1.2 SYSTEMS

📌 Definitions Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| System | A set of interrelated parts that work together to form a functioning whole, with inputs, outputs, storages, and flows of energy or matter. |

| Transfers | Movements of energy or matter through a system without changing its form or state (e.g., water flow, animal migration). |

| Transformations | Processes that change energy or matter from one form or state to another (e.g., photosynthesis, respiration). |

| Emergent Properties | Characteristics that arise from the interactions of system components, not present in the individual parts alone. |

| Trophic Cascades | Indirect effects in an ecosystem triggered when changes in predator populations alter the abundance or behavior of prey and lower trophic levels. |

| Predator–Prey Cascades | A type of trophic cascade where predators regulate prey populations, maintaining ecosystem balance and biodiversity. |

| Global Geochemical Cycles | Large-scale natural processes that circulate elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus through the Earth’s spheres. |

| Dynamic Equilibrium | A state of balance within a system where inputs and outputs fluctuate around a stable average over time. |

| Terrariums | Closed, self-sustaining micro-ecosystems used to model energy and matter flow in a controlled environment. |

| Microcosm | A small-scale, simplified model of an ecosystem used to study ecological processes under controlled conditions. |

| Homeostasis | The tendency of a system to maintain internal stability despite external changes through feedback mechanisms. |

| Anthropomorphism | The attribution of human traits or emotions to non-human entities, often leading to biased interpretations in ecology. |

| Albedo | The fraction of solar radiation reflected by a surface; high albedo surfaces (like ice) reflect more sunlight, affecting climate regulation. |

| Reproductive Potential | The maximum possible rate of reproduction of a species under ideal environmental conditions. |

| Tipping Points | Critical thresholds where small changes lead to drastic, often irreversible, shifts in system state or stability. |

| Resilience | The capacity of a system to resist or recover from disturbance while maintaining its structure and function. |

| Model | A simplified representation of a system used to describe, explain, or predict environmental phenomena. |

🧠 Exam Tip: It is important to keep definitions concise but include keywords like system, equilibrium, feedback, transformation, energy flow to show conceptual understanding.

📌 The Systems Approach

- A systems approach is a way of visualizing a complex set of interactions which may be ecological or societal.

🔍 TOK Tip: To what extent can ecological models predict real-world outcomes?

- A systems approach is the term used to describe a method of simplifying and understanding a complicated set of interactions

- Systems, and the interactions they contain, may be environmental or ecological (e.g. the water cycle or predator-prey relationships), social (e.g. how we live and work) or economic (e.g. financial transactions or business deals)

- The interactions within a system, when looked at as a whole, produce the emergent properties of the system

- For example, in an ecosystem, all the different ecological interactions occurring within it shape how that ecosystem looks and behaves – if the interactions change for some reason (e.g. a new predator is introduced), then the emergent properties of the ecosystem will change too

- There are two main ways of studying systems:

- A reductionist approach involves dividing a system into its constituent parts and studying each of these separately – this can be used to study specific interactions in great detail but doesn’t give the overall picture of what is occurring within the system as a whole

- A holistic approach involves looking at all processes and interactions occurring within the system together, in order to study the system as a whole

- For example, sustainability or sustainable development depends on a highly complex set of interactions between many different factors

- These include environmental, social and economic factors (sometimes referred to as the three pillars of sustainability

- A systems approach is required in order to understand how these different factors combine and interact with one another, as well as how they all work together as a whole (the holistic approach)

- These interactions produce the emergent properties of the system.

- The concept of a system can be applied to a range of scales.

