This part of the course focuses on using trigonometry and Pythagoras’ theorem in real situations.

You will turn written descriptions into clear labelled diagrams, identify right or non-right triangles, and then choose the correct method: Pythagoras, basic trig ratios, sine rule or cosine rule.

Contexts include heights and distances, navigation, bearings, triangulation and map-making.

| Idea | Description |

|---|---|

| Pythagoras’ theorem | In a right-angled triangle: hypotenuse2 = opposite2 + adjacent2. Used to link distances when one angle is 90°. |

| Right-angled trig | sin, cos and tan connect angles with side ratios. Used for angles of elevation and depression and many height or depth problems. |

| Non-right-angled trig | Sine rule and cosine rule solve triangles that are not right-angled, especially in navigation and triangulation. |

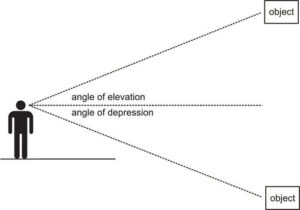

| Angles of elevation and depression | Angles measured from a horizontal line of sight up or down. They always start at the eye level of the observer. |

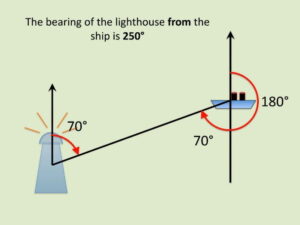

| Bearings | Three-digit angles measured clockwise from North, used to describe directions in navigation and map-based questions. |

📌 1. Applications of right and non-right angled trigonometry

Trigonometry becomes powerful when you recognise a triangle hidden inside a real situation.

The general approach is:

- Translate the word problem into one or more triangles.

- Decide whether each triangle is right-angled or non-right-angled.

- Select the appropriate method:

- Pythagoras or basic sin, cos, tan for right-angled cases.

- Sine rule or cosine rule for non-right-angled cases (using the patterns from SL 3.2).

- Use the units and context (height, distance, speed) to interpret your answer.

In map-making and triangulation, several triangles are formed by joining observation points to a target.

Distances that are hard to measure directly (for example across a river or to a tall tower) can be found by measuring more accessible lengths and angles and then applying trigonometry.

Illustrative scenario — combining Pythagoras and trig

A surveyor stands 40 metres from the base of a building on flat ground.

The angle of elevation to the top is 32°. The roof has a short vertical antenna whose top is 5 metres higher than the roof itself.

Step one is to model the building without the antenna using a right-angled triangle: ground, building height, and line of sight.

Using tan 32° = height ÷ 40, the height of the building alone is 40 × tan 32°.

The total height including the antenna is then that value plus 5 metres.

The exact calculator evaluation is less important here than the reasoning:

the triangle lets us express an unreachable vertical distance in terms of a measurable horizontal distance and a measurable angle.

📌 2. Angles of elevation and depression

These angles appear in almost every “height or depth” question and are a frequent source of mistakes, so definitions must be very clear:

- Angle of elevation

The angle measured upwards from a horizontal line of sight to an object that is higher than the observer.

Example: looking up at a plane or the top of a tower. - Angle of depression

The angle measured downwards from a horizontal line of sight to an object that is lower than the observer.

Example: looking down from a cliff to a boat on the sea. - The angle of elevation from point A to point B is equal to the angle of depression from B to A, because alternate interior angles are equal when you draw the horizontal lines.

- The horizontal line of sight is always at eye level, not on the ground. Forgetting this shifts the triangle and often changes which side is opposite or adjacent.

Once the triangle is drawn, usually one side is given as a horizontal distance (ground distance or distance at sea level) and the vertical side represents the height to be found.

You choose tan, sin or cos depending on which lengths are known or required.

https://www.ck12.org/book/cbse-maths-book-class-x/section/9.2/

📌 3. Bearings, navigation and non-right triangles

Many application questions combine distances, bearings and trigonometry. Bearings give direction in navigation:

- Bearings are measured as three-digit angles from North, turning clockwise.

For example, a ship travelling on a bearing of 060° is heading 60° east of North. - The bearing from A to B is not generally the same as the bearing from B to A. The return bearing is usually 180° different, adjusted to stay within 000° to 359°.

- To use trig, you normally convert the bearing into an interior angle in a triangle by marking North at each point and drawing the directions as rays.

- Often two journeys form two sides of a triangle and the angle between them is known from the difference in bearings. This can create a non-right-angled triangle where the cosine rule or sine rule is needed.

Navigation questions sometimes ask for the displacement between start and finish or for the bearing from one point to another. In both cases you:

- Draw a scaled diagram with North lines at main points.

