In three–dimensional space, lines can relate to each other in several different ways.

They may lie on top of one another, never meet, cross at a single point, or miss each other completely while not being parallel.

This topic explains how to distinguish coincident, parallel, intersecting and skew lines and how to find points of intersection using vector or parametric equations.

📌 1. Types of Line Relationships in 3D

Suppose we have two lines written in vector form:

Line 1: r = a + λb

Line 2: r = c + μd

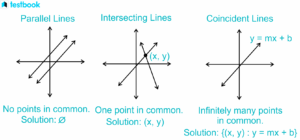

- Coincident lines

These are actually the same line.

Direction vectors are parallel (b is a scalar multiple of d) and at least one point on Line 1 also lies on Line 2.

There are infinitely many points of intersection. - Parallel lines

Lines that have the same direction but are not the same line.

Direction vectors are scalar multiples, but no point from one line satisfies the equation of the other.

They never meet. - Intersecting lines

Lines cross at a single common point.

Direction vectors are not scalar multiples, and there exist values λ and μ that make

a + λb = c + μd.

That common vector gives the intersection point. - Skew lines

Lines that are not parallel and do not intersect.

This can only happen in three dimensions because the lines lie in different planes.

When you try to solve a + λb = c + μd there is no solution.

📌 2. Finding Points of Intersection

For two lines in vector form:

Line 1: r = a + λb = (a1, a2, a3) + λ(b1, b2, b3)

Line 2: r = c + μd = (c1, c2, c3) + μ(d1, d2, d3)

Equate components:

a1 + λb1 = c1 + μd1

a2 + λb2 = c2 + μd2

a3 + λb3 = c3 + μd3

Solve for λ and μ:

- Exactly one solution → the lines intersect at that point.

- No solution → the lines are skew (if not parallel).

- Infinitely many solutions → the lines are coincident.

📌 3. Mini Worked Example

Example: Classify the relationship between the lines.

Line 1: r = (1, 0, 2) + λ(2, 1, −1)

Line 2: r = (3, 1, 4) + μ(−1, 0, 2)

Step 1 — Check if direction vectors are multiples.

b = (2, 1, −1), d = (−1, 0, 2).

There is no single constant k such that d = k × b, so the lines are not parallel.

Step 2 — Try to find intersection.

Equate components:

1 + 2λ = 3 − μ (1)

0 + λ = 1 (2)

2 − λ = 4 + 2μ (3)

From (2): λ = 1.

Substitute into (1): 1 + 2 × 1 = 3 − μ → 3 = 3 − μ → μ = 0.

Check in (3): 2 − 1 = 4 + 2 × 0 → 1 = 4 ❌ (false).

There is no pair (λ, μ) that satisfies all three equations, therefore the lines are

skew (non–parallel and non–intersecting).

🌍 Real-World Connection

- In architecture and engineering, skew beams and supports must be identified so that loads and stresses are calculated correctly.

- In air traffic control, flight paths are modelled as lines in 3D; understanding when paths intersect or stay skew is essential for safety.

- In computer graphics and ray tracing, lines representing rays of light are checked for intersections with objects in 3D scenes.

📊 IA Spotlight

- Investigate the shortest distance between two skew lines using vector projection and optimisation. This gives good mathematical depth and clear real–world links.

- Model the motion of two objects moving along different lines in space and explore conditions for collision or near miss.

- Use technology to visualise how changing direction vectors or starting points changes the relationship between lines.

🌐 EE Focus

- Explore vector geometry of lines and planes in higher dimensions, including skew lines and distances between them.

- Study the mathematics behind navigation systems or 3D positioning, where paths and bearings are represented as lines in space.

❤️ CAS Link

- Create a hands–on workshop for younger students using sticks or 3D printed rods to demonstrate coincident, parallel, intersecting and skew lines.

- Work with the physics department to help students model experiments using 3D line diagrams and intersection checks.

🔍 TOK Perspective

- In two dimensions, two non–parallel lines must intersect, but in three dimensions they may be skew. What does this tell us about the role of dimension in shaping mathematical truth?

- Our visual intuition often fails for skew lines. To what extent do algebraic and symbolic methods extend our ability to “see” beyond perception?

🧠 Examiner Tip

Always test whether direction vectors are scalar multiples before attempting any simultaneous equations.

If they are multiples, you know immediately that the lines are either parallel or coincident,

and you only need to check one point to decide which.