D2.1.1 CELL CYCLE AND CHECKPOINTS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cell cycle | The series of stages a cell goes through from one division to the next. |

| Interphase | The phase between divisions, consisting of G1, S, and G2. |

| Checkpoints | Control mechanisms that ensure accuracy of cell cycle progression. |

| Cyclins | Regulatory proteins controlling progression through the cell cycle. |

| CDKs (cyclin-dependent kinases) | Enzymes activated by cyclins to phosphorylate target proteins. |

| Apoptosis | Programmed cell death triggered if errors cannot be corrected. |

📌Introduction

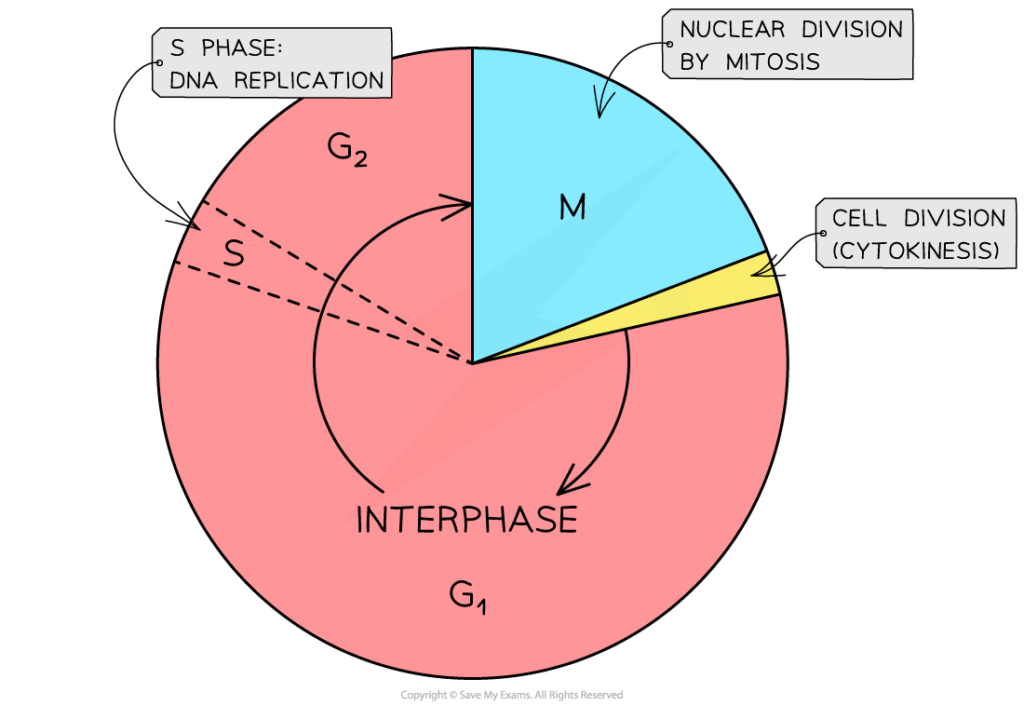

The cell cycle is a tightly regulated process ensuring cells grow, replicate DNA, and divide accurately. Interphase makes up the majority of the cycle, preparing cells for mitosis or meiosis. Checkpoints safeguard against errors, preventing uncontrolled division and cancer. Cyclins and CDKs are key molecular regulators, ensuring the cycle proceeds only when conditions are favourable.

