B2.2 ORGANELLES AND COMPARTMENTALIZATION

Author: Admin

-

-

B2.1 MEMBRANES AND MEMBRANE TRANSPORT

-

B1.2 PROTEINS

-

B1.1 CARBOHYDRATES AND LIPIDS

-

D4.3.3 MITIGATION AND ADAPTATION STRATEGIES

📌Definition Table

Term Definition Mitigation Actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or enhance carbon sinks to slow climate change. Adaptation Adjustments in ecological, social, or economic systems to minimise harm from climate change impacts. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) Technology to remove CO₂ from emissions and store it underground. Renewable energy Energy from sources like solar, wind, and hydro that do not emit GHGs. Climate resilience Ability of systems to absorb disturbances and maintain function under changing conditions. Paris Agreement International treaty aiming to limit warming to below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels. 📌Introduction

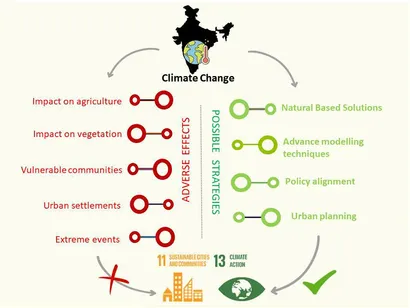

Addressing climate change requires both mitigation to tackle root causes and adaptation to cope with unavoidable impacts. Mitigation focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions through energy transition, efficiency, and carbon sequestration. Adaptation strategies help societies and ecosystems adjust, from climate-resilient crops to coastal defences. Effective action requires cooperation across scales, integrating science, policy, economics, and community engagement.

📌 Mitigation Approaches

- Transition to renewable energy (solar, wind, hydro, geothermal).

- Improving energy efficiency in transport, industry, and housing.

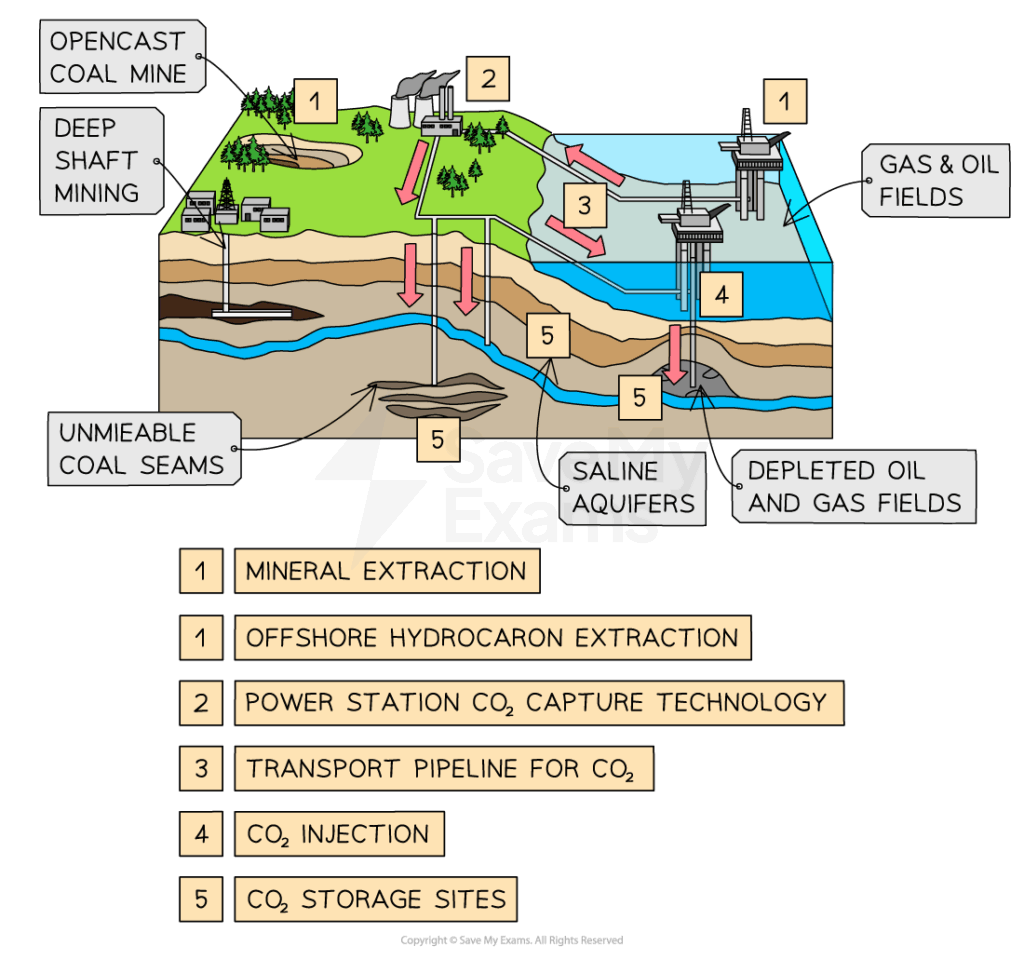

- Carbon capture and storage (CCS) for industrial emissions.

- Reforestation and afforestation to increase carbon sinks.

- Policy tools: carbon pricing, emissions trading, and subsidies for green tech.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Distinguish clearly between mitigation (reducing the cause) and adaptation (managing the effects).

📌 Adaptation Strategies

- Developing drought-resistant and flood-tolerant crops.

- Building sea walls and managed retreat in coastal zones.

- Enhancing water storage and irrigation efficiency.

- Designing climate-resilient infrastructure (e.g., flood-proof housing).

- Protecting and restoring ecosystems to provide natural buffers.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Projects could model effects of tree planting on CO₂ absorption, or compare water-use efficiency in different crop varieties under stress conditions.

📌 International and Local Action

- Paris Agreement (2015): global cooperation to limit warming to <2 °C.

- Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) set by each country.

- Local initiatives: community renewable projects, urban greening.

- NGOs and grassroots movements advocate climate justice.

- Integration of science, policy, and education critical for success.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could evaluate effectiveness of mitigation vs adaptation in a particular country, combining data analysis with policy evaluation.

📌 Challenges and Trade-Offs

- Economic costs of transition vs long-term benefits.

