B3.3.1 – ADAPTATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS FOR MOVEMENT

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Motile organism | Organism capable of moving from one place to another (e.g., animals, many bacteria). |

| Sessile organism | Organism fixed in place but capable of limited internal or part movement (e.g., plants, sponges). |

| Skeleton | Rigid structure (endo- or exoskeleton) that provides support, protection, and anchorage for muscles. |

| Antagonistic muscles | Pairs of muscles that work in opposite directions at a joint (one contracts while the other relaxes). |

| Synovial joint | A freely movable joint containing synovial fluid that reduces friction and allows varied movement. |

| Lever system | System in which bones act as levers, joints as fulcrums, and muscles provide effort to move loads. |

📌Introduction

Movement is a defining feature of life, ranging from internal cytoplasmic streaming to large-scale locomotion in animals. Motile organisms rely on muscular and skeletal systems for movement, while sessile organisms, such as plants, adapt movement for growth or orientation. Effective locomotion requires three components: muscles for generating force, a skeleton (endo- or exoskeleton) for support and leverage, and joints for flexibility. Adaptations in these systems allow organisms to perform specialized functions such as feeding, escaping predators, or migration.

📌 Motile vs Sessile Adaptations

- Motile organisms: move actively from one place to another. Examples include animals that swim, fly, or walk. Even single-celled motile bacteria use flagella or cilia for propulsion.

- Sessile organisms: fixed in place but capable of movement in parts. Plants orient stems to sunlight (phototropism), while sponges filter water by moving flagella.

- Some organisms combine both traits — corals are sessile as adults but motile as larvae.

- These adaptations reflect ecological niches and energy trade-offs between mobility and anchorage.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Be ready with one motile and one sessile example for exams (e.g., human vs sponge). Simply stating “plants are sessile” is not enough — you must give examples of movement such as tropisms or cytoplasmic streaming.

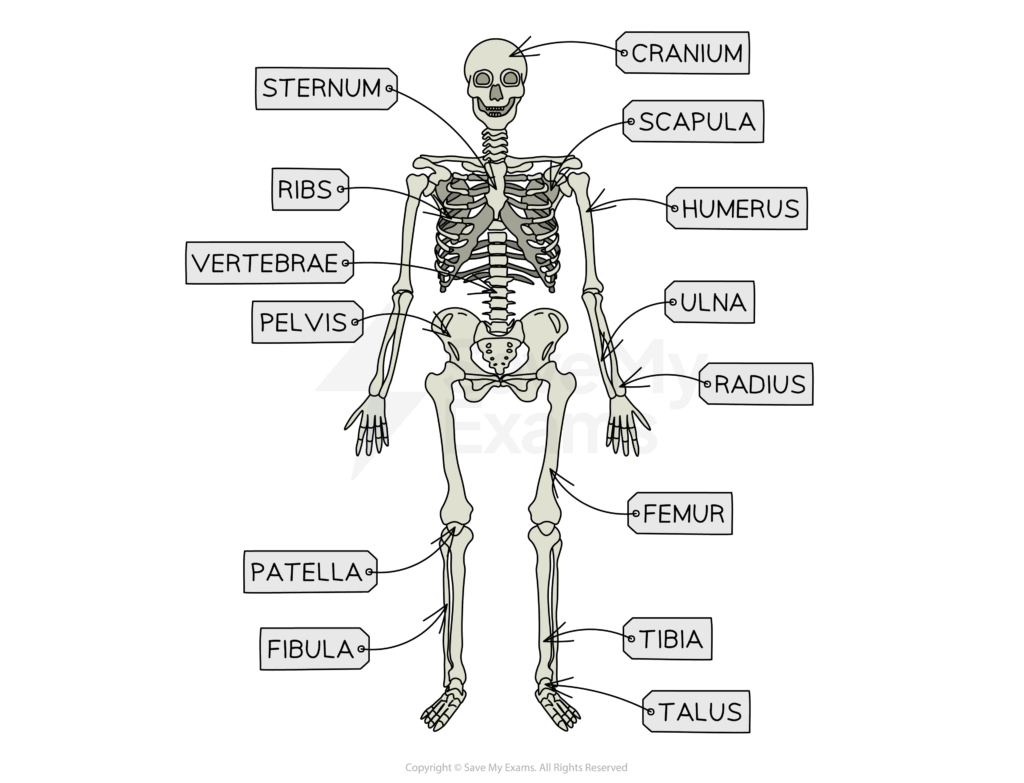

📌 Role of Skeletons in Movement

- Skeletons provide anchorage points for muscles, leverage for force application, and protection for soft tissues.

- Endoskeletons (vertebrates): internal support structure of bone and cartilage; grow with the organism.

- Exoskeletons (arthropods, mollusks): external support made of chitin or calcium carbonate; provide protection but require molting for growth.

- Both systems use joints as fulcrums and muscles as effectors to generate directional force.

- Skeletons act as lever systems:

- Bones = levers.

- Joints = fulcrums.

- Muscles = effort.

- Load = weight moved.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students can model lever systems using bones, joints, and weights to measure mechanical advantage. Comparative studies of insect exoskeletons vs vertebrate bones could illustrate structural adaptations.

