B3.2.1 – TRANSPORT IN PLANTS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Xylem | Vascular tissue that transports water and dissolved minerals upward from roots to leaves. |

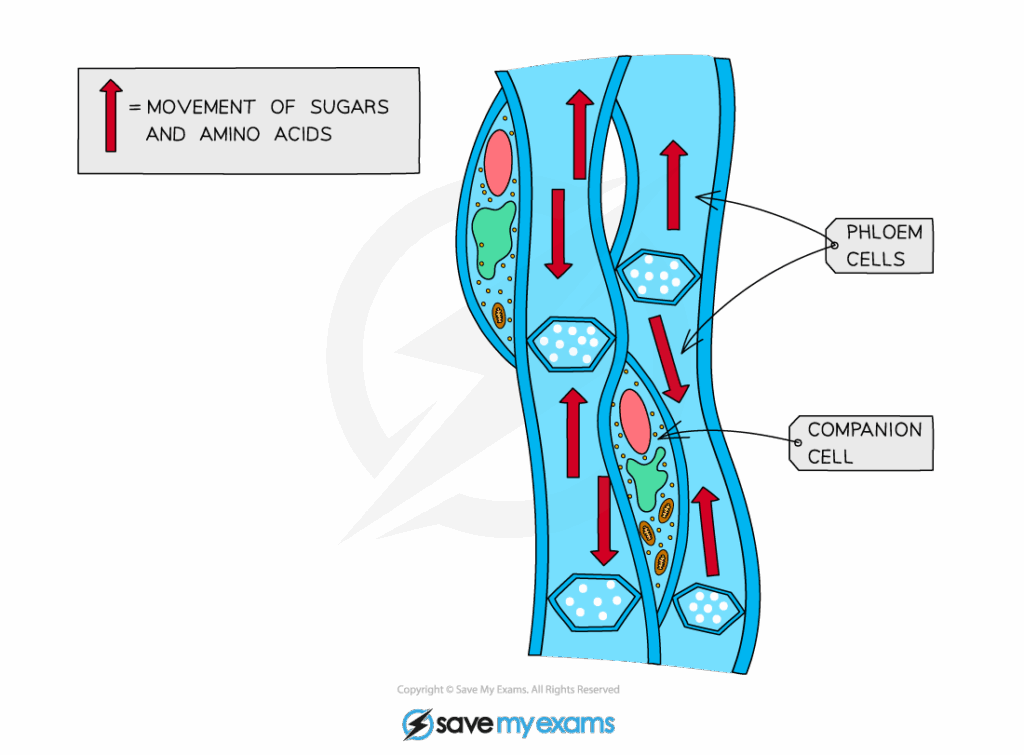

| Phloem | Vascular tissue that transports organic compounds (mainly sucrose) bidirectionally. |