- Resistance from industries reliant on fossil fuels.

- Unequal vulnerability: poorer nations face disproportionate impacts.

- Geoengineering proposals raise ethical and ecological concerns.

- Balancing immediate needs with long-term sustainability.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could initiate school sustainability projects — reducing waste, promoting renewable energy use, or climate awareness campaigns.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Climate change is already shaping geopolitics (climate refugees, food insecurity). Effective mitigation and adaptation are essential for human security.

📌 Resilience and Future Pathways

- Building resilience requires integrating ecological, economic, and social systems.

- Ecosystem-based adaptation (mangrove restoration, wetlands) provides co-benefits.

- Innovation in energy storage and carbon removal may transform future scenarios.

- Equity and justice central to climate strategies.

- Collective action determines whether warming is stabilised or escalates.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Mitigation involves ethical and political decisions. TOK issue: To what extent is science sufficient to solve climate change, and where do values and cultural perspectives play a decisive role?

📝 Paper 2: Questions may require evaluating mitigation vs adaptation, explaining specific strategies, or interpreting data on emissions and climate projections.

-

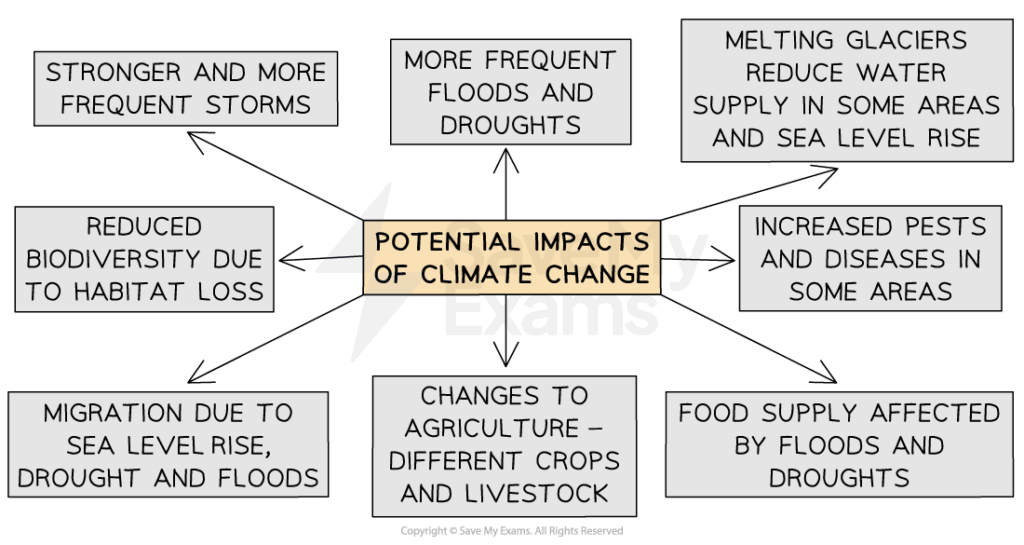

D4.3.2 BIOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL IMPACTS

📌Definition Table

Term Definition Phenology Timing of biological events such as flowering, migration, and breeding. Range shifts Movement of species distributions in response to changing climates. Coral bleaching Loss of symbiotic algae from corals due to stress, often linked to warming seas. Ecosystem services Benefits provided by ecosystems, such as pollination, water purification, and carbon sequestration. Trophic mismatch Disruption between timing of species interactions (e.g., predator and prey cycles). Biodiversity loss Decline in variety of species and genetic resources due to climate and habitat change. 📌Introduction

Climate change impacts biological systems at every level, from molecular physiology to global ecosystems. Rising temperatures, altered precipitation, and extreme events disrupt life cycles, migration, and reproduction. Ecosystems face shifts in community composition, species extinction risks, and altered services. These effects cascade through food webs, destabilising ecological interactions and human systems that depend on them

📌 Phenological Changes

- Plants flowering earlier in spring, altering pollination networks.

- Migratory birds arriving earlier or mismatched with food peaks.

- Insects emerging at different times, disrupting predator–prey synchrony.

- Amphibians breeding earlier in response to warming.

- Seasonal cues increasingly unreliable under shifting climates.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Use specific examples (e.g., UK butterflies emerging earlier) to illustrate impacts; generic statements lose marks.

📌 Range Shifts and Extinction Risk

- Species moving poleward or upslope to track suitable climates.

- Arctic species (polar bears, walruses) losing habitat due to ice melt.

- Alpine species confined to shrinking high-altitude zones.

- Coral reefs threatened by warming seas and acidification.

- Species unable to migrate or adapt risk extinction.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Local surveys could track species distributions over time (e.g., plants along an elevation gradient), linking observed changes to climate patterns.

📌 Ecosystem Disruptions

- Coral bleaching events causing large-scale reef mortality.

- Forest dieback from droughts, pests, and wildfires.

- Ocean acidification harming shell-building organisms.

- Shifts in fisheries as marine species move poleward.

- Cascading effects destabilise food webs and ecosystem services.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could focus on ecological resilience — e.g., how climate stress alters keystone species, changing entire ecosystem dynamics.

📌 Human Dependence on Ecosystems

- Agriculture disrupted by droughts and shifting growing zones.

- Loss of pollinators threatens food security.

- Freshwater supplies reduced by shrinking glaciers.

- Fisheries collapse affecting livelihoods of millions.

- Ecosystem service degradation increases human vulnerability.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could collaborate with conservation groups to raise awareness about protecting pollinators or planting climate-resilient vegetation.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Indigenous communities and small-island nations are already experiencing existential threats from rising seas and biodiversity loss.

📌 Feedbacks Between Biology and Climate

- Deforestation reduces carbon sinks, accelerating warming.

- Permafrost thaw releases methane, intensifying greenhouse effect.