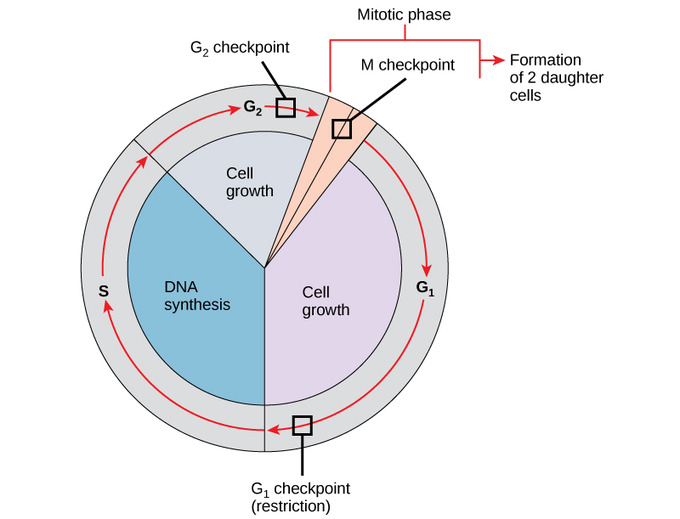

📌 Phases of the Cell Cycle

- G1 phase: cell grows, produces RNA, proteins, and organelles.

