| Content | Guidance, clarification and syllabus links |

|---|---|

|

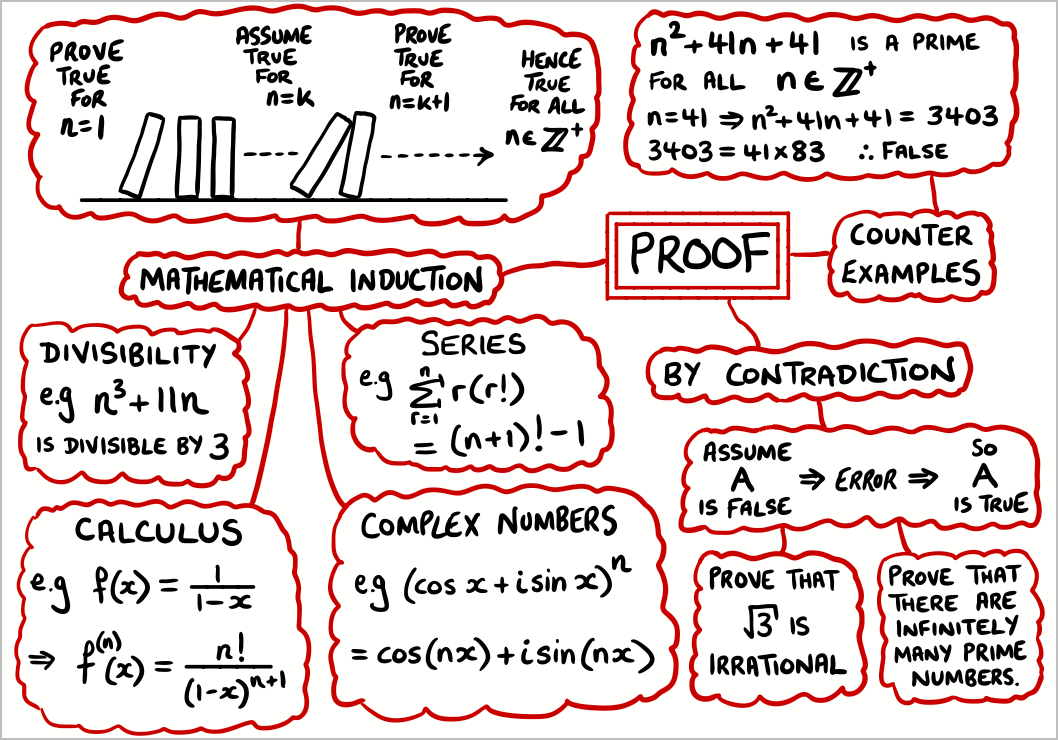

Proof by mathematical induction for statements involving natural numbers.

Strong (complete) induction and well-ordering principle. Proof by contradiction (reductio ad absurdum). Counterexamples to disprove mathematical statements. Direct proof methods and logical reasoning. Proof techniques for divisibility and inequalities. Applications to sequences, series, and combinatorics. |

Essential foundation for advanced mathematical reasoning.

Emphasis on rigorous logical structure and clear exposition. Connection to other AHL topics: sequences, complex numbers, combinatorics. Development of mathematical maturity and proof-writing skills. Preparation for university-level mathematics and formal logic. Historical context: foundations of mathematical logic. Applications in computer science: algorithms, recursion, program correctness. Critical thinking and analytical reasoning development. |

📌 Introduction

Mathematical proof represents the cornerstone of rigorous mathematical reasoning, distinguishing mathematics from empirical sciences through its demand for absolute logical certainty. The art and science of proof encompasses multiple sophisticated techniques—induction, contradiction, and counterexample—each serving distinct but complementary roles in establishing mathematical truth. These methods transcend mere computational procedures, embodying the essence of mathematical thinking that transforms observation into understanding, conjecture into theorem, and intuition into irrefutable logical argument.

The study of proof techniques at the AHL level serves dual purposes: developing the analytical skills necessary for advanced mathematical study while fostering the logical reasoning capabilities essential for success across diverse academic and professional domains. Mathematical induction provides a powerful framework for establishing patterns that extend infinitely, proof by contradiction reveals truth through the impossibility of falsehood, and counterexamples demonstrate the critical importance of precision in mathematical statements. Together, these techniques form an intellectual toolkit that enables students to engage with mathematics not merely as consumers of established results, but as active participants in the ongoing process of mathematical discovery and verification.

