A2.3.1 – VIRUS STRUCTURE

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Virus | An infectious particle made of nucleic acid enclosed in a protein coat, sometimes with an envelope. |

| Capsid | Protein shell that encloses the viral genome. |

| Envelope | Membrane derived from the host cell, containing viral proteins and glycoproteins. |

| Bacteriophage | Virus that infects bacteria. |

| Retrovirus | Virus with RNA genome that uses reverse transcriptase to integrate into host DNA. |

| Host Range | The spectrum of host species or cells a virus can infect. |

📌Introduction

Viruses are non-cellular infectious agents that rely entirely on a host cell to reproduce. They have no metabolism or organelles and cannot carry out life processes independently. Structurally, viruses are made up of nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) surrounded by a capsid, and in some cases, an additional lipid envelope.

❤️ CAS Link: Develop an educational infographic explaining how viruses differ from living cells, for use in a school health awareness campaign.

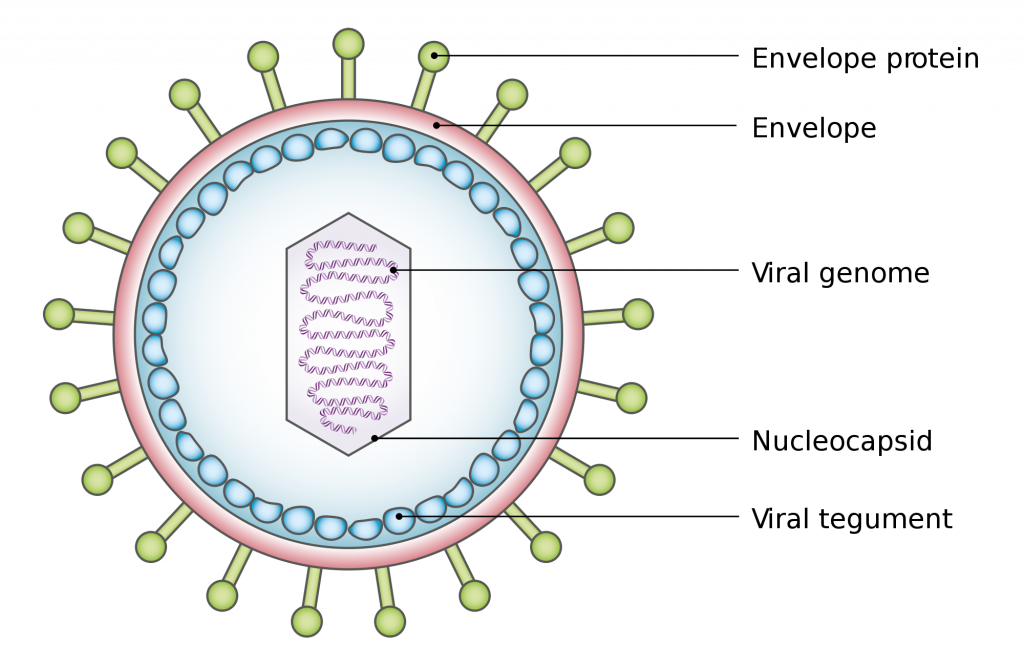

📌 Basic Structure of Viruses

- All viruses contain genetic material — either DNA or RNA, but never both.

- The genome can be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), and linear or circular.

- A capsid made of protein subunits (capsomeres) encloses and protects the genome.

- Some viruses have an envelope derived from the host cell membrane, containing viral glycoproteins.

- Enveloped viruses are generally more sensitive to heat, detergents, and desiccation.

- Non-enveloped viruses rely on their stable capsid for protection and tend to be more resistant to environmental changes.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always state whether a virus is enveloped or non-enveloped when describing its structure — this is often linked to exam questions about viral survival outside a host.

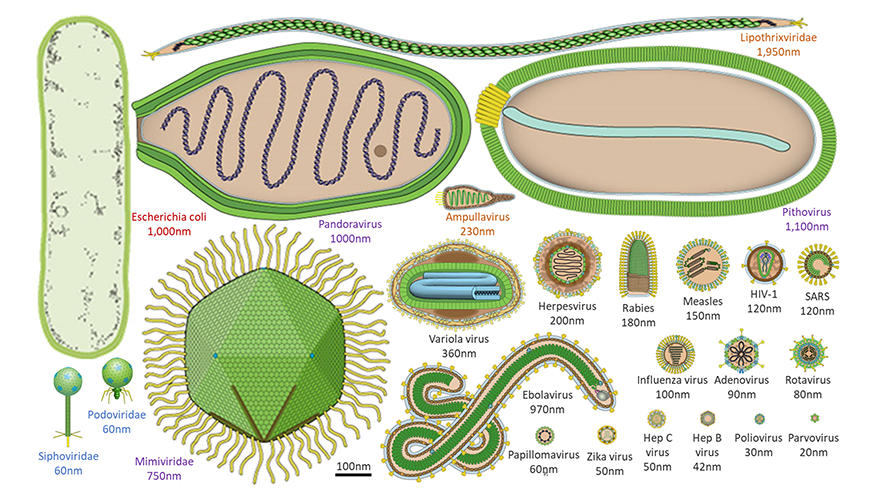

📌 Structural Diversity in Viruses

- Helical viruses: Capsid proteins arranged in a spiral (e.g., tobacco mosaic virus).

- Icosahedral viruses: Symmetrical 20-sided capsid (e.g., adenoviruses).

- Complex viruses: More elaborate structures (e.g., bacteriophages with head-tail arrangement).

- Enveloped viruses: Have a lipid layer containing viral glycoproteins (e.g., influenza virus, HIV).

- Non-enveloped viruses: Lack lipid envelope (e.g., poliovirus).

- Capsid shape is determined by the arrangement of capsomeres and can influence host interactions.

🌍 Real-World Connection: The structural stability of non-enveloped viruses makes them persistent on surfaces, explaining why norovirus outbreaks spread rapidly in schools and cruise ships.

📌 Genetic Material in Viruses

- Viral genomes can be DNA or RNA, single-stranded or double-stranded.

- RNA viruses tend to have higher mutation rates due to lack of proofreading by RNA polymerases.

- DNA viruses generally have more stable genomes.

- Retroviruses use reverse transcriptase to make DNA from their RNA genome, integrating into host DNA.

- Segmented genomes (e.g., influenza virus) can undergo reassortment, leading to new strains.

- Genome type affects replication strategies and host immune responses.

🔍 TOK Perspective: How do classification systems for viruses challenge our definition of “living” versus “non-living” things?

📌 Special Adaptations for Host Infection

- Viral surface proteins (ligands) bind to specific host cell receptors, determining host range.

- Bacteriophages have tail fibres for attachment to bacterial surfaces.

- Enveloped viruses enter cells via membrane fusion or endocytosis.

- Non-enveloped viruses often inject genetic material directly into the host cytoplasm.

- Some viruses encode proteins that suppress host immune responses.

- Structural adaptations allow evasion of immune detection and efficient cell entry.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how changes in viral surface glycoproteins affect infection efficiency in different host cell types.