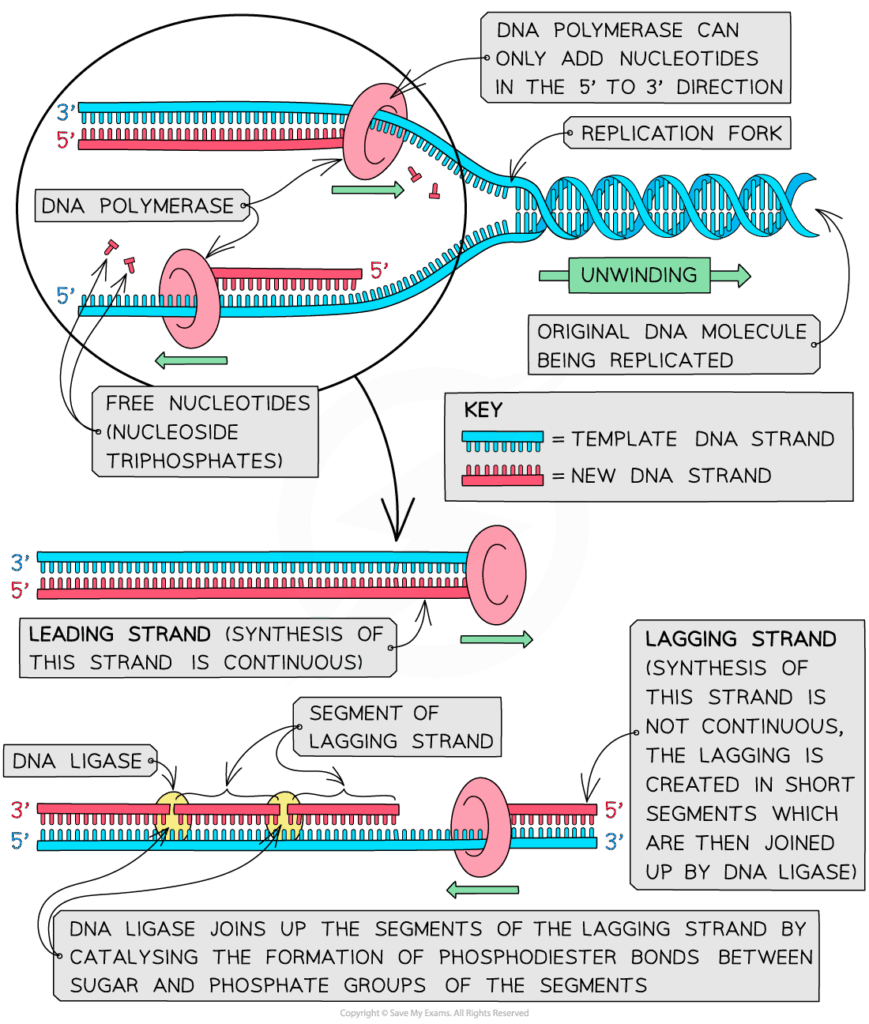

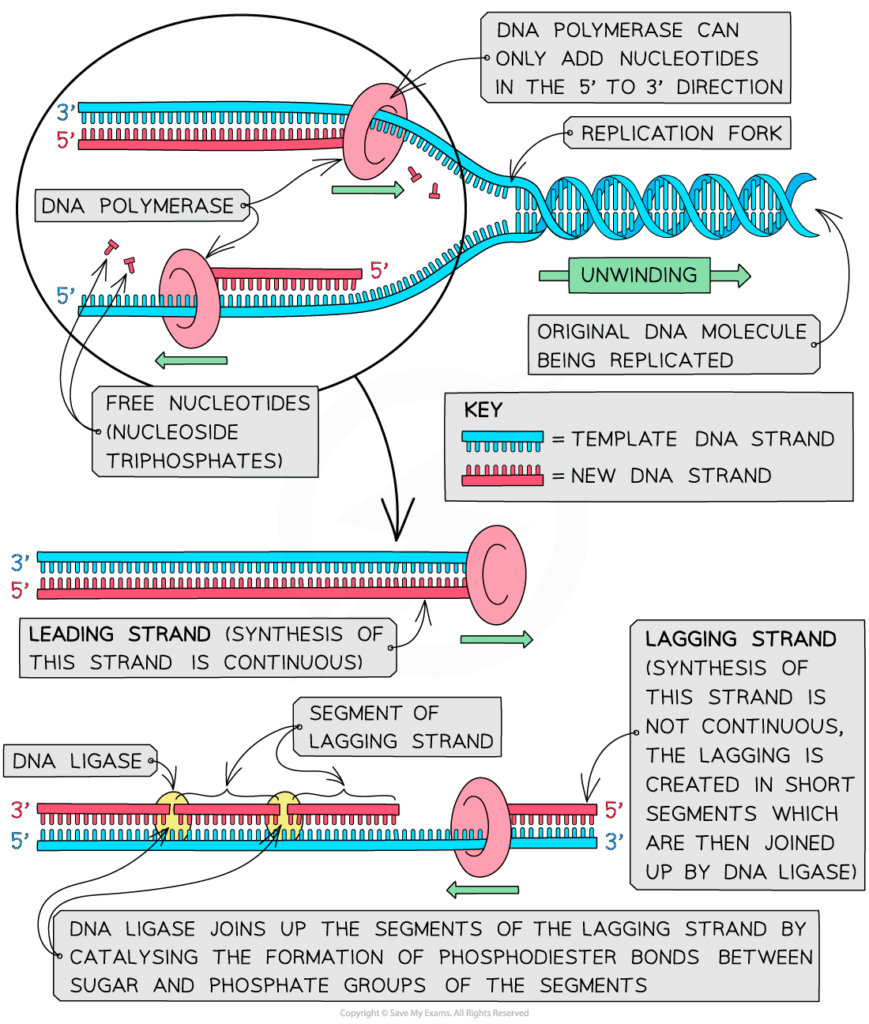

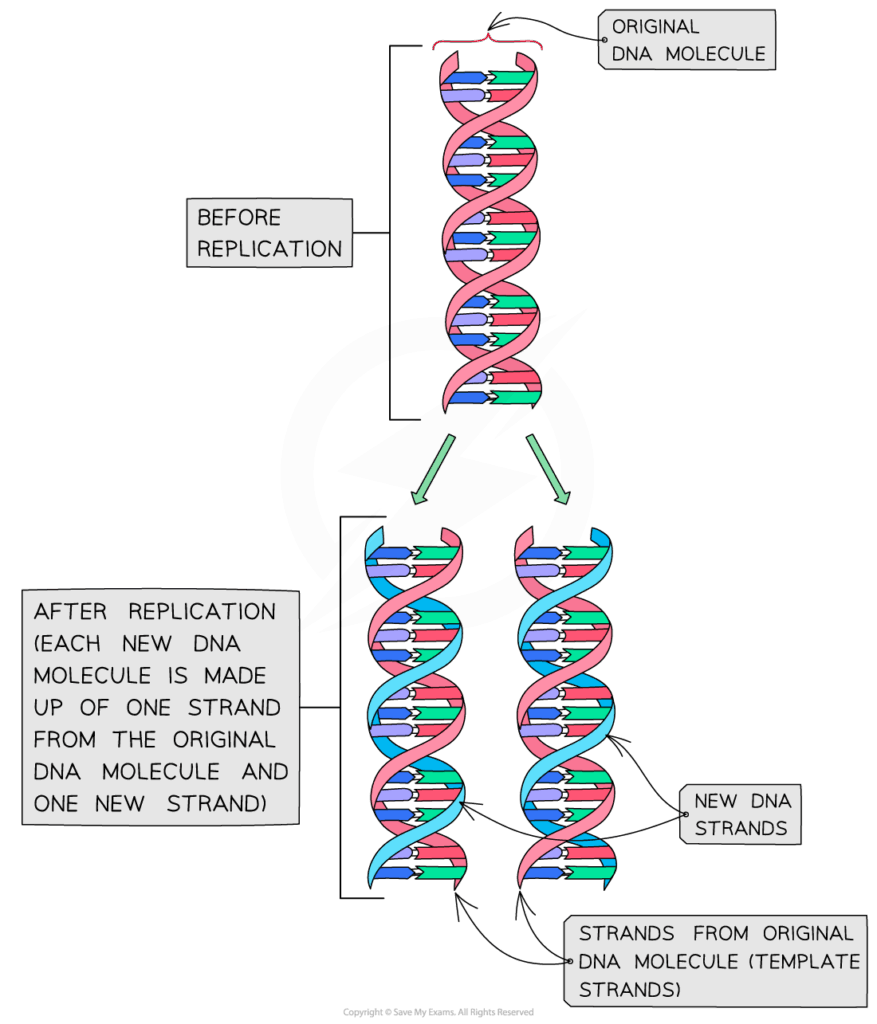

