B2.1.3 – MEMBRANE INTERACTIONS & CELL ADHESION

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cell adhesion | The process by which cells attach to each other or to the extracellular matrix, often via specialized proteins. |

| Tight junction | A type of cell junction that seals neighboring cells together, preventing leakage of molecules between them. |

| Desmosome | Strong, anchoring junctions that link the cytoskeleton of one cell to another, providing mechanical strength. |

| Gap junction | Channels that directly connect the cytoplasm of adjacent cells, allowing exchange of ions and small molecules. |

| Extracellular matrix (ECM) | A network of proteins and polysaccharides outside cells that provides structural and biochemical support. |

| Integrins | Transmembrane proteins that connect the cytoskeleton to the ECM and mediate signaling. |

📌Introduction

Cells do not exist in isolation — they interact constantly with one another and with their surrounding extracellular environment. These interactions are mediated by membrane proteins, adhesion molecules, and structural networks like the extracellular matrix. Through adhesion and communication, cells form tissues, coordinate activities, and respond to environmental changes. Membrane interactions are essential for maintaining tissue integrity, enabling signaling, and ensuring the cooperative behavior of multicellular organisms.

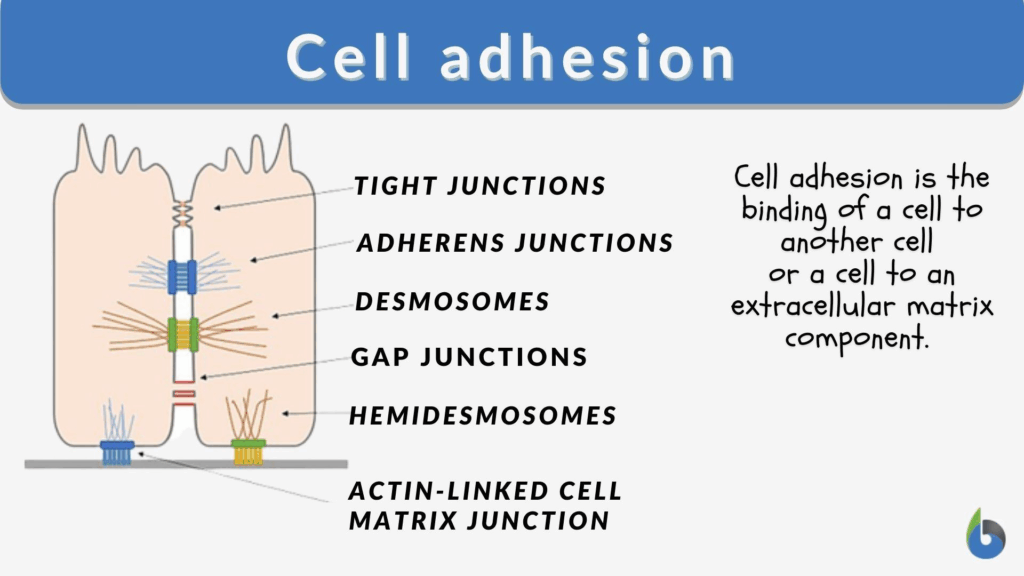

📌 Cell Adhesion and Junctions

- Cells adhere to each other using specialized proteins such as cadherins, integrins, and selectins.

- Tight junctions form continuous seals between epithelial cells, preventing leakage of materials between compartments (e.g., in the intestines or kidneys).

- Desmosomes act like rivets, anchoring intermediate filaments between cells and providing resistance to mechanical stress (e.g., in skin and heart muscle).

- Gap junctions provide direct cytoplasmic connections between neighboring cells, allowing ions and small molecules to pass for rapid communication.

- These junctions enable tissues to function as integrated units, with both structural and communicative properties.

🧠 Examiner Tip: In IB exams, when asked about junctions, link structure to function — e.g., tight junctions “prevent leakage” while gap junctions “allow communication.” Avoid simply listing types without explaining their roles.

📌 Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

- The ECM surrounds animal cells and consists mainly of proteins (collagen, elastin, fibronectin) and polysaccharides (glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans).

