B4.2.2 – INTERACTIONS AND NICHE DIFFERENTIATION

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Interspecific Competition | Interaction where individuals of different species compete for the same limited resource, negatively affecting both. |

| Predation | Biological interaction where one organism (predator) kills and consumes another (prey). |

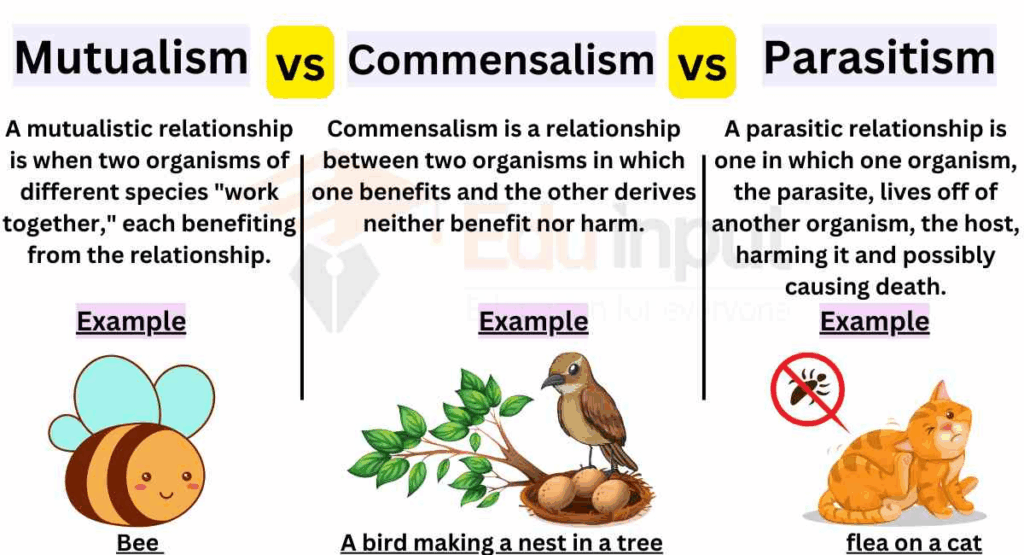

| Mutualism | Symbiotic relationship where both species benefit. |

| Commensalism | Symbiotic relationship where one species benefits and the other is neither helped nor harmed. |

| Amensalism | Relationship where one species is harmed and the other is unaffected. |

📌Introduction

Species do not live in isolation — they interact constantly with others in their ecosystem. These interactions shape ecological niches, influencing where species live, what they eat, and how they reproduce. Competition tends to narrow realised niches, while facilitative interactions like mutualism can expand them. Understanding these dynamics is essential for conservation biology and for predicting how ecosystems respond to environmental change.

❤️ CAS Link: Lead a school garden project where native plants are selected to promote beneficial interactions with pollinators and other species.

📌 Interspecific Competition

- Occurs when two or more species require the same limited resource (e.g., food, nesting sites, light).

- Reduces population growth rates for all competitors involved.

- May result in competitive exclusion (one species outcompetes the other) or resource partitioning (niche differentiation).

- Example: Different grass species competing for light and nutrients in a meadow.

- Can drive evolutionary change, selecting traits that reduce overlap in resource use.

🧠 Examiner Tip: When describing competition, always specify the resource in question and whether the competition is exploitative (indirect) or interference (direct).

📌 Predation and Herbivory

- Predation controls prey populations, preventing overpopulation and resource depletion.

- Can drive prey adaptations such as camouflage, mimicry, and defensive behaviours.

- Herbivory is a specialised form where herbivores feed on plants; plants may evolve spines, toxins, or rapid regrowth as defences.

- Predation pressure can create “landscape of fear” effects, altering prey behaviour and habitat use.

- Example: Sea otters preying on sea urchins regulates kelp forest health.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone restored balance by reducing elk overgrazing, allowing vegetation recovery.

📌 Mutualism and Commensalism

- Mutualism benefits both partners — e.g., bees and flowering plants; coral and zooxanthellae.

- Can be obligate (partners cannot survive without each other) or facultative (beneficial but not essential).

- Commensalism benefits one partner without affecting the other — e.g., barnacles on whales gain transport to nutrient-rich waters.

- Such relationships can increase survival, reproduction, and niche breadth for one or both species.

- May shift along a spectrum over time, becoming parasitic or competitive depending on conditions.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Labelling interactions as “beneficial” or “harmful” is human interpretation — in nature, these roles can change depending on environmental context.

📌 Niche Differentiation Outcomes

- Over evolutionary time, species under strong competition adapt to minimise niche overlap.

- Morphological differentiation — e.g., variation in beak shape among finches reduces competition for seed types.

- Temporal separation — nocturnal vs. diurnal foragers avoid direct competition.

- Habitat segregation — warbler species feeding in different parts of the same tree canopy.

- Can lead to adaptive radiation when species diversify into many specialised niches.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how pollinator diversity affects floral morphology and resource partitioning in wild plant communities.