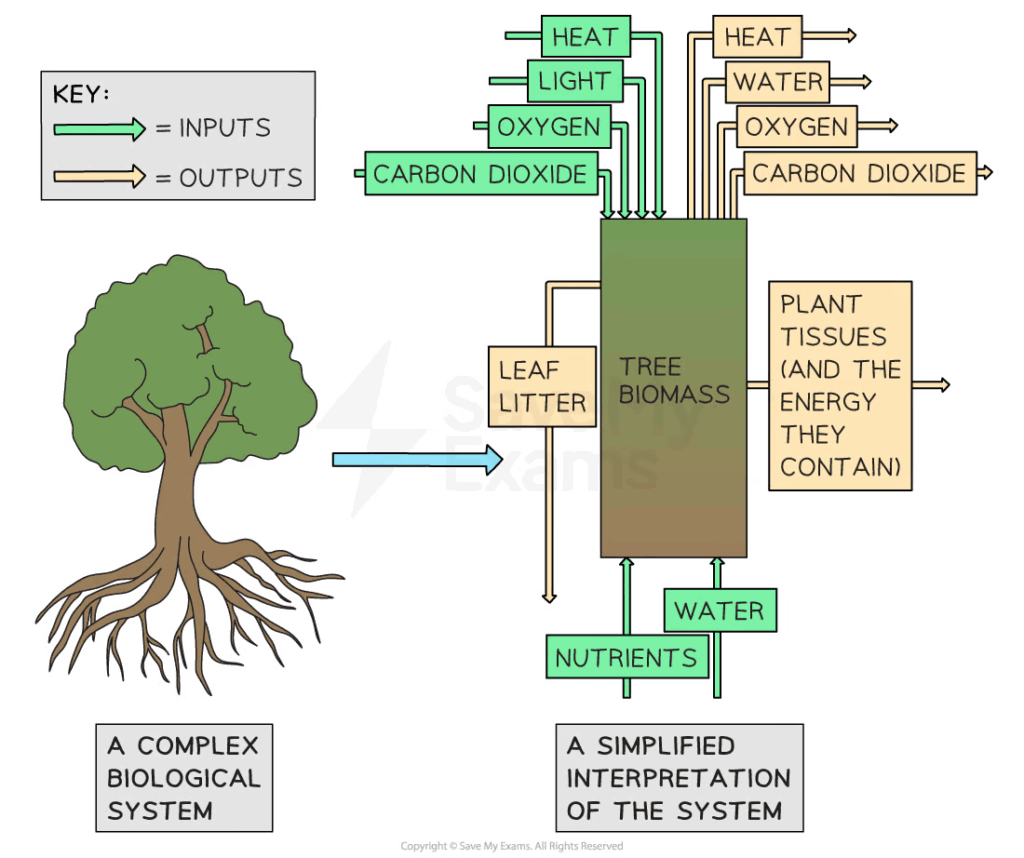

- A system consists of storages and flows.

- The flows provide inputs and outputs of energy

- The flows are processes and may be either transfers (a change in location) or transformations (a change in the chemical nature, a change in state or a change in energy).

- The flows are processes that may be either:

- Transfers (a change in location)

- Transformations (a change in the chemical nature, a change in state or a change in energy)

Transfers and Transformations

- These are two fundamental concepts in systems (and systems diagrams) that help to understand how matter and energy move through a system

- Transfers are the movement of matter or energy from one component of the system to another, without any change in form or quality

- For example, water flowing from a river to a lake is a transfer

- Transformations, on the other hand, involve a change in the form or quality of matter or energy as it moves through the system

- For example, when sunlight is absorbed by plants, it is transformed into chemical energy through the process of photosynthesis

- Transfers and transformations are often represented in systems diagrams by arrows that connect the different components of the system

- Arrows that represent transfers are usually labeled with the quantity of matter or energy being transferred (e.g., kg of carbon, kJ of energy), while arrows that represent transformations may include additional information about the process involved (e.g., photosynthesis, respiration)

- Systems diagrams can help to identify the key transfers and transformations that occur within a system and how they are interconnected

- By understanding these processes, it is possible to identify opportunities to improve the efficiency or sustainability of the system

- Transfers and transformations can occur at different scales within a system, from the molecular level to the global level

- For example, at the molecular level, nutrients are transferred between individual organisms, while at the global level, energy is transferred between different biomes

Image source: savemyexams.com

🌐 EE Tip: Choose a local issue (e.g. landfill management or wetland conversion) and apply systems diagrams to analyze inputs, outputs, and feedback loops.

📌 Types of Systems

- There are three main types of systems. These are:

- Open systems

- Closed systems

- Isolated systems

- The category that a system falls into depends on how energy and matter flow between the system and the surrounding environment

Open Systems

- Both energy and matter are exchanged between the system and its surroundings

- Open systems are usually organic (living) systems that interact with their surroundings (the environment) by taking in energy and new matter (often in the form of biomass), and by also expelling energy and matter (e.g. through waste products or by organisms leaving a system)

- An example of an open system would be a particular ecosystem or habitat

- Your body is also an example of an open system – energy and matter are exchanged between you and your environment in the form of food, water, movement and waste

Closed Systems

- Energy, but not matter, is exchanged between the system and its surroundings

- Closed systems are usually inorganic (non-living), although this is not always the case

- The International Space Station (ISS) could perhaps be seen as a closed system

- It is a self-contained environment that must maintain a balance of resources, including air, water, and food, as well as waste management, energy production, and temperature control

- The ISS cannot exchange matter with its surroundings

- The Earth (and the atmosphere surrounding it) could be viewed as a closed system