- Provides structural support, anchoring cells in place, while also serving as a medium for signaling.

- Integrins connect the ECM to the cytoskeleton, transmitting mechanical and chemical signals that influence cell behavior such as migration, growth, and differentiation.

- ECM composition varies between tissues, tailoring mechanical and biochemical properties to function (e.g., rigidity in bone vs elasticity in cartilage).

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Investigations using simple histology slides can show tissue differences in ECM structure (cartilage vs muscle). Advanced projects could test enzyme digestion of ECM proteins like collagen, linking structure to functional significance.

📌 Cell–Cell Communication Through Membranes

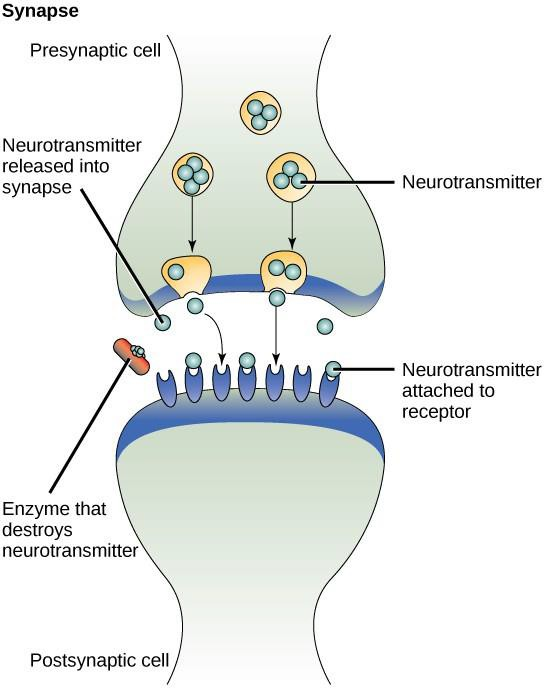

- Membrane proteins act as receptors for hormones, neurotransmitters, and cytokines, enabling cells to detect and respond to external signals.

- Direct communication occurs through gap junctions in animals and plasmodesmata in plants.

- Signal transduction pathways often begin at the membrane with receptor-ligand binding, triggering cascades that alter gene expression or metabolism.

- Effective communication ensures processes like growth, immune response, and tissue repair are coordinated across many cells.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could examine how specific adhesion proteins (e.g., integrins or cadherins) influence cancer progression, or how defects in gap junctions affect heart conduction and neurological diseases.

📌 Role in Tissue Organization

- Adhesion and membrane interactions allow cells to organize into tissues with distinct functions.

- In epithelia, tight junctions maintain polarity by separating apical and basal surfaces.

- In muscle, desmosomes and gap junctions coordinate contraction by linking cytoskeletons and enabling ion flow.

- The ECM guides cell migration during development and wound healing.

- Disruption of adhesion leads to diseases such as blistering disorders (loss of desmosomes) or cancer metastasis (loss of anchoring proteins).

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design a health-awareness project explaining how cancers spread through loss of adhesion, helping communities understand why early detection and treatment are vital.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Defects in membrane interactions are implicated in major diseases. For example, loss of cadherins contributes to cancer metastasis, while mutations in gap junction proteins cause heart arrhythmias and deafness. In regenerative medicine, scaffolds mimicking ECM are used to grow replacement tissues. Adhesion molecules are also targeted in therapies for autoimmune diseases and infections.

📌 Applications of Membrane Interactions

- Understanding adhesion helps explain immune responses, where leukocytes bind to blood vessel walls before migrating into tissues.

- Gap junction studies clarify how heart muscle cells coordinate contraction for pumping blood.

- ECM research underpins biomedical engineering, leading to artificial cartilage, skin grafts, and tissue scaffolds.

- Membrane adhesion principles are used in biotechnology to grow cells in culture for research or drug production.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Membrane interactions show how biology operates at multiple scales — from molecular adhesion to tissue-level behavior. TOK reflection: When studying complex systems like tissues, how do scientists decide the appropriate “level” of knowledge — molecular, cellular, or systemic?