- Mark distances along the bearings.

- Identify the triangle formed by the journeys and apply trigonometry to find the third side or missing angle.

📌 4. Constructing labelled diagrams from written statements

Drawing a correct diagram is often half the marks in an applications question. A systematic approach helps:

- Step 1: Identify objects. Who or what is at each point? For example, observer, tower, boat, ship A, ship B, radio mast.

- Step 2: Decide on a view. Side view (for heights and angles of elevation or depression) or plan view from above (for bearings and maps).

- Step 3: Mark known distances and angles. Use clear labels like 40 m, 2.5 km, 60°. If using bearings, draw a North arrow at each relevant point first.

- Step 4: Mark right angles clearly. Use a small square symbol to indicate a 90° corner at the base of a building or where horizontal meets vertical.

- Step 5: Decide the triangle type. Right-angled or non-right-angled, then choose Pythagoras, basic trig or sine / cosine rule accordingly (with the ÷ and × notation in your algebra).

- Step 6: Write a short sentence conclusion. For example, “The height of the building is approximately 23.4 m” or “The ship must travel 18.2 km on a bearing of 132°.”

🧮 GDC Use

- Use the calculator’s trig functions to evaluate expressions like 40 × tan 32° or to compute inverse trigonometric functions quickly.

- When solving multi-step problems, store intermediate values in memory (for example, the height found from one triangle that is used in a second triangle) to avoid rounding errors.

- Some GDCs can draw simple triangles or show values in a table, which can be used to check whether your answers for heights or distances are reasonable.

- Always show the algebraic setup in your written work; the GDC is for numerical evaluation, not for replacing reasoning.

🌍 Real-World Connections

- Triangulation and surveying: Used to map coastlines, mountain ranges and city layouts by measuring angles from known baseline distances.

- Navigation and aviation: Pilots and ship captains use bearings and angles of elevation or depression when approaching runways or navigating around hazards.

- Radio and satellite communication: Positioning of radio towers and satellite dishes relies on angles and heights to maximise signal strength.

- Parallax methods in astronomy: Distances to nearby stars can be estimated using tiny angles and Earth’s orbital radius as the baseline.

📐 IA Spotlight

- Investigate the accuracy of height measurements found using angles of elevation from different distances away from a building or tree.

- Design a small triangulation project in your local area, using multiple observation points and bearings to estimate the position of an inaccessible point.

- Compare measurements obtained using trigonometry with those from digital tools such as phone range-finder apps or mapping software, and analyse discrepancies.

🌐 EE Focus

- Explore the historical development of triangulation and its role in determining the size and curvature of the Earth, including early geodetic surveys.

- Examine different proofs and generalisations of Pythagoras’ theorem, including those that apply in non-Euclidean geometries where the angle sum of a triangle is not 180°.

- Investigate how modern GPS systems conceptually rely on distance and angle ideas, and compare this with classical triangulation methods.

🔍 TOK Perspective

- In Euclidean geometry the angles of a triangle add to 180°, but on curved surfaces this is no longer true. What does this say about the status of mathematical truths?

- When explorers used trigonometry to estimate Earth’s size, how did they decide whether the models and measurements were “good enough” to count as knowledge?

- Many cultures contributed to trigonometry and proofs of Pythagoras’ theorem. How does recognising this global history affect our view of ownership and authorship in mathematics?

❤️ CAS Ideas

- Organise a “geometry walk” around your school, where participants estimate heights or widths of buildings and trees using simple trigonometric tools.

- Create an interactive workshop for younger students on bearings and map-reading, using small navigation challenges in the playground or local park.

- Collaborate with geography or physics teachers to design a field study that measures slopes, distances and directions in a nearby natural area.

📝 Paper 1 and Paper 2 Tips

- Start every problem with a neat, labelled diagram. Most mistakes in this topic come from missing or mis-labelled angles and distances.

- Clearly state which method you are using: “Using Pythagoras”, “Using sin rule”, “Using cosine rule”, or “Using right-angled trig and tan”.

- Keep angle mode in degrees unless the question explicitly uses radians, and check that answers are reasonable (for example, a height should not be less than a horizontal distance if the angle of elevation is large).

- Round only at the end of your solution, especially if one result is reused in a later calculation.

🧠 Examiner Tip

Examiners report that many students try to jump straight to formulas without first understanding the situation.

Marks are often lost because of an incorrect diagram or misidentified angle.

If you take time to sketch, label and think about the story the question is telling, the trigonometry becomes routine and you gain both method and accuracy marks.