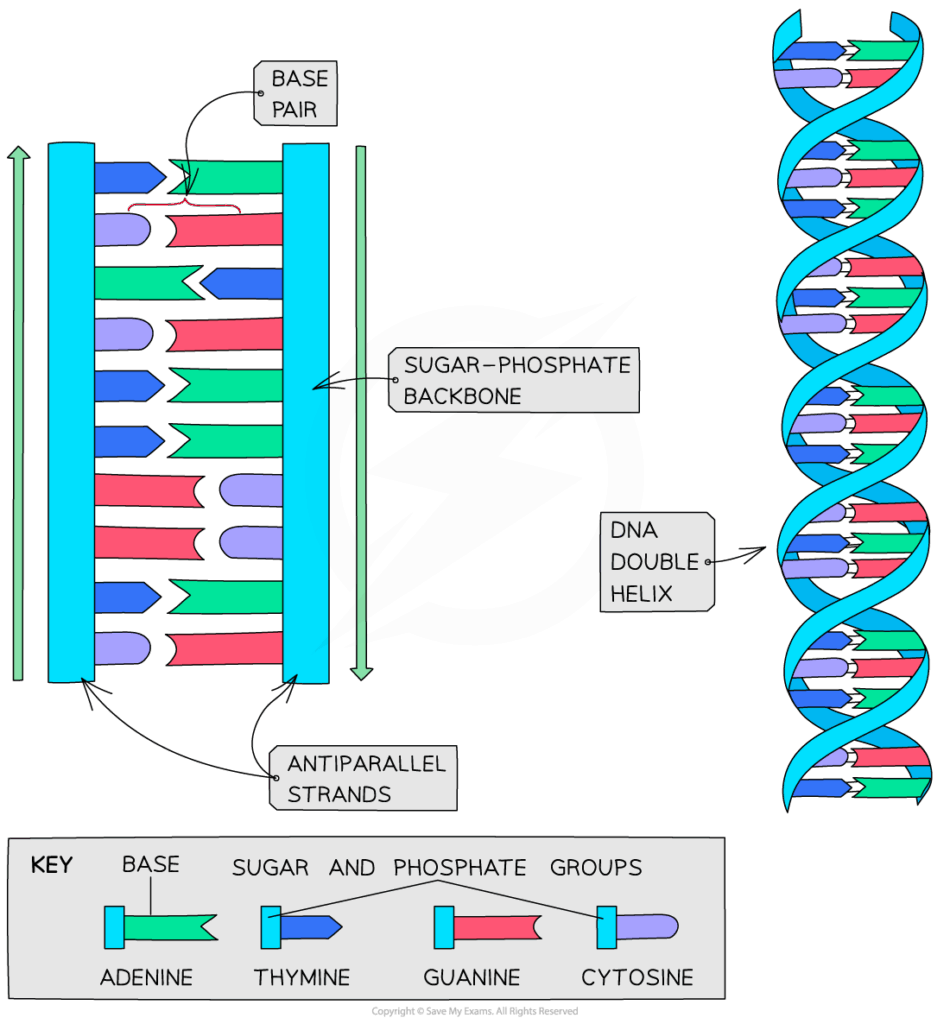

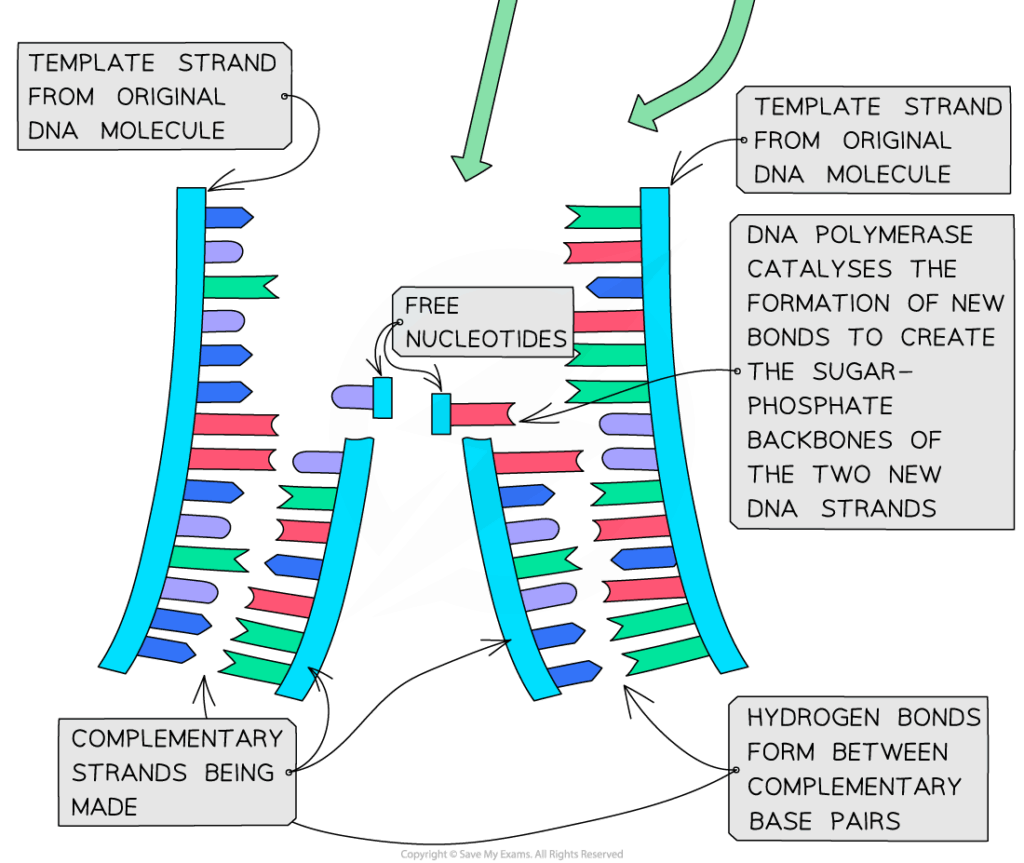

- S phase: DNA replication occurs; each chromosome duplicates.

- G2 phase: preparation for division; checks DNA integrity.

- M phase: nuclear division (mitosis/meiosis) and cytokinesis.

