B2.1.2 – MEMBRANE TRANSPORT

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Diffusion | Passive movement of molecules from a region of high concentration to low concentration due to random motion. |

| Facilitated diffusion | Passive movement of molecules across a membrane through specific channel or carrier proteins. |

| Osmosis | Passive diffusion of water molecules across a selectively permeable membrane, from low solute concentration to high solute concentration. |

| Active transport | Movement of molecules against their concentration gradient using energy, typically ATP. |

| Endocytosis | Active process where the membrane engulfs material to bring it into the cell, forming vesicles. |

| Exocytosis | Active process where vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane to release contents outside the cell. |

📌Introduction

Transport across membranes is vital for maintaining homeostasis, enabling nutrient uptake, waste removal, signal transduction, and energy conversion. Membranes are selectively permeable, meaning only certain molecules can pass freely, while others require assistance. Cells exploit both passive and active processes, as well as bulk transport via vesicles, to control their internal environment. Understanding membrane transport explains phenomena ranging from nerve impulse transmission to kidney filtration.

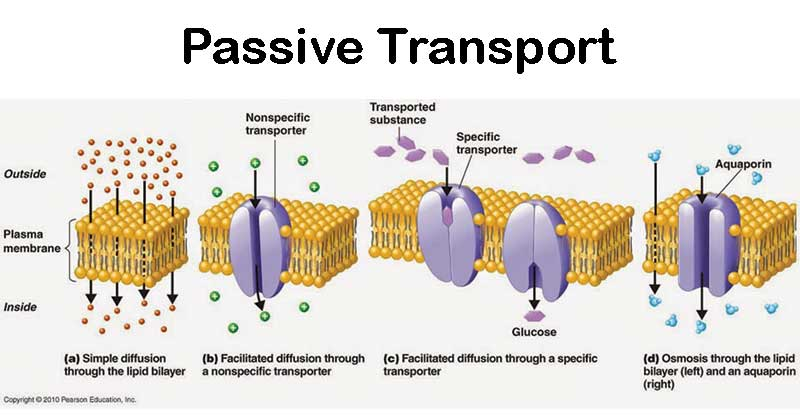

📌 Passive Transport: Diffusion and Osmosis

- Diffusion is the movement of molecules such as oxygen and carbon dioxide across membranes without energy input. The rate of diffusion depends on concentration gradient, temperature, and surface area.

- Facilitated diffusion involves large or charged molecules (e.g., glucose, ions) moving through specific protein channels or carriers. It is still passive because it does not require energy.

- Osmosis is the passive movement of water through aquaporins or directly across the bilayer. Water moves toward regions of higher solute concentration to balance osmotic gradients.

- Osmosis underlies turgor pressure in plants and fluid balance in animals.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always specify the direction of movement relative to solute concentration in osmosis questions, and note that osmosis requires a selectively permeable membrane — not just any barrier.

📌 Active Transport

- Active transport moves molecules against their concentration gradient, requiring energy, usually from ATP hydrolysis.

- Performed by carrier proteins and pumps (e.g., sodium-potassium pump, proton pumps).

- The sodium-potassium pump is essential in nerve conduction: it pumps 3 Na⁺ out and 2 K⁺ in, maintaining electrochemical gradients across the membrane.

- Active transport allows cells to accumulate nutrients, expel waste, and maintain ion gradients essential for processes like respiration and photosynthesis.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Classic IA experiments include measuring osmosis in potato strips placed in solutions of varying sucrose concentration, or modeling active transport using yeast and glucose uptake with inhibitors to show the need for ATP.

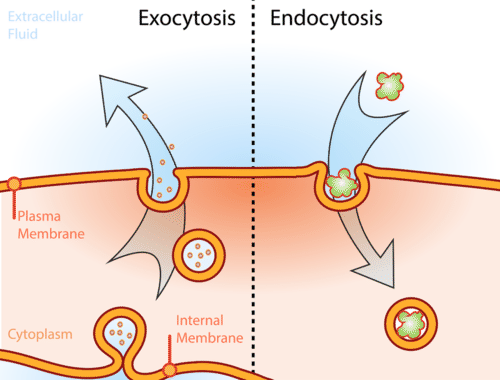

📌 Vesicular Transport: Endocytosis and Exocytosis

- Endocytosis: the membrane surrounds and engulfs material, pinching off into vesicles inside the cell. Types include:

- Phagocytosis (“cell eating”) → ingestion of large particles or cells.

- Pinocytosis (“cell drinking”) → uptake of liquids and solutes.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis → highly specific, e.g., uptake of LDL cholesterol.

- Exocytosis: vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane to secrete substances such as hormones, neurotransmitters, or digestive enzymes.

- Vesicular transport is essential for communication, secretion, and turnover of membrane components.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could investigate how temperature, solute concentration, or inhibitors affect transport processes like diffusion or osmosis, or explore vesicular trafficking in relation to diseases like cystic fibrosis.

📌 Membrane Transport in Specialized Cells

- Nerve cells: rely on sodium-potassium pumps, ion channels, and exocytosis of neurotransmitters for impulse transmission.

- Kidney cells: transport proteins reabsorb glucose, ions, and water from filtrate, demonstrating selective and active transport in physiology.

- Intestinal cells: glucose absorption occurs via sodium-glucose co-transport, combining facilitated diffusion and active transport.

- These examples show how universal mechanisms of transport are adapted for specialized functions.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design an experiment-based workshop for younger peers using osmosis in plant tissues (e.g., potato cores in salt solutions) to demonstrate membrane transport, linking school science to nutrition and hydration awareness.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Many diseases and treatments are based on membrane transport. Cystic fibrosis arises from a defective chloride channel. Diuretics manipulate kidney ion transport to reduce blood pressure. Oral rehydration solutions treat dehydration by exploiting sodium-glucose co-transport. Drug delivery systems often target specific transport mechanisms or vesicular pathways.

📌 Applications of Membrane Transport

- Explains nutrient uptake in the gut and waste removal by kidneys.

- Clarifies how plants maintain water balance through osmosis and transpiration.

- Provides the basis for understanding nerve impulses, muscle contraction, and hormonal secretion.

- In biotechnology, liposomes and vesicles are engineered for targeted drug delivery.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Membrane transport relies on models such as “pump” and “channel,” which simplify dynamic molecular processes. TOK reflection: How do metaphors and models in biology aid understanding while also limiting how we perceive reality?