📌 Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Mathematical Induction |

Proof technique for statements about natural numbers using: 1) Base case verification 2) Inductive step assumption → conclusion |

| Base Case |

Initial verification that the statement holds for the smallest value (usually \(n = 1\) or \(n = 0\)) in the domain of interest |

| Inductive Hypothesis |

Assumption that the statement is true for some arbitrary \(n = k\) where \(k \geq\) base case value |

| Inductive Step |

Logical proof that if the statement is true for \(n = k\), then it must also be true for \(n = k + 1\) |

| Strong Induction |

Variant where inductive hypothesis assumes truth for all values from base case up to and including \(n = k\) |

| Proof by Contradiction |

Method assuming the negation of the desired conclusion and deriving a logical contradiction (reductio ad absurdum) |

| Counterexample |

Specific example that demonstrates the falsity of a universal statement or mathematical conjecture |

| Direct Proof |

Straightforward logical argument from hypotheses to conclusion using established mathematical principles |

| Well-Ordering Principle |

Every non-empty set of positive integers has a smallest element (foundation for inductive reasoning) |

📌 Properties & Key Principles

- Induction Structure: Base case + Inductive step = Universal validity

- Logical Equivalence: Induction ≡ Well-ordering principle ≡ Strong induction

- Contradiction Method: \(\neg P \rightarrow \text{contradiction} \Rightarrow P\) is true

- Counterexample Power: Single example disproves universal statement

- Proof Hierarchy: Existence < Construction < Uniqueness < Optimality

- Logic Principles: Modus ponens, modus tollens, syllogism

- Divisibility Rules: \(a|b \wedge a|c \Rightarrow a|(bx + cy)\) for integers \(x, y\)

- Inequality Techniques: Transitivity, addition/multiplication preservation

Mathematical Induction Template:

Step 1: Base Case

Verify P(n₀) is true by direct calculation or substitution.

Step 2: Inductive Hypothesis

Assume P(k) is true for some arbitrary k ≥ n₀.

State explicitly what this assumption means.

Step 3: Inductive Step

Using the assumption P(k), prove that P(k+1) must be true.

Show the logical connection: P(k) → P(k+1).

Step 4: Conclusion

By mathematical induction, P(n) is true for all n ≥ n₀.

Proof by Contradiction Template:

Step 1: Assume Negation

Assume ¬P (the opposite of what you want to prove).

Step 2: Derive Consequences

Use logical reasoning and known facts to derive

implications from the assumption ¬P.

Step 3: Find Contradiction

Show that the assumption leads to a statement that is

both true and false (or contradicts known facts).

Step 4: Conclude

Since ¬P leads to contradiction, P must be true.

Remember: The inductive step is the heart of the proof – it must be logically rigorous and complete.

📌 Common Mistakes & How to Avoid Them

Wrong: “For \(n = 1\), the formula works” (without showing work)

Right: “For \(n = 1\): LHS = \(1^2 = 1\), RHS = \(\frac{1(1+1)(2(1)+1)}{6} = 1\). ✓”

How to avoid: Always show complete algebraic verification for the base case.

Wrong: Assuming \(P(k+1)\) to prove \(P(k+1)\)

Right: Using only \(P(k)\) and known facts to establish \(P(k+1)\)

How to avoid: Clearly distinguish what you assume (inductive hypothesis) from what you need to prove.

Wrong: Showing an unusual result and calling it a contradiction

Right: Deriving a statement that contradicts basic logic or established facts

How to avoid: Ensure your contradiction is genuinely impossible, not just unexpected.

Wrong: “The statement is false” (without providing specific example)

Right: “For \(n = 2\): \(2^2 = 4\) but \(2^3 = 8\), so \(n^2 \neq n^3\) in general.”

How to avoid: Always provide explicit numerical verification of your counterexample.

Wrong: “Assume the formula works for some \(k\)”

Right: “Assume \(1^2 + 2^2 + \cdots + k^2 = \frac{k(k+1)(2k+1)}{6}\) for some \(k \geq 1\)”

How to avoid: State the inductive hypothesis as a complete, specific mathematical statement.