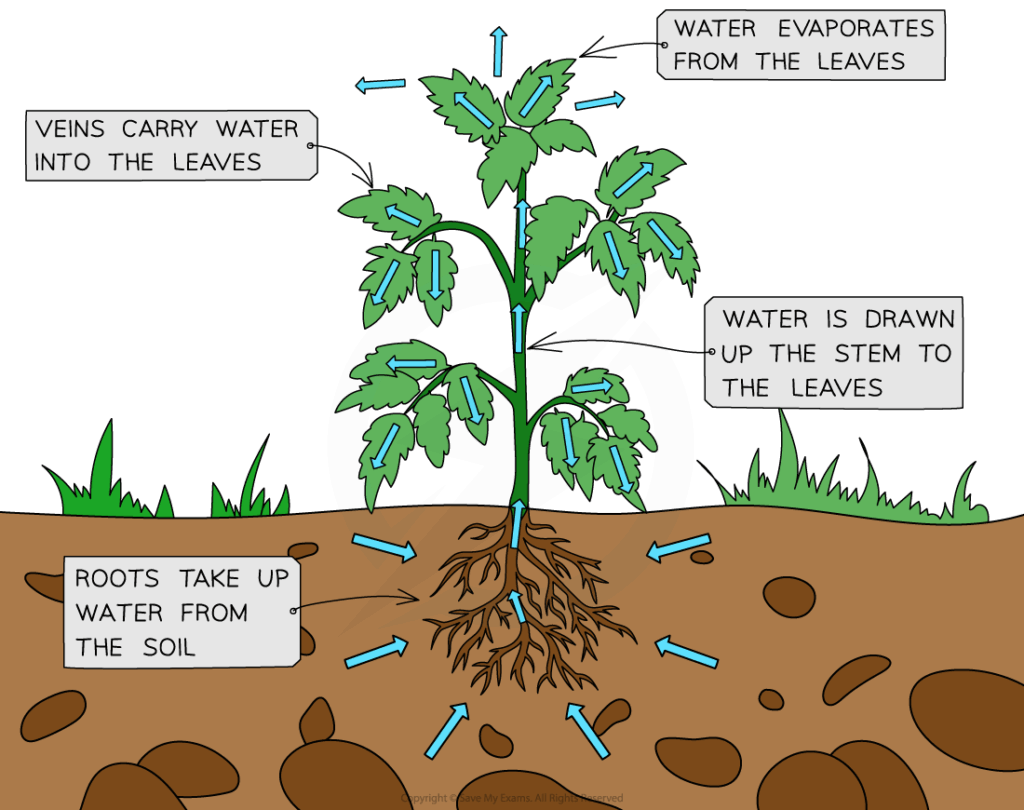

| Transpiration | Evaporation of water from leaf surfaces, driving water uptake through xylem. |

| Cohesion–tension theory | Model explaining how hydrogen bonding between water molecules and adhesion to xylem walls enables upward water transport. |

| Translocation | The movement of sugars and other organic compounds in phloem, from sources (e.g., leaves) to sinks (e.g., roots, fruits). |

| Companion cell | Phloem cell that actively loads sucrose into sieve tubes via ATP-driven transport. |

📌Introduction

Transport in plants is essential for distributing water, minerals, and organic nutrients to all tissues. While diffusion and osmosis are sufficient for unicellular organisms, multicellular plants evolved vascular systems — xylem for water and minerals, and phloem for photosynthates. These systems ensure efficient long-distance transport, even in tall trees. The cohesion–tension model explains how transpiration drives upward water flow, while the pressure-flow hypothesis explains phloem transport. Understanding these processes links molecular interactions like hydrogen bonding to ecological phenomena such as global water cycling.

📌 Xylem Structure and Water Transport

- Xylem vessels are elongated, dead cells aligned end to end, forming continuous tubes.

- Thickened lignin walls prevent collapse under tension and provide structural support.

- Water moves upward by:

- Cohesion: hydrogen bonding between water molecules keeps them connected.

- Adhesion: water sticks to hydrophilic xylem walls, aiding capillarity.

- Transpiration pull: evaporation from stomata creates negative pressure, pulling water upward.

- This passive process requires no metabolic energy from plants.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always state that water transport in xylem is a passive process driven by transpiration and cohesion–tension, not by pumping or active forces.

📌 Phloem Structure and Sugar Transport

- Phloem consists of sieve tube elements (lacking nuclei and ribosomes) supported by companion cells.

- Companion cells actively load sucrose using ATP and proton pumps, creating high solute concentration.

- This lowers water potential, drawing water into sieve tubes by osmosis.

- Hydrostatic pressure builds at sources (e.g., leaves) and pushes phloem sap toward sinks (e.g., roots, fruits, storage organs).

- This mechanism is called the pressure-flow hypothesis.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Experiments can include measuring transpiration with a potometer under varying humidity, temperature, or wind conditions. For phloem, aphid stylet experiments can demonstrate direction and composition of translocation.

📌 Regulation of Transport in Plants

- Stomata control transpiration by regulating gas exchange. Guard cells respond to light, CO₂, and water availability.

- Environmental factors (humidity, temperature, wind, light) influence transpiration rate.

- Seasonal changes affect transport — sugars flow to roots in winter and toward shoots/flowers in spring.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how environmental conditions (light intensity, humidity, CO₂ levels) influence transpiration rates, or how different plant adaptations (xerophytes vs hydrophytes) alter vascular transport efficiency.

📌 Plant Adaptations for Transport

- Xerophytes: reduced leaf area, thick cuticles, sunken stomata to minimize water loss.

- Hydrophytes: large air spaces for buoyancy, stomata on upper surfaces, reduced vascular tissue.

- Halophytes: salt glands, succulence, and selective ion transport to survive in saline environments.

- These adaptations link plant transport physiology to survival in diverse habitats.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could build simple potometer models and present findings on plant water use efficiency to promote sustainable agriculture or gardening in their communities.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Knowledge of plant transport underpins agriculture and forestry. Drought-resistant crop breeding focuses on xylem efficiency. Sugarcane productivity depends on optimizing phloem translocation. Global climate change threatens transpiration cycles, with direct impacts on ecosystems and water availability.

📌 Applications of Plant Transport

- Explains how water and minerals reach leaves for photosynthesis.

- Provides the basis for sugar movement into fruits, essential in agriculture.

- Connects cellular-level hydrogen bonding to ecosystem-level water cycling.

🔍 TOK Perspective: The cohesion–tension theory relies on indirect evidence, since we cannot directly “see” water columns in xylem. TOK reflection: How do models built on indirect evidence shape our confidence in scientific explanations?