B4.1.1 – ADAPTATIONS FOR TEMPERATURE REGULATION

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Thermoregulation | The ability of an organism to maintain a stable internal body temperature within a tolerable range despite external fluctuations. |

| Endotherm | An organism (e.g., mammals, birds) that maintains body temperature mainly via internal metabolic heat. |

| Ectotherm | An organism (e.g., reptiles, amphibians) whose body temperature depends largely on external heat sources. |

| Homeostasis | Regulation of internal conditions (temperature, water, pH) to maintain equilibrium within cells and organs. |

| Behavioural adaptation | An action by an organism to regulate temperature (e.g., basking, burrowing, nocturnal activity). |

| Physiological adaptation | Internal processes (e.g., sweating, shivering, vasodilation) that maintain temperature balance. |

📌Introduction

Temperature strongly influences metabolic processes by altering enzyme activity and membrane stability. Organisms therefore require adaptations to cope with extremes, whether conserving heat in polar regions or avoiding overheating in deserts. Animals achieve this through combinations of structural, behavioural, and physiological mechanisms. Endotherms regulate temperature using metabolic energy, while ectotherms depend on environmental heat, showing contrasting strategies. Thermoregulation not only aids survival but also shapes ecological niches and evolutionary success.

📌 Endotherms and Ectotherms

- Endotherms:

- Maintain constant internal temperature (around 37–40 °C in mammals).

- Generate heat through metabolic processes (respiration, shivering, non-shivering thermogenesis).

- High energy cost requires frequent food intake.

- Ectotherms:

- Depend on external heat sources; body temperature fluctuates with environment.

- Basking in sunlight or seeking shade regulates body heat.

- Low energy cost, but activity restricted to favourable conditions.

- Trade-offs: independence and activity in all climates (endotherms) versus energy efficiency but dependency on environment (ectotherms).

🧠 Examiner Tip: Don’t just define endotherms and ectotherms — always link to energy costs versus ecological flexibility.

📌 Adaptations to Cold Environments

- Structural: thick fur, blubber, and small extremities (Allen’s Rule) reduce heat loss.

- Physiological: shivering generates metabolic heat, while brown adipose tissue produces heat without shivering.

- Countercurrent heat exchange in blood vessels conserves core heat while limiting loss from extremities.

- Behavioural: huddling (penguins), burrowing, and seasonal migration reduce exposure.

- Seasonal adjustments include moulting into thicker coats or accumulating fat before winter.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: An investigation could compare insulation efficiency in materials mimicking animal fur or blubber (e.g., fat vs wool vs feathers in ice-water experiments).

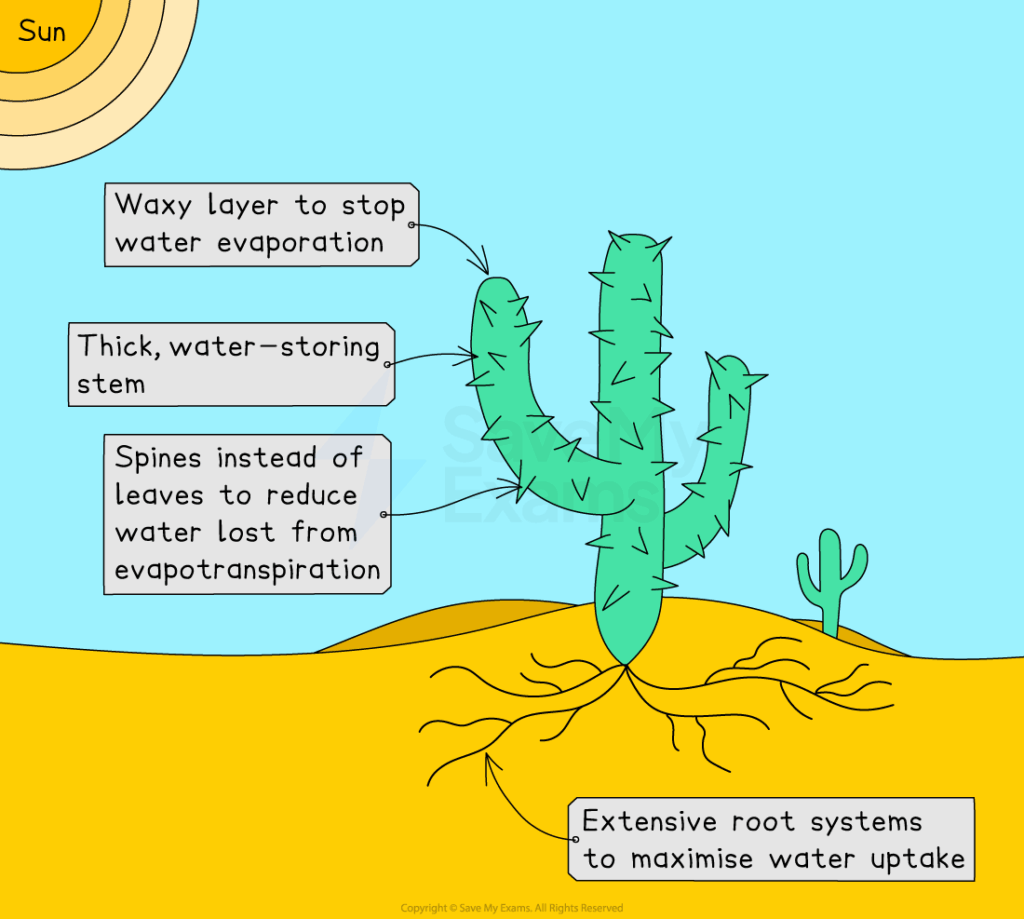

📌 Adaptations to Hot Environments

- Structural: large ears (desert fox), thin fur, and pale colouring increase heat dissipation.

- Physiological: sweating, panting, and vasodilation release heat. Some animals tolerate higher core temperatures to reduce water loss.

- Behavioural: nocturnal activity avoids daytime heat; burrowing or shade-seeking reduces exposure.

- Desert mammals like camels store fat in humps to reduce insulation and conserve water.

- Evaporative cooling strategies are balanced against water conservation needs.

🌐 EE Focus: A possible EE could explore thermoregulation in desert vs polar animals, linking structural features (fur density, ear size) to energy expenditure.

📌 Behavioural and Seasonal Adaptations

- Daily cycles: basking, huddling, or seeking shade align activity with optimal temperature ranges.

- Seasonal cycles: migration (birds), hibernation (bears), or aestivation (amphibians) reduce stress from extreme temperatures.

- Nesting and burrowing behaviours create microhabitats with stable conditions.

- Symbiotic behaviours, such as clustering in colonies, improve group survival in extreme conditions.

❤️ CAS Link: A CAS project could involve creating awareness campaigns about local wildlife adaptations, e.g., how urban animals (dogs, birds) cope with heatwaves.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Human technologies mimic natural thermoregulation — insulated clothing, evaporative cooling systems, and architectural designs draw inspiration from animals adapted to extreme environments.

📌 Extreme Physiological Strategies

- Torpor: temporary lowering of metabolic rate to conserve energy during cold nights (e.g., hummingbirds).

- Hibernation: long-term torpor during winter to reduce energy demands.

- Aestivation: dormancy during hot, dry seasons (snails, amphibians).

- Heat-shock proteins protect cellular structures when organisms experience sudden temperature spikes.

- Acclimatisation: gradual physiological adjustment to seasonal or altitude-related temperature changes.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Thermoregulation highlights reductionist models (heat loss equations, energy balance) versus holistic perspectives (behaviour, ecosystems). TOK question: do simple models of heat balance adequately represent survival in complex natural environments?