- The main input of energy occurs via solar radiation

- The main output of energy occurs via heat (re-radiation of infrared waves from the Earth’s surface)

- Matter is recycled completely within the system

- Although, technically, very small amounts of matter enter and leave the system (in the form of meteorites or spaceships and satellites), these are considered negligible

- Artificial and experimental ecological closed systems can also exist – for example, sealed terrariums, containing just the right balance of water and living organisms (such as mosses, ferns, bacteria, fungi or invertebrates) can sometime survive for many years as totally closed systems, if light and heat energy is allowed to be exchanged across the glass boundary

Isolated Systems

- Neither energy nor matter is exchanged between the system and its surroundings

- Isolated systems do not exist naturally – they are more of a theoretical concept (although the entire Universe could be considered to be an isolated system)

- Ecosystems are open systems. Closed systems only exist experimentally although the global geochemical cycles approximate to closed systems.

Systems at different scales

- Systems are structures made up of interconnected parts that work together towards a common goal or function

- In a similar way, environmental systems are interconnected networks of components and processes within the environment, found at various scales from single organisms to huge ecosystems

- These environmental systems include interactions between living organisms, their habitats and physical elements like water, air and soil, shaping Earth’s environment and influencing its dynamics and functions

- Environmental systems can be observed and analysed at a range of different scales

- For example, a bromeliad (a type of plant commonly found in tropical rainforests) could represent a small-scale local ecological system

- Within the leaves of the bromeliad, various organisms interact, forming a microcosm of life

- The entire rainforest itself represents a large-scale ecosystem, where countless species interact within a complex web of relationships

- Within the rainforest, there are predator-prey relationships, symbiotic relationships, species competing for resources and nutrient cycles all occurring within the system

- It could also be argued that the entire planet can be considered to be one giant, self-contained system

- The Earth’s atmosphere, oceans and land are highly interconnected and regulate environmental conditions to maintain conditions suitable for life

- For example, a bromeliad (a type of plant commonly found in tropical rainforests) could represent a small-scale local ecological system

Earth as a single integrated system

- Instead of just a collection of independent parts, Earth can be seen as a complex, integrated system comprised of many interconnected components, including:

- Biosphere: includes all living organisms on Earth and their interactions with the environment

- Hydrosphere: includes all water bodies on Earth, including oceans, rivers, lakes and groundwater

- Cryosphere: includes all forms of frozen water on Earth’s surface, such as glaciers, ice caps and permafrost

- Geosphere: refers to the solid Earth, including rocks, minerals and landforms such as mountains and valleys

- Atmosphere: includes the layer of gases surrounding the Earth, including the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere and exosphere

- Anthroposphere: represents the sphere of human influence on the environment, including human activities, infrastructure and urbanisation

Gaia hypothesis

- The Gaia hypothesis (also known as the Gaia theory), initially proposed by James Lovelock in the 1970s, presents a holistic view of the Earth as a single, self-regulating system

- Lovelock proposed that Earth’s biota (living organisms) and their environment are closely linked and act together as an integrated system

- His theory suggests that feedback mechanisms within Earth’s systems help maintain stability and balance on a global scale, a bit like homeostasis in living organisms

- Variations and developments:

- Initially, the Gaia hypothesis was introduced to explain how the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere affects global temperatures and how these two factors are connected or “controlled” via complex feedback methods

- For example, the presence of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, in the Earth’s atmosphere can increase global temperatures

- In response to these rising temperatures, feedback mechanisms, such as increased evaporation leading to more cloud cover or enhanced plant growth absorbing more carbon dioxide, may act to mitigate temperature increases

- Over time, the Gaia hypothesis has undergone various interpretations and refinements, with contributions from scientists such as Lynn Margulis

- Some scientists have criticised the Gaia hypothesis for its anthropomorphism, comparing the Earth to a living organism, and lack of testability, while others consider it a useful theory for understanding Earth’s interconnected systems

- Initially, the Gaia hypothesis was introduced to explain how the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere affects global temperatures and how these two factors are connected or “controlled” via complex feedback methods

📌 Stable Equilibrium and Feedback Mechanisms

Equilibria

- An equilibrium refers to a state of balance occurring between the separate components of a system

- Open systems (such as ecosystems) usually exist in a stable equilibrium

- This means they generally stay in the same state over time

- They can be said to be in a state of balance

- A stable equilibrium allows a system to return to its original state following a disturbance

Stable Equilibria

- The main type of stable equilibrium is known as steady-state equilibrium

- A steady-state equilibrium occurs when the system shows no major changes over a longer time period, even though there are often small, oscillating changes occurring within the system over shorter time periods