- Interphase dominates (~90% of cell cycle).

🧠 Examiner Tip: Don’t confuse interphase as a “resting” stage — it is metabolically active and essential for preparation.

📌 Checkpoints in Cell Cycle

- G1 checkpoint: assesses size, nutrients, DNA damage.

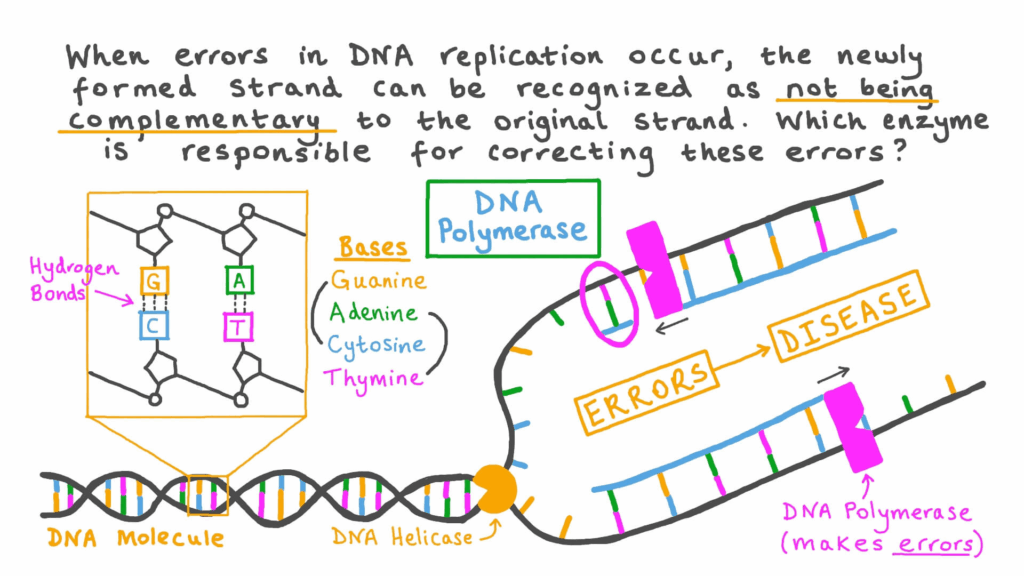

- G2 checkpoint: ensures DNA is fully replicated and undamaged.

- Metaphase (spindle) checkpoint: checks chromosome attachment to spindle fibres.

- If conditions fail, cycle halts for repair or apoptosis.

- Prevents propagation of mutations.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students can study onion root tips to calculate mitotic index as a measure of cell cycle activity.

📌 Cyclins and CDKs

- Cyclins rise and fall during cycle phases.

- Cyclins bind CDKs, forming active complexes.

- Complexes phosphorylate proteins, driving phase transitions.

- Example: cyclin D → G1 progression; cyclin B → mitosis entry.

- Dysregulation of cyclins → uncontrolled cell division (cancer).

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how environmental stressors affect checkpoint regulation, e.g., UV light and DNA repair.

📌 Consequences of Checkpoint Failure

- Uncontrolled cell division → tumours and cancer.

- Damaged DNA passed to daughter cells.

- Checkpoint mutations linked to p53 failure.

- Therapeutic target: drugs modulating cyclins/CDKs in cancer treatment.

- Balance between repair and apoptosis critical for survival.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could run awareness projects on cancer prevention, linking lifestyle choices to cell cycle regulation.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Chemotherapy drugs target cell cycle processes (e.g., mitotic spindle inhibitors).

📌 Integration with Other Systems

- Cell cycle regulation tied to organism growth and repair.

- Endocrine signals (hormones) can influence proliferation.

- Immune cells rely on rapid cycling during infections.

- Stem cells demonstrate controlled cycling vs differentiation.

- Coordination prevents overgrowth and maintains tissue health.

🔍 TOK Perspective: The cell cycle is modelled as a linear series of phases. TOK issue: To what extent do such models capture the complexity of overlapping signals and feedback?