B3.2.1 – TRANSPORT IN PLANTS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Xylem | Vascular tissue transporting water and minerals from roots to leaves, composed of dead lignified cells. |

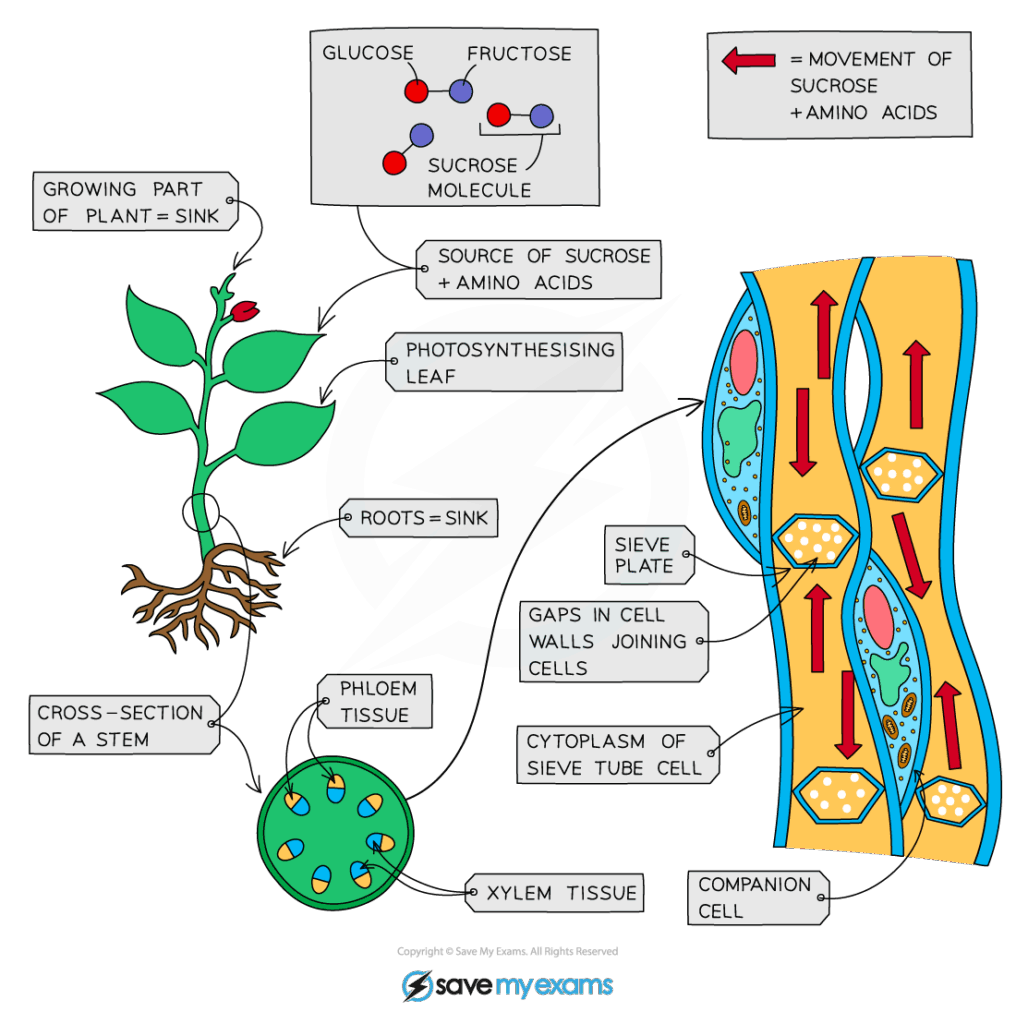

| Phloem | Vascular tissue transporting sugars and other organic compounds from sources to sinks, composed of living sieve tube elements and companion cells. |

| Transpiration | Loss of water vapour from plant leaves, primarily through stomata. |

| Cohesion-Tension Theory | Explains water movement in xylem due to cohesion between water molecules and tension from transpiration. |

| Translocation | Movement of sugars and other organic compounds in phloem from sources (e.g., leaves) to sinks (e.g., roots, fruits). |

| Source | Plant organ where sugars are produced or released into phloem. |

| Sink | Plant organ where sugars are consumed or stored. |

📌Introduction

Plants transport water, minerals, and organic compounds through two specialised vascular tissues — xylem and phloem. The movement of substances relies on physical forces such as cohesion, adhesion, and pressure gradients, rather than direct pumping by a heart-like organ. These systems are essential for photosynthesis, nutrient distribution, growth, and survival in varying environments.

❤️ CAS Link: Lead a school garden irrigation project that measures water usage and links plant growth rates to transpiration efficiency.

📌 Water Transport in Xylem

- Structure — Xylem vessels are hollow, lignified tubes with no cytoplasm, providing an uninterrupted pathway for water.

- Cohesion — Hydrogen bonding between water molecules ensures continuous columns of water.

- Adhesion — Attraction between water molecules and xylem walls helps counter gravity.

- Tension — Created by transpiration at leaf surfaces, pulling water upwards.

- Root Pressure — Osmotic influx of water into roots can push water upwards, especially at night.

🧠 Examiner Tip: In cohesion-tension explanations, always mention negative pressure and continuous water columns to get full marks.

📌 Phloem Structure and Translocation

- Sieve Tube Elements — Living cells with perforated sieve plates for flow between cells.

- Companion Cells — Contain mitochondria for active transport of sucrose into sieve tubes.

- Source-to-Sink Flow — Driven by pressure-flow mechanism; loading of sucrose at sources increases osmotic pressure, driving water in and pushing sap towards sinks.

- Bidirectional Flow — Phloem can transport substances in both directions depending on source-sink locations.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Phloem-feeding pests like aphids are used by scientists to study phloem sap composition via stylet sampling.

📌Transpiration

- Occurs mainly through stomata during gas exchange.

- Rate influenced by light intensity, temperature, humidity, wind speed.

- Guard cells regulate stomatal opening to balance CO₂ uptake with water loss.

- Xerophytic Adaptations — Thick cuticle, sunken stomata, hairy leaves reduce water loss.

🔍 TOK Perspective: The way we measure transpiration (potometer readings, gas exchange) can influence our understanding of plant water use and may not always reflect real-world field conditions.

📌Adaptations for Transport

- Hydrophytes — Large air spaces for buoyancy and gas diffusion; reduced xylem.

- Halophytes — Salt-secreting glands, succulent leaves to store water.

- Tall Trees — Wide vessel diameters, reinforced walls to withstand negative pressures.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate the relationship between leaf surface adaptations and transpiration rates in plants from contrasting environments.

📌 Transport and Climate Interactions

- Climate change affects transpiration rates, altering plant water balance.

- Higher CO₂ can reduce stomatal density, influencing transpiration efficiency.