- These slight fluctuations usually occur within closely defined limits and the system always return back towards its average state

- Most open systems in nature are in steady-state equilibrium

- For example, a forest has constant inputs and outputs of energy and matter, which change over time

- As a result, there are short-term changes in the population dynamics of communities of organisms living within the forest, with different species increasing and decreasing in abundance

- Overall however, the forest remains stable in the long-term

- Another type of stable equilibrium would be static equilibrium

- There are no inputs or outputs (of energy or matter) to the system and therefore the system shows no change over time

- No natural systems are in static equilibrium – all natural systems (e.g. ecosystems) have inputs and outputs of energy and matter

- Inanimate objects such as a chair or desk could be said to be in static equilibrium

Static and steady-state equilibria are both types of stable equilibria

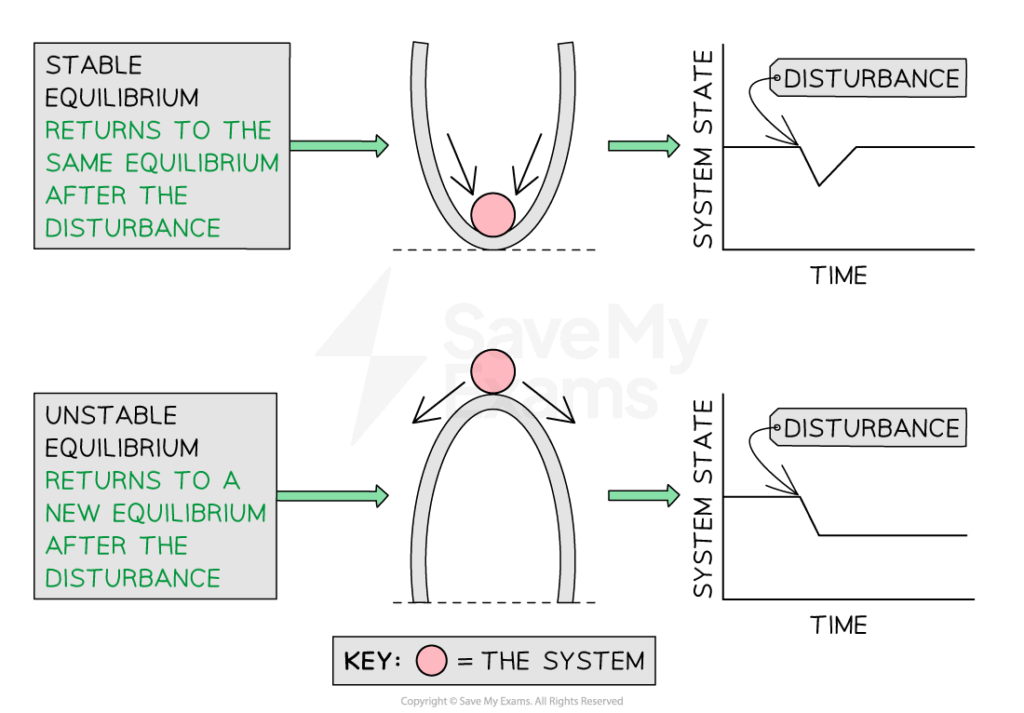

Stable vs Unstable Equilibria

- A system can also be in an unstable equilibrium

- Even a small disturbance to a system in unstable equilibrium can cause the system to suddenly shift to a new system state or average state (i.e. a new equilibrium is reached)

Image source: savemyexams.com

A system can be in a stable equilibrium or an unstable equilibrium

Positive & Negative Feedback

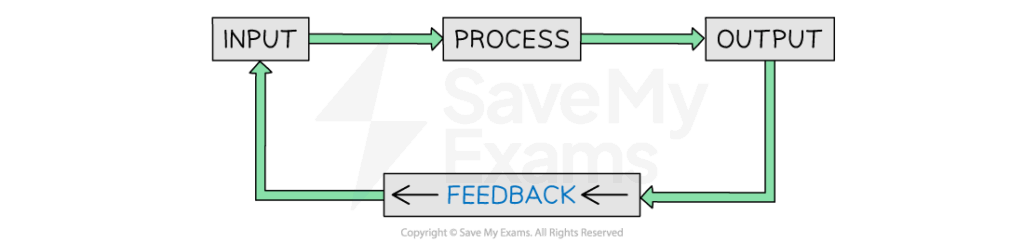

- Most systems involve feedback loops

- These feedback mechanisms are what cause systems to react in response to disturbances

- Feedback loops allow systems to self-regulate

Image source: savemyexams.com

Changes to the processes in a system (disturbances) lead to changes in the system’s outputs, which in turn affect the inputs

