B2.3.2 – CELL SPECIALISATION AND CONSTRAINTS ON CELL SIZE

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cell specialisation | The process by which generic cells develop specific structures and functions suited to a particular role. |

| Cell differentiation | The molecular and structural changes that convert a stem cell into a specialised cell type. |

| Constraints on cell size | The physical and functional limitations that restrict how large or small a cell can be, often linked to surface area-to-volume ratio. |

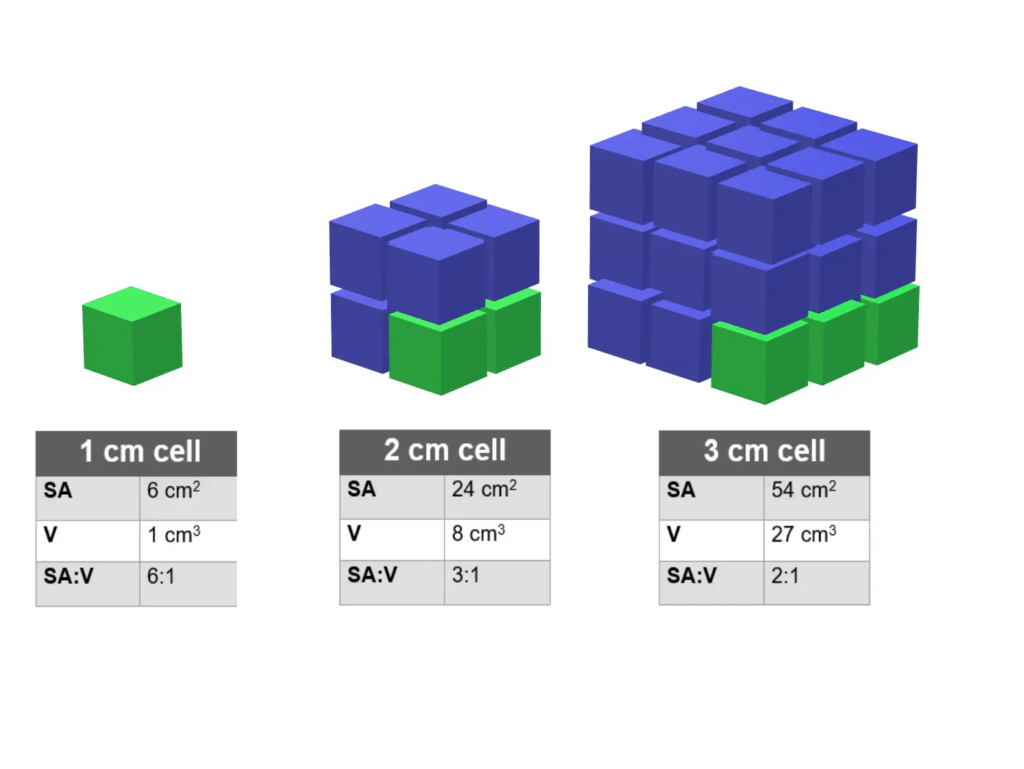

| SA:V ratio | The ratio of surface area to volume, which determines how efficiently a cell can exchange materials with its environment. |

| Diffusion limit | The point at which a cell becomes too large for diffusion alone to supply its metabolic needs. |

📌Introduction

Cells in multicellular organisms rarely remain identical. Instead, they differentiate into specialised types, enabling the organism to function as an integrated whole. Specialisation improves efficiency but reduces flexibility, meaning cells become committed to particular roles. At the same time, cells face physical limits on their size. The relationship between surface area and volume sets constraints: as cells grow larger, their volume increases faster than their surface area, reducing their ability to exchange materials effectively. These constraints influence why cells remain microscopic, why large organisms consist of many cells rather than fewer giant cells, and why specialisation is necessary for survival.

📌 Cell Specialisation in Multicellular Organisms

- Specialisation allows cells to perform tasks more efficiently than if every cell attempted to perform all functions.

- Examples include neurons transmitting impulses rapidly, muscle cells contracting for movement, and epithelial cells forming protective barriers.

- Specialisation is achieved through differential gene expression, where only certain genes are activated in a given cell type, producing unique proteins.

- The process is irreversible for most cells, locking them into a single role once differentiated.

- Cell specialisation contributes to division of labour within tissues and organs, enhancing survival and adaptation in complex organisms.

🧠 Examiner Tip: When explaining cell specialisation, don’t just list examples. Always connect the structural adaptations of a cell to its specific role (e.g., red blood cells lack a nucleus to maximise haemoglobin content for oxygen transport).

📌 Constraints on Cell Size

- The SA:V ratio decreases as a cell grows larger, meaning less surface area is available per unit volume for exchange.

- Smaller cells can exchange gases, nutrients, and wastes more efficiently because of their relatively larger SA:V ratio.

- If a cell grows too large, diffusion distances become too great, and the centre of the cell may not receive materials quickly enough.

- Cells overcome this limitation by adopting shapes that maximise surface area (e.g., microvilli in epithelial cells) or by compartmentalisation with organelles.

- Multicellular organisation evolved partly as a response to this constraint, allowing organisms to grow large while individual cells remain small.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: A classic practical is using agar blocks impregnated with an indicator like phenolphthalein to simulate diffusion in cells. Students can measure how surface area-to-volume ratio affects diffusion rates, linking results to real cellular constraints

📌 Adaptations to Overcome Size Constraints

- Flattened or elongated shapes (e.g., red blood cells, nerve cells) increase surface area relative to volume.

- Internal transport systems such as the cytoskeleton and endomembrane system help move substances efficiently within larger cells.

- Compartmentalisation within organelles allows localised conditions that improve efficiency despite size.

- In multicellular organisms, specialised transport systems (e.g., circulatory system) evolve to supply large numbers of cells with nutrients and oxygen.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how different SA:V ratios influence metabolic rates across organisms of different sizes, or compare adaptations to overcome diffusion limits in unicellular vs multicellular organisms.

📌 Integration of Specialisation and Constraints

- The limits on cell size partly explain why cells differentiate — they cannot “do everything” while remaining efficient.

- Division of labour in tissues offsets size constraints, as no single cell must maintain every function.

- This balance shows how biology integrates physical limits with evolutionary solutions.

❤️ CAS Link: A CAS project could involve designing classroom demonstrations using models of cells with different SA:V ratios, showing younger students why cells remain small and why organisms need specialised cells.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Cancer cells often lose their specialisation and revert to uncontrolled growth, ignoring normal constraints. Understanding SA:V ratio is also critical in biotechnology, such as designing artificial tissues where nutrient diffusion is a limiting factor.

📌 Specialisation vs Flexibility

- While specialisation enhances efficiency, it reduces flexibility: most specialised cells cannot divide or change role.

- Stem cells remain unspecialised to balance this limitation, ensuring long-term tissue maintenance.

- Constraints on cell size reinforce the need for cooperative multicellularity and specialisation.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Cell size and specialisation highlight how physical laws (like SA:V ratios) constrain biological possibilities. TOK questions emerge about determinism: to what extent does biology innovate freely, and to what extent is it limited by fundamental physical principles?