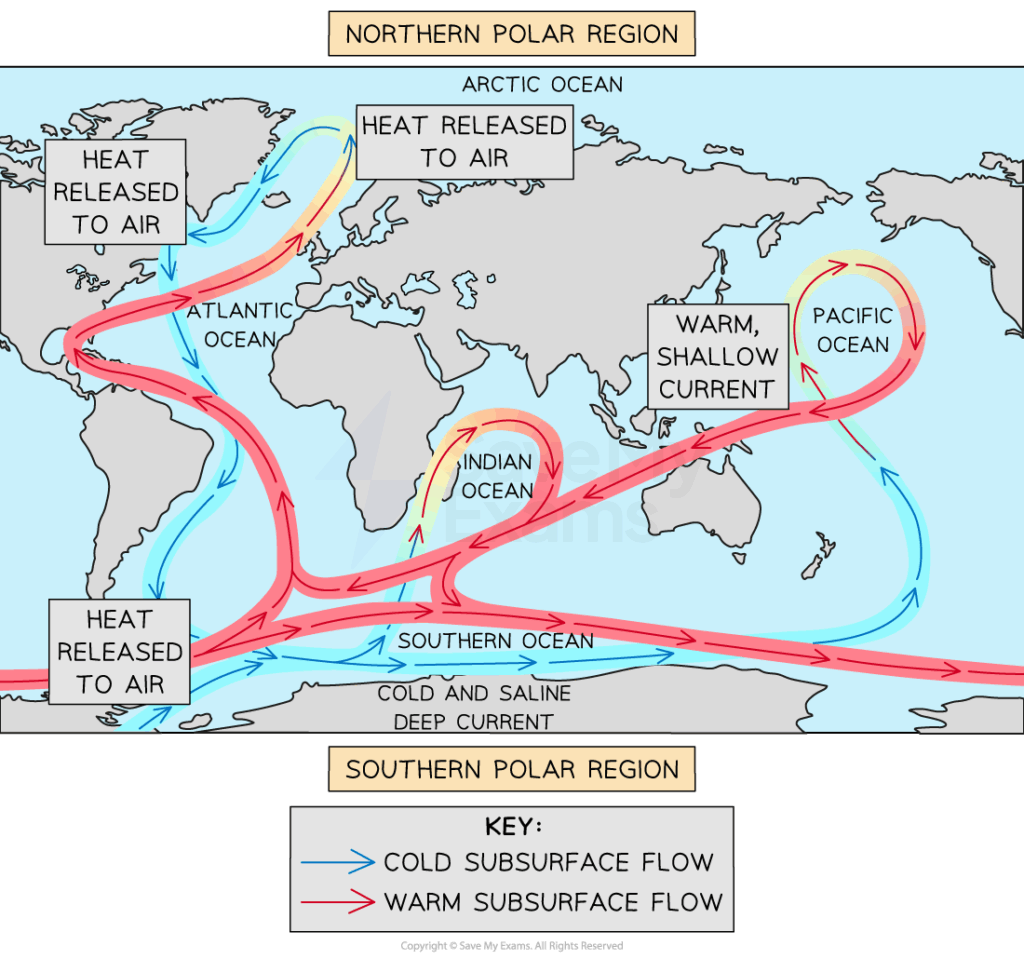

- Forest dieback reduces evapotranspiration, altering rainfall patterns.

- Ocean ecosystem collapse reduces CO₂ absorption.

- Biology both suffers from and amplifies climate change.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Predicting ecological futures involves uncertainty. TOK issue: How do scientists balance probabilistic predictions with public communication to inspire action without overstating certainty?

📝 Paper 2: Likely questions on examples of phenology shifts, species range changes, coral bleaching, or analysis of biodiversity–climate interactions.