- There are two types of feedback loop:

- Negative feedback

- Positive feedback

Negative Feedback

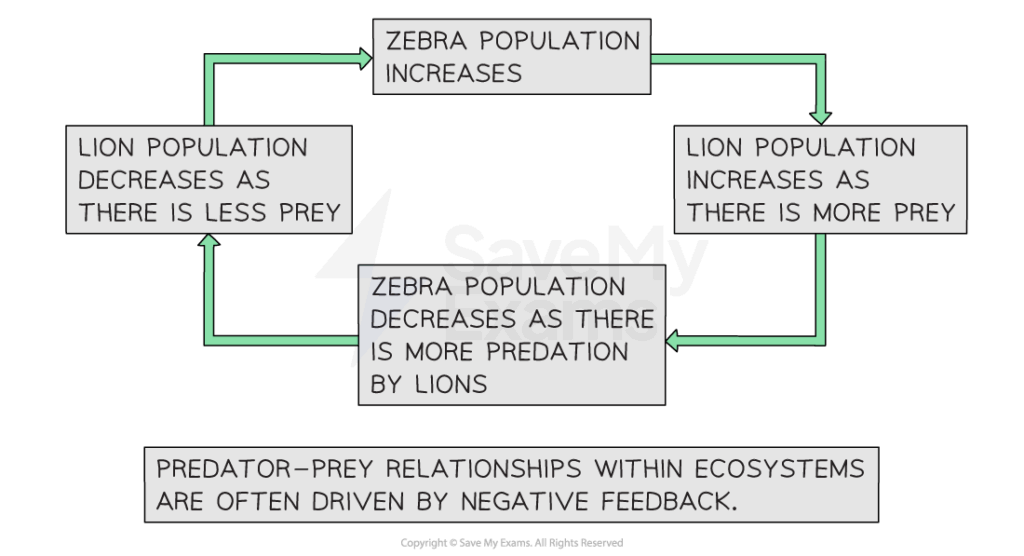

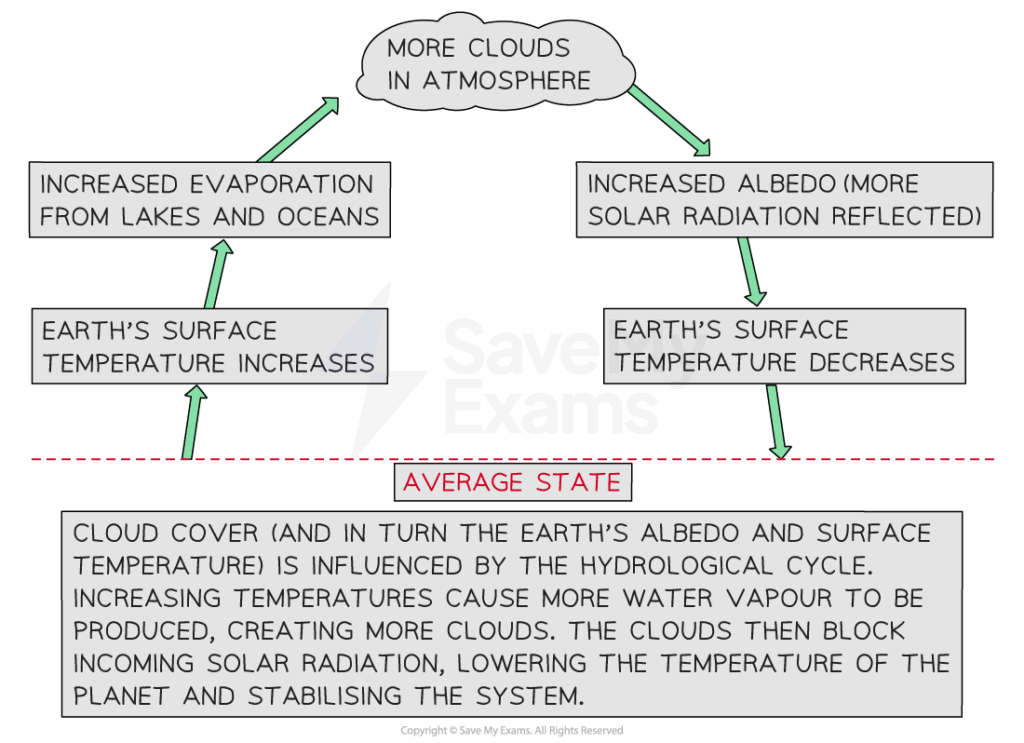

- Negative feedback is any mechanism in a system that counteracts a change away from the equilibrium