📌 Calculator Skills: Casio CG-50 & TI-84

Sequence and Series Verification:

1. Use [MENU] → [Statistics] → [List] for sequence calculations

2. Enter recursive formulas using [OPTN] → [CALC] → [Σ]

3. Generate terms to verify base cases and patterns

4. Use [SHIFT] + [7] for summation calculations

Inequality Testing:

1. Graph functions to visualize inequality relationships

2. Use [TABLE] function to check multiple values

3. [SHIFT] + [F5] for numerical integration verification

4. Store variables for systematic testing

Divisibility Checking:

1. Use MOD function: [OPTN] → [NUM] → [MOD]

2. Test divisibility patterns systematically

3. Program loops for pattern verification

4. Use [PROGRAM] mode for automated checking

Counterexample Generation:

1. Systematic value testing using loops

2. Random number generation for testing

3. Graphical analysis for function properties

4. Statistical analysis for pattern detection

Induction Support:

1. [STAT] → [EDIT] for sequence generation

2. Use seq() function for pattern testing

3. [2nd] [LIST] → [MATH] for sum() calculations

4. [MATH] → [NUM] for remainder calculations

Pattern Recognition:

1. Graph sequences using [Y=] editor

2. [2nd] [TBLSET] for systematic value checking

3. [STAT] → [CALC] for regression analysis

4. Use scatter plots for visual pattern detection

Proof Verification:

1. Program custom functions for repeated calculations

2. Use [MATH] → [NUM] → [mod] for modular arithmetic

3. [2nd] [TEST] for logical comparisons

4. Store and recall values for systematic testing

Advanced Applications:

1. Matrix operations for linear proof applications

2. Complex number verification for algebraic proofs

3. Statistical functions for probabilistic arguments

4. Graphical analysis for geometric proofs

Systematic Approach:

• Use calculators for computational verification, not proof construction

• Generate examples and counterexamples systematically

• Verify algebraic manipulations with numerical checks

• Test boundary cases and special values

Pattern Discovery:

• Generate sequences to identify patterns before proving

• Use graphical analysis to visualize mathematical relationships

• Statistical analysis can suggest proof directions

• Programming helps automate repetitive verification tasks

Verification Techniques:

• Always verify base cases computationally

• Check inductive step logic with specific examples

• Use technology to explore variations and extensions

• Generate counterexamples for false statements systematically

📌 Mind Map

📌 Applications in Science and IB Math

- Computer Science: Algorithm correctness, recursive program verification, complexity analysis

- Cryptography: Security protocol verification, prime number theory, modular arithmetic

- Physics: Conservation laws, symmetry principles, quantum mechanical proofs

- Economics: Game theory proofs, optimization verification, equilibrium existence

- Engineering: System stability proofs, reliability analysis, design verification

- Pure Mathematics: Number theory, algebra, analysis, topology foundations

- Statistics: Convergence proofs, distribution properties, estimation theory

- Logic and Philosophy: Formal reasoning, philosophical argumentation, epistemology

Excellent IA Topics:

• Mathematical induction applications: proving sequences, series, and combinatorial identities

• Proof by contradiction in number theory: irrationality proofs and prime number investigations

• Counterexamples in mathematics: famous conjectures and their refutations

• Logic and reasoning: formal proof systems and mathematical foundations

• Computer science applications: algorithm verification and program correctness

• Cryptographic security: proof techniques in modern encryption systems

• Game theory analysis: equilibrium existence and strategy optimization

• Historical investigations: famous proofs and their mathematical impact

IA Structure Tips:

• Begin with clear motivation: why are rigorous proofs essential?

• Establish theoretical foundations: logical principles and proof techniques

• Include substantial applications with concrete examples and calculations

• Demonstrate both proof construction and proof verification

• Connect to multiple mathematical areas: algebra, analysis, number theory

• Use technology appropriately for computation and verification

• Explore both successful proofs and instructive failed attempts

• Address philosophical aspects: what makes a proof convincing?

• Include original investigation or novel application of proof techniques

• Connect to advanced topics: formal logic, set theory, mathematical foundations

📌 Worked Examples (IB Style)

Q1. Prove by mathematical induction that \(1 + 3 + 5 + \cdots + (2n-1) = n^2\) for all \(n \geq 1\).

Solution:

Step 1: Base Case (\(n = 1\))

LHS: \(2(1) – 1 = 1\)

RHS: \(1^2 = 1\)

Since LHS = RHS, the base case holds. ✓

Step 2: Inductive Hypothesis

Assume that for some \(k \geq 1\):

\(1 + 3 + 5 + \cdots + (2k-1) = k^2\)

Step 3: Inductive Step

We need to prove: \(1 + 3 + 5 + \cdots + (2k-1) + (2(k+1)-1) = (k+1)^2\)

LHS = \([1 + 3 + 5 + \cdots + (2k-1)] + (2k+1)\)

= \(k^2 + (2k+1)\) (by inductive hypothesis)

= \(k^2 + 2k + 1\)

= \((k+1)^2\) = RHS ✓

Step 4: Conclusion

By mathematical induction, the formula holds for all \(n \geq 1\).

