Probability provides a structured way to quantify uncertainty. In IB Mathematics, probability concepts help students

reason about chance events, evaluate risks, and analyse patterns in real-world scenarios such as genetics, finance,

gambling, and scientific experiments. This topic covers foundational ideas of trials, outcomes, equally likely events,

relative frequency, sample spaces, complementary events, and the expected number of occurrences.

1. Trials, Outcomes & Sample Spaces

Concepts of trial and outcome

- Trial: A single performance of an experiment (e.g., rolling a die once).

- Outcome: The result obtained from a trial (e.g., rolling a 4).

- Outcome set: All individual possible results the experiment can generate.

- Outcomes are typically considered atomic — meaning they cannot be broken down further.

Equally likely outcomes

- Outcomes are equally likely when each outcome has the same probability of occurring.

- This assumption is vital for theoretical probability, e.g., a fair die where each face has probability 1/6.

- In real life, “equally likely” rarely holds perfectly—this is why experimentation and simulation are used.

Sample space U

- The sample space (U) is the complete set of all possible outcomes of an experiment.

- It can be represented as a list, table, tree diagram, or even a grid for two-variable situations.

- Choosing a clear representation reduces errors in probability calculations.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Actuarial science constructs sample spaces for life expectancy predictions

and uses probability to set insurance premiums. This involves extremely large and structured sample spaces

based on population data, age brackets, lifestyle categories, and health factors.

2. Events, Relative Frequency & Theoretical Probability

Event and its probability

- An event is a collection of outcomes (e.g., rolling an even number = {2,4,6}).

- The probability of event A is given by:

P(A) = n(A) / n(U)

where n(A) = number of favorable outcomes, and n(U) = total number of outcomes. - This applies only when outcomes are equally likely.

Relative frequency

- Relative frequency approximates probability using repeated experimentation.

- Formula: relative frequency = (number of successful trials) / (total trials).

- The more trials performed, the closer the relative frequency tends to the true probability.

- This aligns with the Law of Large Numbers.

🔍 TOK Perspective: How do repeated experiments influence our confidence in probability?

Does probability measure truth, or simply our uncertainty?

In medicine and economics, “probability” often represents beliefs, not physical frequencies.

3. Complementary Events

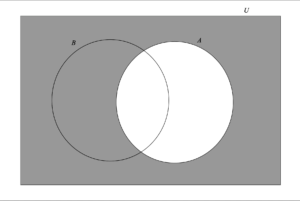

Understanding A and A’

- The complement A’ contains all outcomes in the sample space that are not in A.

- The probabilities satisfy: P(A) + P(A’) = 1.

- Complementary reasoning is one of the fastest methods for calculating probabilities.

- Often used when finding “at least one success” in repeated trials.

- In the below image, the area shaded in grey is the A’ or A complement

Example: If the probability of rain today is 0.3, then the probability it does not rain is 1 – 0.3 = 0.7.

4. Expected Number of Occurrences

Meaning of expectation

- The expected number is the long-run average count of occurrences of an event.

- Formula: Expected value = n × P(A), where n = number of trials.

- Expectation does not mean the event will occur that exact number of times.

- It is a theoretical average over very large numbers of repetitions.

Example: If a class has 128 students and the probability a student is absent is 0.1,

Expected absentees = 128 × 0.1 = 12.8 students.

🟢 GDC Tip: Use probability simulation functions on your calculator to approximate long-run expected values.

With enough trials, the simulated average stabilises close to the expected value.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Expected value is the foundation of insurance risk modeling,

gambling strategy analysis, actuarial forecasting, and Monte Carlo simulations used in

engineering and finance. It is directly tied to how risks are priced and how companies predict losses.

🔍 TOK Perspective: The St. Petersburg paradox shows how expected value can fail to match human intuition.

Why does a game with infinite expected value appear “not worth much”?

This raises philosophical questions about value, risk, and rationality.