A2.3.1 – VIRUS STRUCTURE

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Virus | A non-cellular infectious particle composed of genetic material enclosed in a protein coat; considered acellular as they lack metabolism. |

| Capsid | Protein coat surrounding viral genetic material, often with attachment proteins for host cell recognition. |

| Envelope | Lipid bilayer surrounding some viruses, derived from host cell membranes, often containing glycoproteins. |

| Attachment Proteins | Molecules on the viral surface that bind to specific receptors on host cells. |

| Retrovirus | RNA virus (e.g., HIV) that uses reverse transcriptase to produce DNA from its RNA genome. |

📌Introduction

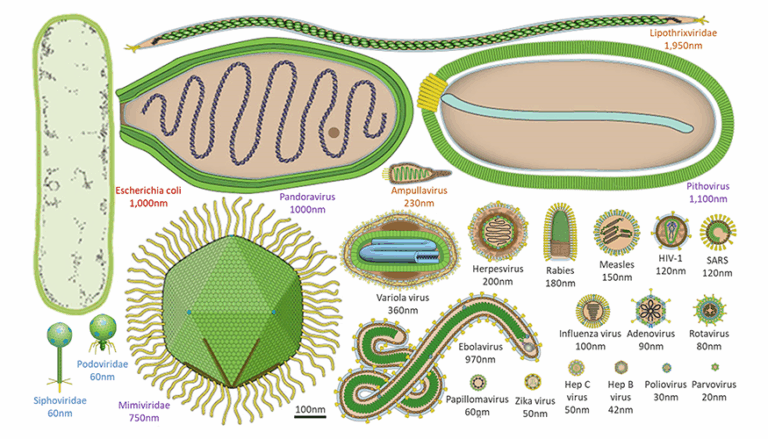

Viruses are acellular infectious agents that occupy a unique position in biology — they are not considered living organisms because they lack cellular structures, metabolism, and independent reproduction. Instead, they hijack the machinery of host cells to replicate. They are extremely small, with sizes typically between 20–300 nm, visible only under an electron microscope. Despite their simplicity, viruses exhibit remarkable diversity in shape, genetic material, and infection strategies. Their ability to infect nearly all forms of life makes them central to studies in medicine, genetics, and evolutionary biology.

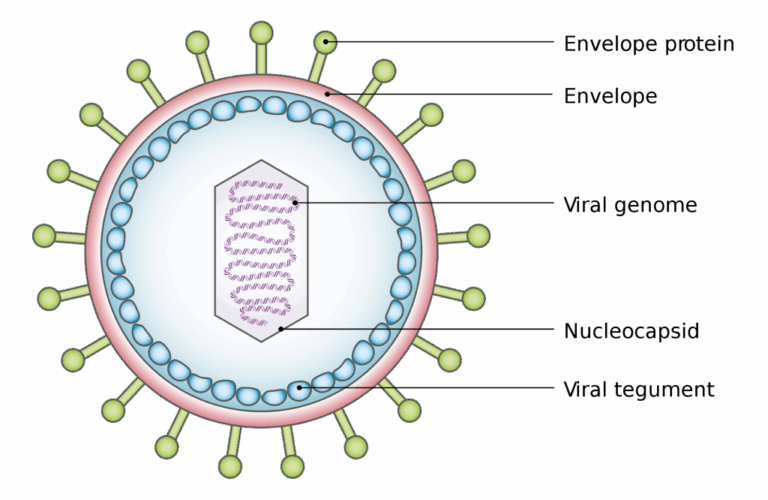

📌 General Structure of Viruses

- All viruses have a nucleic acid genome made of DNA or RNA, which may be single- or double-stranded, linear or circular.

- The genome is enclosed in a capsid made of protein subunits (capsomeres).

- Attachment proteins on the capsid or envelope bind specifically to host cell receptors.

- Many animal viruses have a lipid envelope derived from the host cell membrane; some plant and bacteriophage viruses are non-enveloped.

- Viruses have no cytoplasm, organelles, or metabolic enzymes (or very few).

- They are parasitic, relying entirely on the host cell’s ribosomes and energy for replication.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always specify the type of nucleic acid and whether the virus is enveloped when describing its structure — IB markschemes reward these details.

📌 Structural Diversity

- Genetic material can be RNA or DNA, single- or double-stranded.

- Shapes include helical, polyhedral, complex, and spherical.

- Host range is determined by specific attachment proteins — e.g., HIV targets helper T cells, hepatitis viruses target liver cells.

- Bacteriophage lambda: infects E. coli, has dsDNA, capsid head, tail, and tail fibres for DNA injection.

- Coronavirus: ssRNA, spherical, envelope with spike glycoproteins forming a “crown” appearance.

- HIV: retrovirus with two RNA strands, reverse transcriptase, protein capsid, and envelope from host cell membrane.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: For a practical investigation, model virus structures using 3D printing or software, emphasising differences between enveloped and non-enveloped viruses.

📌 Special Features in Some Viruses

- Enzymes such as reverse transcriptase (in retroviruses) or lysozyme (in bacteriophages).

- Tail fibres in bacteriophages for host recognition.

- Glycoproteins for immune evasion and host entry.

- Segmented genomes in some viruses (e.g., influenza), allowing genetic reassortment.

- Capsid symmetry (icosahedral, helical, complex) influences stability and infectivity.

- Envelope proteins can determine virus transmissibility.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate structural adaptations in viruses that enable cross-species transmission, such as changes in surface glycoproteins.

📌 Functional Importance of Structure

- Capsid protects viral genome from degradation.

- Attachment proteins ensure host specificity.

- Envelope lipids aid entry into host cells via membrane fusion.

- Genome type influences replication strategy (RNA viruses often mutate faster).

- Structural variation determines environmental stability (non-enveloped viruses survive longer outside hosts).

- Viral structure can influence immune system evasion strategies.

❤️ CAS Link: A CAS project could involve creating educational campaigns on viral structure and transmission prevention during flu season.

📌 Microscopy in Virus Study

- Electron microscopy is required due to small size.

- TEM reveals internal viral structures, capsid arrangement, and genome location.

- SEM provides 3D images of virus surface morphology.

- Cryo-electron microscopy enables near-atomic resolution structural analysis.

- Structural knowledge is critical for vaccine design.

- Light microscopy cannot resolve individual viruses due to resolution limits (~200 nm).

🔍 TOK Perspective: The study of viruses illustrates how limitations in technology constrain what we can know — before electron microscopy, viruses were only hypothesised based on disease patterns.

🌍 Real-World Connection:

Understanding viral structure underpins vaccine development and antiviral drug design, such as targeting HIV’s reverse transcriptase or influenza’s surface proteins.