✅ Proven by mathematical induction

Q2. Prove by contradiction that \(\sqrt{2}\) is irrational.

Solution:

Step 1: Assume the Negation

Assume \(\sqrt{2}\) is rational. Then \(\sqrt{2} = \frac{p}{q}\) where \(p, q\) are integers with \(q \neq 0\) and \(\gcd(p,q) = 1\) (fraction in lowest terms).

Step 2: Derive Consequences

Squaring both sides: \(2 = \frac{p^2}{q^2}\)

Multiply by \(q^2\): \(2q^2 = p^2\)

This means \(p^2\) is even, so \(p\) must be even.

Step 3: Continue the Analysis

Since \(p\) is even, let \(p = 2k\) for some integer \(k\).

Substituting: \(2q^2 = (2k)^2 = 4k^2\)

Dividing by 2: \(q^2 = 2k^2\)

This means \(q^2\) is even, so \(q\) must be even.

Step 4: Find the Contradiction

Both \(p\) and \(q\) are even, which means \(\gcd(p,q) \geq 2\).

This contradicts our assumption that \(\gcd(p,q) = 1\).

Step 5: Conclusion

Since the assumption leads to a contradiction, \(\sqrt{2}\) must be irrational.

✅ Proven by contradiction

Q3. Prove by induction that \(n! > 2^n\) for all \(n \geq 4\).

Solution:

Step 1: Base Case (\(n = 4\))

LHS: \(4! = 24\)

RHS: \(2^4 = 16\)

Since \(24 > 16\), the base case holds. ✓

Step 2: Inductive Hypothesis

Assume that for some \(k \geq 4\): \(k! > 2^k\)

Step 3: Inductive Step

We need to prove: \((k+1)! > 2^{k+1}\)

LHS: \((k+1)! = (k+1) \cdot k!\)

\(> (k+1) \cdot 2^k\) (by inductive hypothesis)

Since \(k \geq 4\), we have \(k+1 \geq 5 > 2\), so:

\((k+1) \cdot 2^k > 2 \cdot 2^k = 2^{k+1}\)

Therefore: \((k+1)! > 2^{k+1}\) ✓

Step 4: Conclusion

By mathematical induction, \(n! > 2^n\) for all \(n \geq 4\).

✅ Proven by mathematical induction

Q4. Disprove: “For all positive integers \(n\), \(n^2 – n + 41\) is prime.”

Solution:

Method: Counterexample

We need to find a positive integer \(n\) such that \(n^2 – n + 41\) is composite.

Strategy:

Let’s try \(n = 41\):

\(n^2 – n + 41 = 41^2 – 41 + 41 = 41^2 = 1681\)

Verification:

\(1681 = 41 \times 41\)

Since \(1681\) has factors other than 1 and itself, it is composite.

Alternative counterexample:

For \(n = 40\): \(40^2 – 40 + 41 = 1600 – 40 + 41 = 1601 = 41 \times 39\)

✅ Statement disproven by counterexample: \(n = 41\)

Q5. Prove that for all integers \(n \geq 1\), \(3\) divides \(n^3 – n\).

Solution:

Step 1: Factor the Expression

\(n^3 – n = n(n^2 – 1) = n(n-1)(n+1)\)

This is the product of three consecutive integers.

Step 2: Divisibility Analysis

Among any three consecutive integers, exactly one is divisible by 3.

Therefore, their product is divisible by 3.

Alternative Proof by Cases:

Consider \(n \pmod{3}\):

• If \(n \equiv 0 \pmod{3}\): then \(3|n\), so \(3|(n^3-n)\)

• If \(n \equiv 1 \pmod{3}\): then \(n-1 \equiv 0 \pmod{3}\), so \(3|(n-1)\), hence \(3|(n^3-n)\)

• If \(n \equiv 2 \pmod{3}\): then \(n+1 \equiv 0 \pmod{3}\), so \(3|(n+1)\), hence \(3|(n^3-n)\)

Conclusion:

In all cases, \(3\) divides \(n^3 – n\).

✅ Proven using divisibility properties

Key strategies for success:

• Plan your proof strategy before writing

• Use clear mathematical language and notation

• State the inductive hypothesis precisely

• Show all algebraic manipulation in the inductive step

• For contradiction proofs, clearly identify the contradiction

• Verify counterexamples with complete calculations

📌 Multiple Choice Questions (with Detailed Solutions)

Q1. Which statement about mathematical induction is correct?