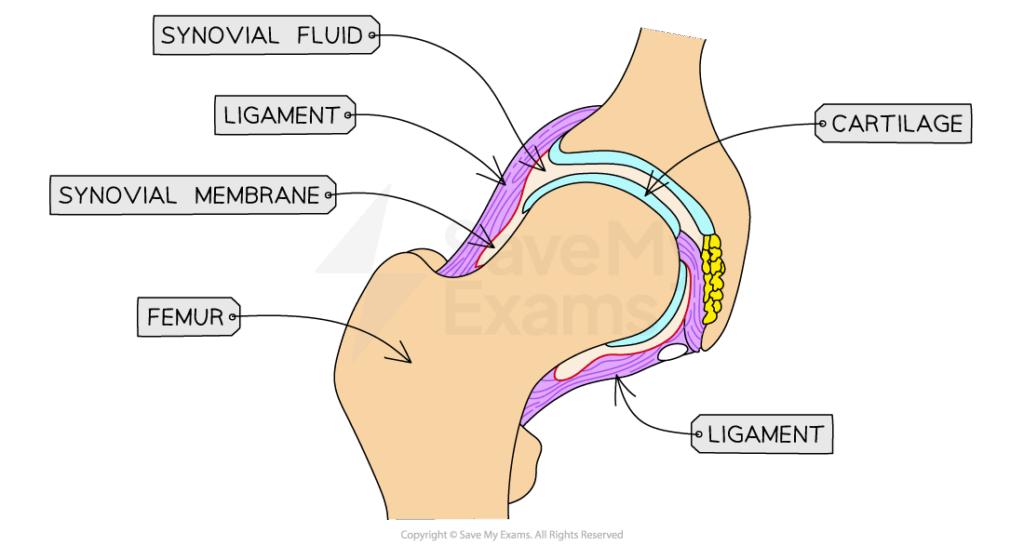

📌 Synovial Joints and Movement

- Synovial joints are the most mobile joints in the human body.

- Components:

- Cartilage covers bone ends, preventing wear.

- Synovial fluid lubricates the joint, reducing friction.

- Ligaments hold bones together while allowing flexibility.

- Tendons attach muscles to bones, transmitting force.

- Types of synovial joints:

- Hinge joints (knee, elbow) → flexion and extension.

- Ball-and-socket joints (hip, shoulder) → flexion, extension, rotation, abduction, adduction.

- These joints allow a wide range of locomotor activities, from running to grasping.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could explore biomechanics of joint movement, such as comparing mechanical efficiency of human hinge vs ball-and-socket joints or investigating how cartilage degeneration affects mobility in arthritis.

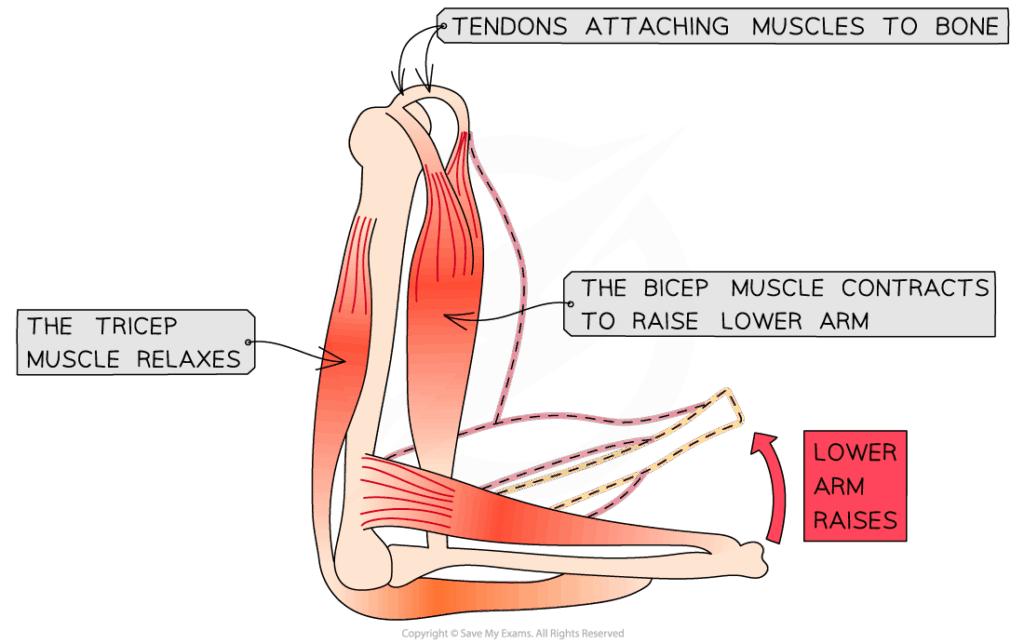

📌 Antagonistic Muscles

- Muscles work in pairs because they can only contract, not push.

- Antagonistic action: one contracts (agonist) while the other relaxes (antagonist).

- Examples:

- Biceps and triceps at the elbow joint (biceps flex, triceps extend).

- Internal and external intercostal muscles in breathing.

- Antagonistic pairs provide control, precision, and flexibility of movement.

- Elastic proteins like titin contribute to restoring sarcomere shape and preventing overstretching.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design fitness sessions demonstrating antagonistic muscle pairs (biceps/triceps, quadriceps/hamstrings), linking exercise science to community health and well-being.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Understanding skeletons and joints underpins medicine (orthopedics, prosthetics), sports science, and robotics. Artificial joints replicate synovial joint properties. Exoskeleton technology is now applied in rehabilitation and industry to assist human movement.

📌 Integration of Movement Systems

- Movement requires cooperation of skeletal system (support and leverage), muscular system (force generation), and nervous system (coordination).

- Adaptations vary: birds have lightweight skeletons for flight, cheetahs have flexible spines for speed, fish have streamlined bodies and fin structures for swimming.

- Such adaptations show how evolution shapes movement efficiency for ecological success.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Movement studies rely heavily on biomechanical models that simplify complex interactions of muscles, bones, and joints. TOK reflection: To what extent do simplified mechanical models capture the reality of biological motion?