-

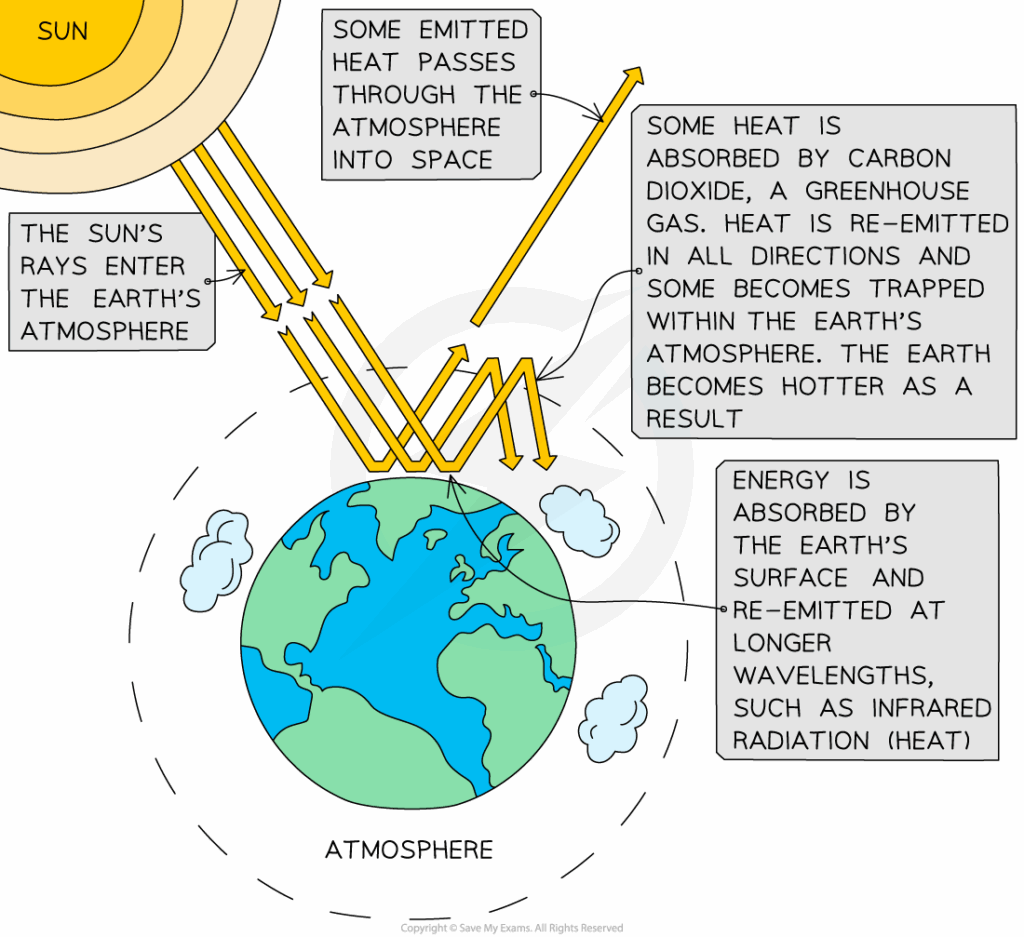

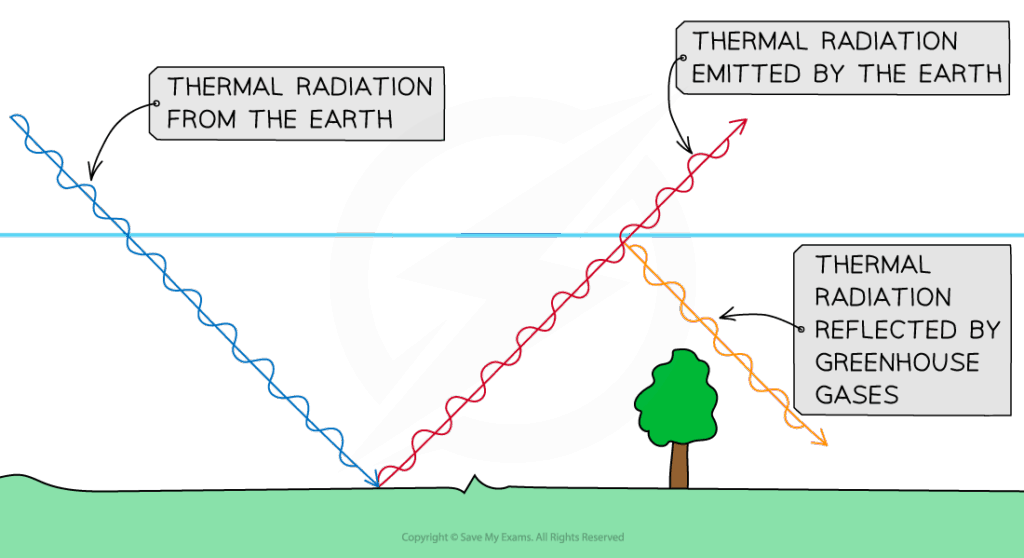

D4.3.1 EVIDENCE FOR CLIMATE CHANGE

📌Definition Table

Term Definition Climate change Long-term shifts in temperature, precipitation, and weather patterns driven by natural and anthropogenic factors. Greenhouse gases (GHGs) Gases like CO₂, CH₄, N₂O, and water vapour that trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere. Proxy data Indirect evidence (ice cores, tree rings, sediments) used to reconstruct past climate. Anthropogenic Human-induced changes to Earth systems, especially climate. Radiative forcing Difference between incoming solar radiation and outgoing infrared radiation, altered by GHGs. Feedback mechanisms Processes that amplify (positive feedback) or reduce (negative feedback) climate change effects. 📌Introduction

The reality of modern climate change is supported by multiple independent lines of evidence. Instrumental records show rising global temperatures, while proxy data demonstrate that current warming is unprecedented in recent millennia. Greenhouse gas concentrations have increased dramatically due to human activity since the Industrial Revolution, altering Earth’s energy balance. Evidence is strengthened by physical indicators such as melting glaciers, sea-level rise, and shifting weather patterns. Together, these show that anthropogenic climate change is real, measurable, and accelerating

📌 Instrumental and Proxy Evidence

- Instrumental records: consistent global temperature rise of ~1.1 °C since 1850.

- CO₂ monitoring (Keeling Curve): steady increase from ~280 ppm (pre-industrial) to >420 ppm today.

- Ice cores: trapped air bubbles reveal CO₂ and CH₄ fluctuations over 800,000 years; current levels exceed natural cycles.

- Tree rings & sediments: provide high-resolution records of past climates.

- Satellite data: confirm shrinking Arctic sea ice and changing albedo.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always mention both proxy and direct evidence to demonstrate a complete understanding of climate science data.

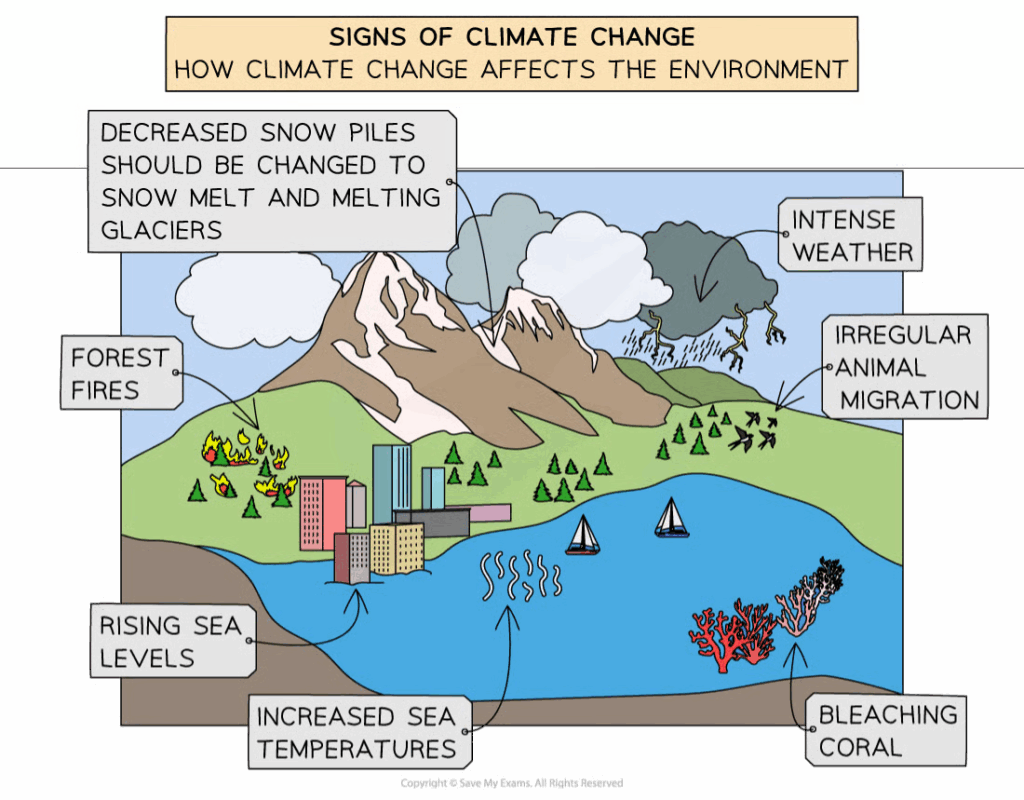

📌 Physical Indicators of Change

- Glacial retreat: mountain glaciers shrinking globally.