A) The base case is sufficient to prove the statement

B) The inductive step alone proves the statement

C) Both base case and inductive step are necessary

D) Only the inductive hypothesis is needed

📖 Show Answer

Solution:

Mathematical induction requires both components:

• Base case: establishes the statement for the initial value

• Inductive step: shows the logical chain from k to k+1

Without either component, the proof is incomplete.

✅ Answer: C) Both base case and inductive step are necessary

Q2. A counterexample to the statement “All prime numbers are odd” is:

A) 3 B) 2 C) 9 D) 15

📖 Show Answer

Solution:

To disprove “All prime numbers are odd,” we need a prime number that is even.

• 2 is prime (only divisible by 1 and 2) and even

• 3 is prime and odd (supports the statement)

• 9 and 15 are not prime

✅ Answer: B) 2

Q3. In a proof by contradiction, we assume:

A) The statement we want to prove

B) The negation of what we want to prove

C) A related but different statement

D) The conclusion follows from the premises

📖 Show Answer

Solution:

Proof by contradiction (reductio ad absurdum) works by:

1. Assuming the opposite of what we want to prove

2. Deriving a logical contradiction

3. Concluding the original statement must be true

✅ Answer: B) The negation of what we want to prove

📌 Short Answer Questions (with Detailed Solutions)

Q1. Prove by induction that \(1 + 2 + 3 + \cdots + n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}\).

📖 Show Answer

Complete solution:

Base case (n = 1):

LHS: \(1\), RHS: \(\frac{1(1+1)}{2} = 1\) ✓

Inductive hypothesis:

Assume \(1 + 2 + \cdots + k = \frac{k(k+1)}{2}\)

Inductive step:

\(1 + 2 + \cdots + k + (k+1) = \frac{k(k+1)}{2} + (k+1)\)

\(= \frac{k(k+1) + 2(k+1)}{2} = \frac{(k+1)(k+2)}{2}\) ✓

✅ Proven by mathematical induction

Q2. Find a counterexample to: “For all real numbers \(x\), \(x^2 > x\).”

📖 Show Answer

Complete solution:

Analysis:

We need \(x\) such that \(x^2 \leq x\)

Rearranging: \(x^2 – x \leq 0\) or \(x(x-1) \leq 0\)

Counterexamples:

• \(x = 0\): \(0^2 = 0 \not> 0\)

• \(x = 0.5\): \((0.5)^2 = 0.25 < 0.5\)

• \(x = 1\): \(1^2 = 1 \not> 1\)

✅ Any \(x \in [0,1]\) serves as a counterexample

📌 Extended Response Questions (with Full Solutions)

Q1. Consider the sequence defined by \(a_1 = 1\), \(a_2 = 3\), and \(a_n = 3a_{n-1} – 2a_{n-2}\) for \(n \geq 3\).

(a) Find the first six terms of the sequence. [2 marks]

(b) Conjecture a formula for \(a_n\) and prove it using mathematical induction. [8 marks]

(c) Use your formula to find \(a_{10}\). [2 marks]

📖 Show Answer

Complete solution:

(a) First six terms:

\(a_1 = 1\), \(a_2 = 3\)

\(a_3 = 3(3) – 2(1) = 7\)

\(a_4 = 3(7) – 2(3) = 15\)

\(a_5 = 3(15) – 2(7) = 31\)

\(a_6 = 3(31) – 2(15) = 63\)

(b) Conjecture and proof:

Pattern observation: \(1, 3, 7, 15, 31, 63\) suggests \(a_n = 2^n – 1\)

Proof by strong induction:

Base cases: \(a_1 = 1 = 2^1 – 1\) ✓, \(a_2 = 3 = 2^2 – 1\) ✓

Inductive hypothesis: \(a_j = 2^j – 1\) for all \(j \leq k\)

Inductive step: \(a_{k+1} = 3a_k – 2a_{k-1}\)

\(= 3(2^k – 1) – 2(2^{k-1} – 1)\)

\(= 3 \cdot 2^k – 3 – 2^k + 2 = 2 \cdot 2^k – 1 = 2^{k+1} – 1\) ✓

(c) Using the formula:

\(a_{10} = 2^{10} – 1 = 1024 – 1 = 1023\)

✅ Final Answers:

(a) \(1, 3, 7, 15, 31, 63\)

(b) \(a_n = 2^n – 1\) (proven by induction)

(c) \(a_{10} = 1023\)