- Negative feedback loops occur when the output of a process within a system inhibits or reverses that same process, in a way that brings the system back towards the average state

- In this way, negative feedback is stabilizing – it counteracts deviation from the equilibrium

- Negative feedback loops stabilize systems

Image source: savemyexams.com

Examples of negative feedback include predator-prey relationships and parts of the hydrological cycle

Positive Feedback

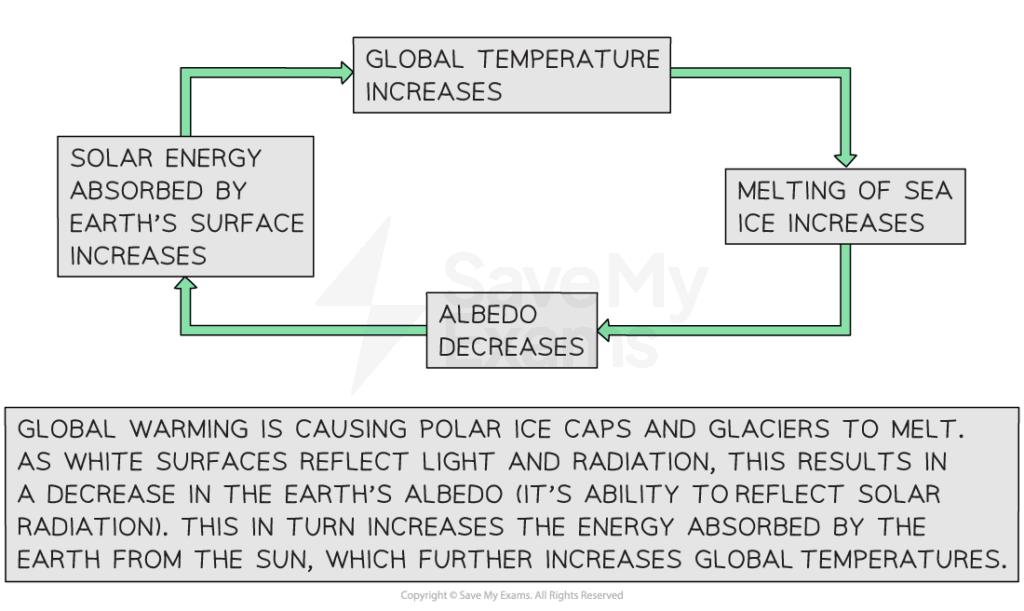

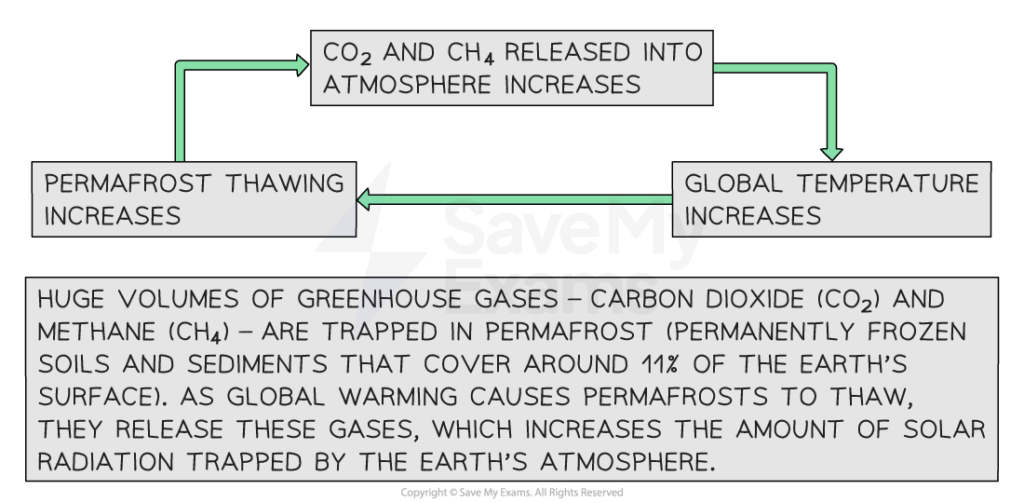

- Positive feedback is any mechanism in a system that leads to additional and increased change away from the equilibrium

- Positive feedback loops occur when the output of a process within a system feeds back into the system, in a way that moves the system increasingly away from the average state

- In this way, positive feedback is destabilizing – it amplifies deviation from the equilibrium and drives systems towards a tipping point where the state of the system suddenly shifts to a new equilibrium

- Positive feedback loops destabilize systems

Image source: savemyexams.com

Other examples of positive feedback:

- Positive feedback loops amplify changes within a system

- They can lead to either an increase or a decrease in a system component.