- Sea level rise: ~20 cm since 1900 due to thermal expansion + ice melt.

- Polar ice sheets: accelerating mass loss from Greenland and Antarctica.

- Ocean warming: >90% of excess heat absorbed by oceans.

- Extreme weather: increased frequency of heatwaves, droughts, and intense storms.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students can analyse publicly available climate datasets (e.g., NASA GISS temperature anomalies) to test hypotheses on warming trends.

📌 Greenhouse Effect and Radiative Forcing

- Natural greenhouse effect essential for life (~33 °C warmer).

- Enhanced greenhouse effect caused by anthropogenic GHG emissions.

- CO₂: fossil fuel combustion, deforestation.

- CH₄: agriculture, livestock, landfills.

- N₂O: fertilisers and industrial processes.

- Positive feedbacks: melting ice reduces albedo; thawing permafrost releases methane.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate reliability of proxy climate data (tree rings vs ice cores) or model radiative forcing impacts of different greenhouse gases.

📌 Consensus and Uncertainty

- 97% of climate scientists agree on anthropogenic warming.

- Models accurately reproduce observed warming only when human emissions are included.

- Uncertainty exists in predicting regional effects and feedback strength.

- Distinction between short-term variability (El Niño, volcanic eruptions) and long-term trends.

- Scientific consensus strengthens robustness of evidence.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could create awareness campaigns presenting local climate change evidence, e.g., rainfall shifts or heat records, linking global issues to local data.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Evidence for climate change underpins international agreements like the Paris Accord and informs policy on energy, transport, and conservation.

📌 Integration of Evidence

- Multiple independent indicators all point to anthropogenic warming.

- Robustness lies in convergence of datasets across disciplines.

- Evidence links atmospheric chemistry, physics, and ecology.

- Understanding past climates helps predict future trends.

- Strong basis for global action on climate change.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Climate models rely on proxies and simulations. TOK issue: How do we decide what counts as reliable evidence when direct observation over long timescales is impossible?

📝 Paper 2: Could involve interpreting graphs of CO₂ and temperature, explaining proxy evidence, or distinguishing natural vs anthropogenic drivers.

-

D4.2.3 EQUILIBRIUM AND EVOLUTIONARY CHANGE

📌Definition Table

Term Definition Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium Condition where allele and genotype frequencies remain constant in a population. Evolutionary change Alteration of allele frequencies across generations. Punctuated equilibrium Long periods of stasis interrupted by rapid evolutionary events. Gradualism Slow, steady accumulation of evolutionary changes. Stabilising selection Selection favouring intermediate phenotypes. Directional selection Selection favouring one extreme phenotype. 📌Introduction

Populations are not static: they evolve under selective pressures, genetic drift, gene flow, and mutation. However, in the absence of these forces, populations remain in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Evolutionary change can be gradual or punctuated, and selection can stabilise, diversify, or direct populations towards new adaptive peaks. These patterns provide a framework for understanding both microevolutionary changes and macroevolutionary trends in the fossil record

📌 Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

- States that allele frequencies remain constant if no evolutionary forces act.

- Assumptions: large population, random mating, no mutation, no migration, no selection.

- Provides a null model for studying evolution.

- Deviations reveal which evolutionary processes are at work.

- Useful in population genetics, epidemiology, and conservation biology.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Show ability to apply Hardy-Weinberg calculations. Simply defining it without calculation limits marks.

📌 Types of Natural Selection

- Stabilising selection: reduces variation, favours intermediate traits.

- Directional selection: shifts population towards one extreme (e.g., antibiotic resistance).

- Disruptive selection: favours both extremes, may lead to speciation.

- Balancing selection maintains multiple alleles (e.g., sickle-cell trait).

- Selection modes shape population equilibrium and change.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could collect data on variation in a measurable trait (e.g., seed size) and test if observed distribution fits stabilising or directional selection.

📌 Gradualism vs Punctuated Equilibrium

- Gradualism: Darwin’s view — small changes accumulate over long time.

- Punctuated equilibrium: Eldredge & Gould — long stasis interrupted by rapid speciation.

- Fossil record supports both: some lineages show stasis, others rapid bursts.

- Environmental shifts (mass extinctions, climate change) often trigger punctuation.

- Together, they reflect multiple evolutionary tempos.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could examine fossil evidence for tempo of evolution, e.g., comparing trilobite stasis vs mammalian radiation post-dinosaur extinction

📌 Microevolution and Macroevolution

- Microevolution: allele frequency shifts within populations.

- Macroevolution: large-scale patterns (speciation, extinction).

- Same processes drive both, but at different scales.

- Links population genetics with paleobiology.

- Demonstrates continuity of evolutionary theory.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could create interactive models showing Hardy-Weinberg dynamics or demonstrate selection types with real-life analogies for school outreach.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Hardy-Weinberg used in medical genetics (tracking allele frequencies in diseases), conservation (managing endangered species), and agriculture (maintaining crop diversity).

📌 Long-Term Evolutionary Dynamics

- Evolution is not linear but shaped by interactions of drift, selection, flow, mutation.

- Extinctions and radiations punctuate long-term patterns.

- Coevolution drives reciprocal adaptations.

- Evolutionary arms races explain rapid trait changes (predator-prey, host-pathogen).

- Stability and change are complementary features of evolution.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Models like Hardy-Weinberg and punctuated equilibrium simplify reality. TOK issue: How far can simplified models capture complex natural processes without distorting understanding?

📝 Paper 2: Questions may involve solving Hardy-Weinberg problems, analysing selection graphs, or evaluating gradualism vs punctuated equilibrium with examples.

