.

- Education and policy drive sustainable behaviour globally.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Human impacts are studied with scientific data, but solutions involve ethics, politics, and culture. TOK question: How do value systems influence what counts as “sustainable”?