- Example: population decline

- Population decline reduces reproductive potential

- Reduced reproductive potential further decreases the population

- This amplifying loop accelerates the decline

- Example: population growth

- Population growth increases reproductive potential

- Increased reproductive potential triggers further population growth

- This positive feedback loop accelerates population expansion

📌 Tipping points and Resilience

Tipping Points

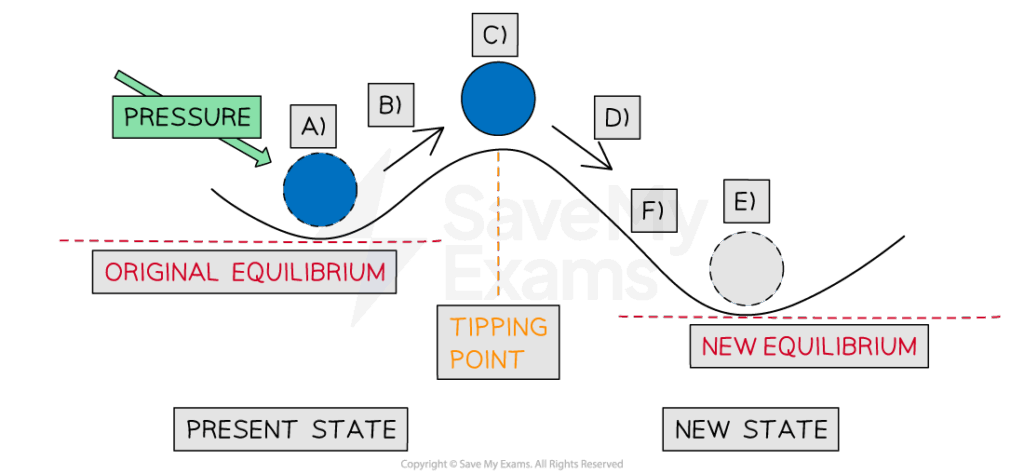

- A tipping point is a critical threshold within a system

- If a tipping point is reached, any further small change in the system will have significant knock-on effects and cause the system to move away from its average state (away from the equilibrium)

- In ecosystems and other ecological systems, tipping points are very important as they represent the point beyond which serious, irreversible damage and change to the system can occur

- Positive feedback loops can push an ecological system towards and past its tipping point, at which point a new equilibrium is likely to be reached

- Eutrophication is a classic example of an ecological reaching a tipping point and accelerating towards a new state

- Tipping points can be difficult to predict for the following reasons:

- There are often delays of varying lengths involved in feedback loops, which add to the complexity of modeling systems

- Not all components or processes within a system will change abruptly at the same time

- It may be impossible to identify a tipping point until after it has been passed

- Activities in one part of the globe may lead to a system reaching a tipping point elsewhere on the planet (e.g. the burning of fossil fuels by industrialized countries is leading to global warming, which is pushing the Amazon basin towards a tipping point of desertification) – continued monitoring, research and scientific communication is required to identity these links

Image source: savemyexams.com

(A) The system is subject to a pressure that pushes it towards a tipping point. (B) The system’s tipping point (critical threshold) is reached. Like a ball balancing on a hill, at this stage even a minor push is enough to cross the tipping point, upon which positive feedback loops accelerate the shift (D) into a new state (E). The change to the new state is often irreversible or a high cost is required to return the system back to its previous state, which is illustrated in the figure as a ball being in a deep valley (E) with a long uphill climb back to the previous state (F)