-

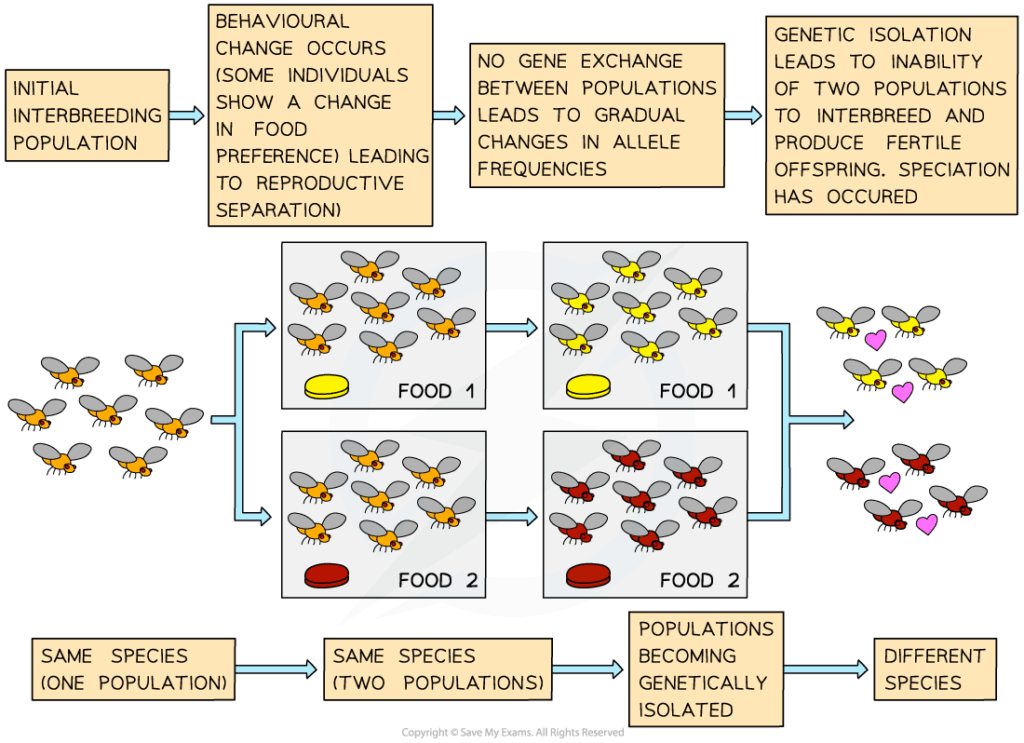

D4.2.2 SPECIATION AND ISOLATION MECHANISMS

📌Definition Table

Term Definition Speciation Formation of new species from existing populations. Allopatric speciation Speciation due to geographic isolation. Sympatric speciation Speciation within the same geographic area, often due to ecological or behavioural isolation. Prezygotic isolation Barriers preventing fertilisation (e.g., mating seasons, behavioural differences). Postzygotic isolation Barriers after fertilisation, such as hybrid sterility. Hybrid Offspring of two different species or populations, often sterile or less fit. 📌Introduction

Speciation explains how biodiversity arises. It occurs when populations of the same species become reproductively isolated and diverge genetically. Isolation can be geographic, ecological, behavioural, or genetic. Over time, accumulated differences prevent interbreeding, leading to new species. Understanding speciation mechanisms is critical for explaining adaptive radiation, biodiversity hotspots, and the tree of life

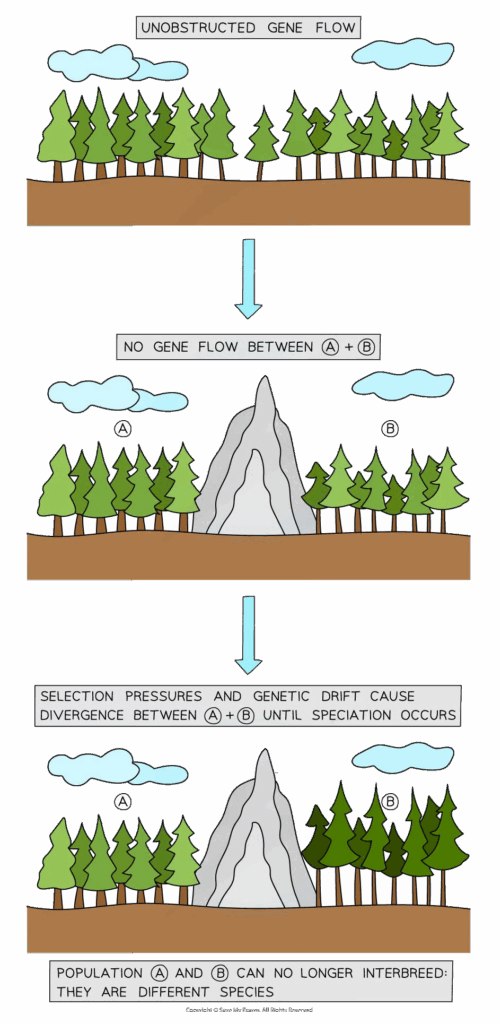

📌 Allopatric Speciation

- Most common form of speciation.

- Geographic isolation (mountains, rivers, islands) separates populations.

- Different environments impose different selective pressures.

- Drift and mutation accumulate independently.

- Reproductive isolation develops after sufficient divergence.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Don’t write “geographic isolation = speciation.” Explain the intermediate steps: isolation → divergence → reproductive isolation → new species.

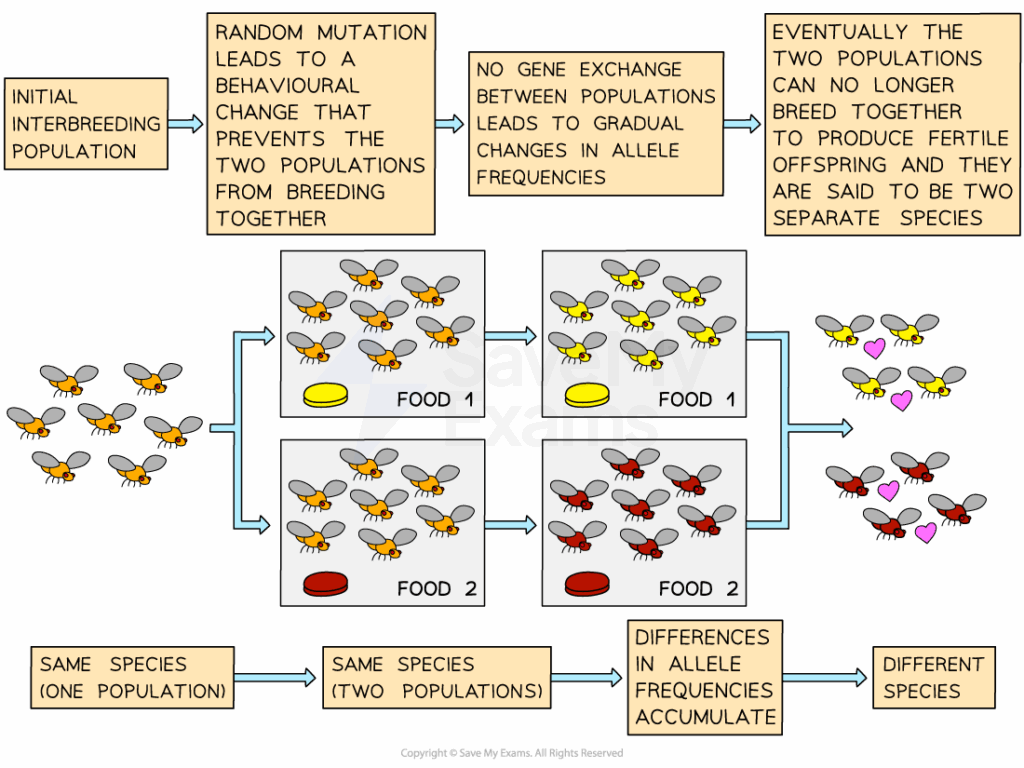

📌 Sympatric Speciation

- Occurs without physical barriers.

- Often due to ecological niches, e.g., insects specialising on different host plants.

- Behavioural isolation: changes in mating calls, timing, or rituals.

- Polyploidy in plants: sudden speciation through genome duplication.

- Demonstrates that speciation can occur even with gene flow, if selection is strong.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could model isolation using populations of model organisms (fruit flies, yeast) exposed to different conditions and track divergence.

.📌 Isolation Mechanisms

- Prezygotic barriers: temporal (different mating seasons), behavioural (mating calls), mechanical (incompatible structures).

- Postzygotic barriers: hybrid inviability, hybrid sterility (e.g., mule), reduced hybrid fitness.

- Reinforcement strengthens isolation by favouring avoidance of maladaptive hybridisation.

- Essential in preventing gene flow once divergence has started.

- Maintain distinct species boundaries in sympatric regions.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could compare speciation models (allopatric vs sympatric) using case studies such as cichlid fish, Galápagos finches, or African Rift Valley lakes.

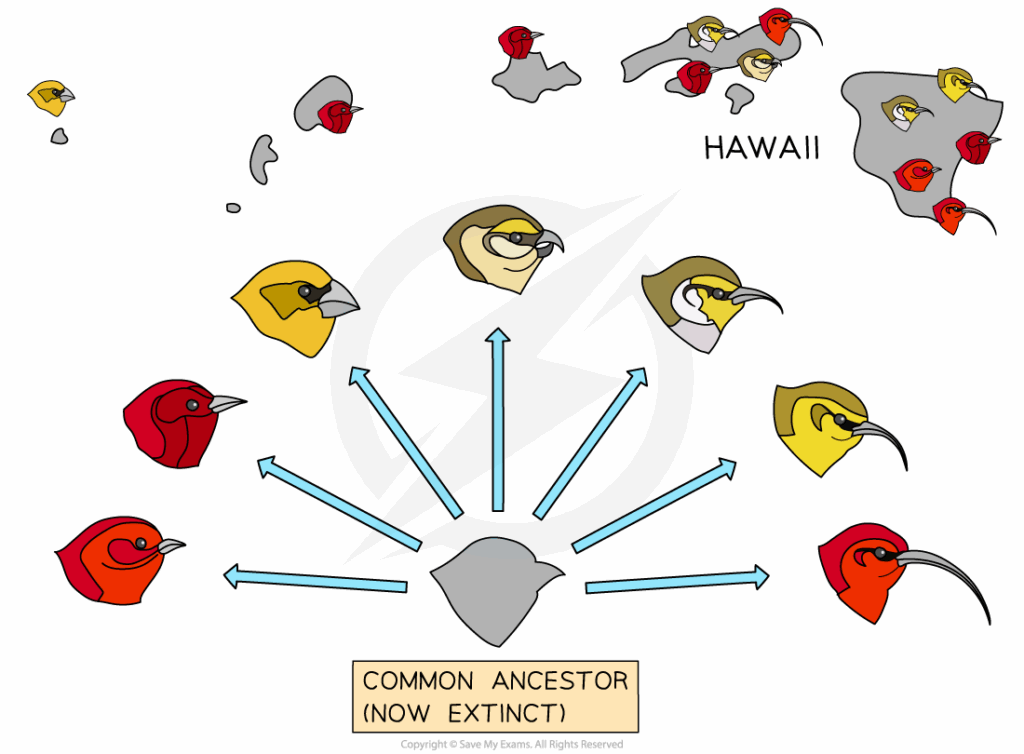

📌 Adaptive Radiation

- Rapid speciation when organisms colonise new environments.

- Classic examples: Darwin’s finches, Hawaiian honeycreepers.

- Driven by ecological opportunities and niche differentiation.

- Produces high biodiversity in island ecosystems.

- Demonstrates power of speciation in generating diversity.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design posters or presentations on local endemic species and their speciation histories, raising awareness of biodiversity conservation.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Speciation studies inform conservation strategies, especially for endangered species management and biodiversity preservation. They also guide agriculture (e.g., polyploid crops).

📌 Patterns of Speciation

- Gradualism: slow, continuous accumulation of changes.

- Punctuated equilibrium: long stability interrupted by rapid bursts of change.

- Both models supported by fossil evidence.

- Different taxa may follow different patterns.