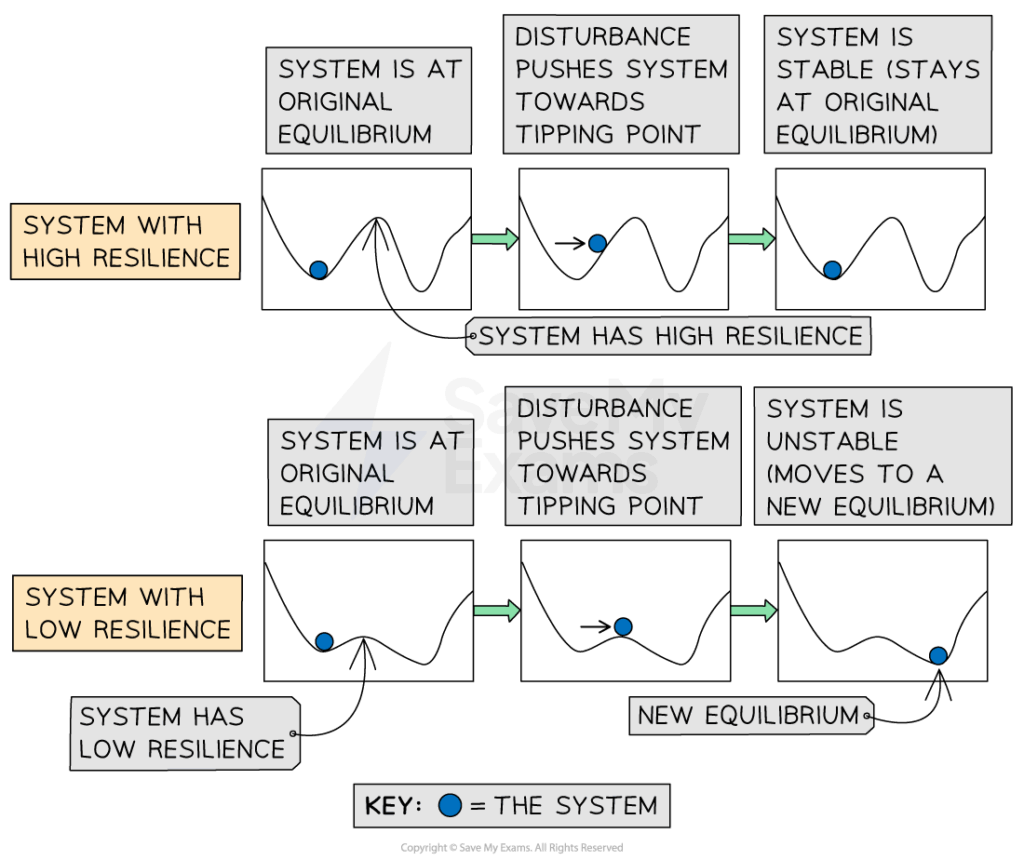

Resilience

- Any system, ecological, social or economic, has a certain amount of resilience

- This resilience refers to the system’s ability to maintain stability and avoid tipping points

- Diversity and the size of storages within systems can contribute to their resilience and affect their speed of response to change

- Systems with higher diversity and larger storages are less likely to reach tipping points

- For example, highly complex ecosystems like rainforests have high diversity in terms of the complexity of their food webs

- If a disturbance occurs within one of these food webs, the animals and plants have many different ways to respond to the change, maintaining the stability of the ecosystem

- Rainforests also contain large storages in the form of long-lived tree species and high numbers of dormant seeds

- These factors promote a steady-state equilibrium in ecosystems like rainforests

- In contrast, agricultural crop systems are artificial monocultures meaning they only contain a single species. This low diversity means they have low resilience – if there is a disturbance to the system (e.g. a new crop disease or pest species), the system will not be able to counteract this

Image source: savemyexams.com

A system with high resilience (such as a tropical rainforest) has a greater ability to avoid tipping points than a system with low resilience (such as an agricultural monoculture)

- Humans can affect the resilience of natural systems by reducing the diversity contained within them and the size of their storages

- Rainforest ecosystems naturally have very high biodiversity

- When this biodiversity is reduced, through the hunting of species to extinction or the destruction of habitat through deforestation, the resilience of the rainforest ecosystem in reduced – it becomes increasingly vulnerable to further disturbances

- Natural grasslands have high resilience, due to large storages of seeds, nutrients and root systems underground, allowing them to recover quickly after a disturbance such as a fire (especially if they contain a diversity of grassland species, including some which are adapted to regenerate quickly after fires)

- However, when humans convert natural grasslands to agricultural crops, the lack of diversity and storages (e.g. no underground seed reserves) results in a system that has low resilience to disturbances such as fires.

📌 Models

- A model is a simplified version of reality and can be used to understand how a system works and predict how it will respond to change.

- A model inevitably involves some approximation and loss of accuracy.

Strengths and Limitations of Models

| Strengths | Limitations |

| Models simplify complex systems | Models can be oversimplified and inaccurate |

| Models allow predictions to be made about how systems will react in response to change | Results from models depend on the quality of the data inputs going into them |

| System inputs can be changed to observe effects and outputs, without the need to wait for real-life events to occur | Results from models become more uncertain the further they predict into the future |

| Models are easier to understand than the real system | Different models can show vastly different outputs even if they are given the same data inputs |

| Results from models can be shared between scientists, engineers, companies and communicated to the public | Results from models can be interpreted by different people in different ways |

| Results from models can warn us about future environmental issues and how to avoid them or minimize their impact | Environmental systems are often incredibly complex, with many interacting factors – it is impossible to take all possible variables into account |