- Together, they illustrate flexibility of evolutionary tempo.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Species boundaries are not always clear-cut. TOK issue: How do scientists deal with concepts (like “species”) that have fuzzy, debated definitions?

📝 Paper 2: Questions could involve explaining types of speciation, describing isolation mechanisms, or applying models to given case studies.

-

D4.2.1 GENETIC DRIFT AND GENE FLOW

📌Definition Table

Term Definition Genetic drift Random change in allele frequencies in a population due to chance events, especially in small populations. Bottleneck effect Genetic drift caused by a drastic reduction in population size, leading to reduced genetic diversity. Founder effect Genetic drift occurring when a small group of individuals colonises a new habitat, carrying only part of the original genetic variation. Gene flow Movement of alleles between populations through migration of individuals or gametes. Allele frequency Proportion of a specific allele within a population’s gene pool. Genetic diversity Variety of alleles and genotypes within a population. 📌Introduction

Population genetics studies how allele frequencies change over time, shaping evolution. Two important mechanisms beyond natural selection are genetic drift and gene flow. Genetic drift is driven by random chance, often reducing genetic variation in small populations. Gene flow, in contrast, introduces new alleles into a population, often increasing diversity and counteracting drift. Together, they influence whether populations diverge or remain genetically connected, making them central to understanding evolutionary dynamics.

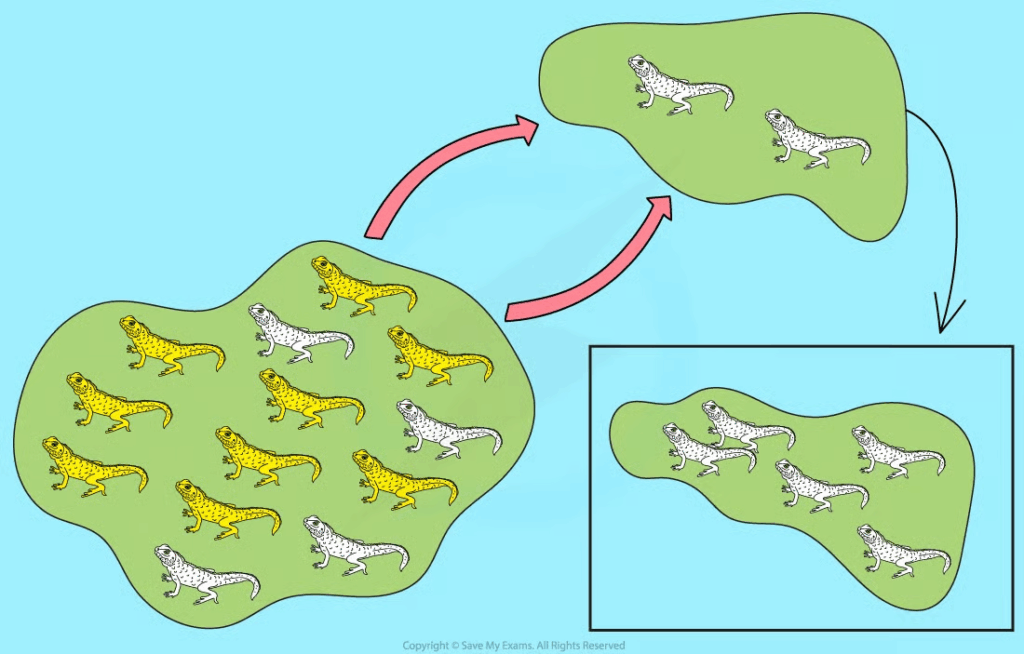

📌 Genetic Drift: Random Changes in Small Populations

- Drift has a stronger effect in small populations, where chance events alter allele frequencies significantly.

- The bottleneck effect reduces genetic diversity after catastrophic events like disease, natural disasters, or overhunting.

- The founder effect occurs when a few individuals establish a new population, often carrying unrepresentative alleles.

- Drift can lead to fixation (allele frequency reaches 100%) or loss of alleles.

- Unlike natural selection, drift does not favour advantageous traits — changes are random.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Don’t confuse genetic drift with natural selection. Drift is random, while selection is non-random and driven by fitness advantages.

📌 Gene Flow: Movement of Alleles Between Populations

- Occurs when individuals migrate between populations and interbreed.

- Maintains genetic connectivity between populations.

- Can increase genetic diversity by introducing new alleles.

- May counteract effects of drift by reintroducing lost alleles.

- Too much gene flow can reduce local adaptation, while limited flow promotes divergence.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: A class experiment could simulate genetic drift using coloured beads to represent alleles in small vs large populations, or gene flow using exchange between groups.

📌 Interaction Between Drift and Flow

- Drift reduces diversity; gene flow replenishes it.

- Isolated populations with little flow diverge genetically, sometimes leading to speciation.

- Conservation biology emphasises gene flow corridors to maintain diversity in endangered species.

- Balance between drift and flow shapes population stability and adaptation.

- Human migration patterns provide strong real-world examples of gene flow.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could explore whether gene flow prevents or promotes speciation in fragmented habitats, combining molecular data with ecological theory.

📌 Case Studies

- Cheetah bottleneck: extremely low diversity due to past population collapse.

- Island colonisation: founder effects in island bird populations.

- Human gene flow: interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals.

- Conservation corridors: tiger reserves connected by wildlife corridors reduce drift effects.

- Drift explains some allele frequency patterns where selection pressure is absent.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could simulate genetic drift with classroom role-play or model migration with exchange games, then present results to peers to show random vs directed processes.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Understanding drift and flow is crucial for conservation genetics, disease resistance, agriculture (crop gene banks), and tracking human evolutionary history.

📌 Population Genetics Framework

- Hardy-Weinberg principle provides a baseline of no drift, no flow, no selection.

- Deviations indicate evolutionary processes.

- Drift and flow must be considered alongside mutation and selection.

- Genetic data allows tracking of these processes in real time.

- These mechanisms are essential for predicting population responses to change.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Genetic drift challenges the notion that evolution is always adaptive. TOK issue: To what extent do random processes undermine deterministic explanations in science?

📝 Paper 2: Expect tasks involving allele frequency changes, bottleneck/founder scenarios, or predicting effects of gene flow between populations.