B4.2.2 – INTERACTIONS AND NICHE DIFFERENTIATION

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fundamental niche | The full range of abiotic and biotic conditions under which a species could survive and reproduce in the absence of competition. |

| Realised niche | The actual niche a species occupies, restricted by competition, predation, or other interactions. |

| Competitive exclusion principle | The principle that no two species can indefinitely occupy the same niche when resources are limited; one species will outcompete the other. |

| Niche partitioning | The division of resources among coexisting species to reduce direct competition. |

| Resource overlap | The degree to which species use the same resources, which influences competition intensity. |

| Coevolution | Reciprocal adaptations in interacting species, driving niche differentiation over time. |

📌Introduction

Interactions among species play a central role in shaping niches. While the fundamental niche represents the full potential of a species, biotic interactions often restrict it to a narrower realised niche. Competition, predation, and symbiosis determine how species coexist, and niche partitioning allows multiple species to survive within the same habitat by reducing direct competition. These dynamics not only determine community structure but also influence evolutionary change, as species adapt in response to one another.

📌 Fundamental vs Realised Niches

- The fundamental niche reflects an organism’s full tolerance range for abiotic conditions (e.g., light, salinity, temperature).

- The realised niche is usually narrower, determined by pressures from competitors, predators, or mutualistic partners.

- Example: Barnacle studies (Connell, 1961) show that Chthamalus occupies higher tidal zones due to exclusion from lower zones by Balanus.

- Fundamental niches can expand if competitors are removed, a phenomenon known as competitive release.

- Species with broader realised niches (generalists) cope better with competition than specialists.

- Niche compression occurs when many species overlap in resource use, forcing narrower realised niches to avoid exclusion.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Diagrams of overlapping fundamental vs realised niches often appear in exams. Always label axes (resource gradient, abundance) and state the role of competition in shifting niche boundaries.

📌 Competitive Exclusion Principle

- Gause’s experiments with Paramecium showed that two species competing for identical resources cannot coexist — one will always outcompete the other.

- Competitive exclusion drives ecological separation: species must diverge in behaviour, feeding, or timing to persist.

- This principle underpins the structure of natural communities, ensuring each species occupies a unique ecological role.

- Invasive species often disrupt existing balances by excluding natives from their niches.

- Resource availability and environmental variability can sometimes relax exclusion, allowing coexistence.

- Coexistence is possible if niches are differentiated, but prolonged overlap leads to displacement or extinction of one competitor.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Simple classroom models of competition (yeast, protozoa, or bacterial cultures) can be used to illustrate exclusion and resource limitation. Field transects can also demonstrate displacement patterns between invasive and native plant species.

📌 Niche Partitioning

- Partitioning reduces competition by dividing resources spatially, temporally, or behaviourally.

- Spatial partitioning: Warbler species forage at different levels of the same tree, avoiding direct overlap.

- Temporal partitioning: Nocturnal rodents avoid diurnal competitors, reducing overlap in food access.

- Morphological partitioning: Beak size differences in Darwin’s finches correspond to different seed sizes.

- Partitioning is dynamic — in times of resource scarcity, overlap may increase temporarily.

- Over evolutionary timescales, partitioning can lead to character displacement, where species diverge morphologically or behaviourally.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could test niche partitioning in a local ecosystem, e.g., comparing feeding behaviour of bird species in urban vs rural areas, or analysing pollinator activity patterns over time.

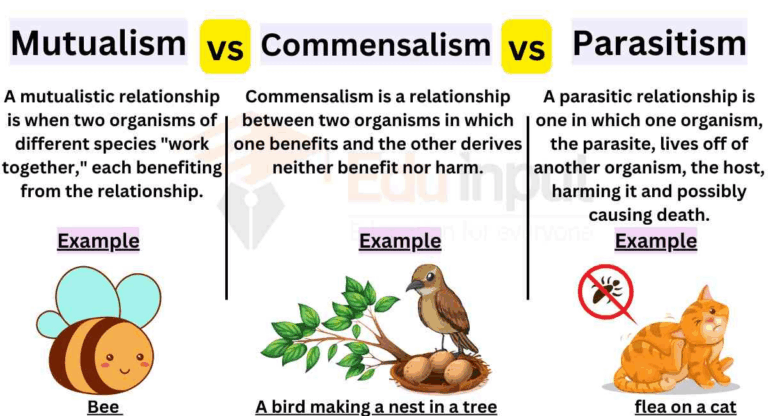

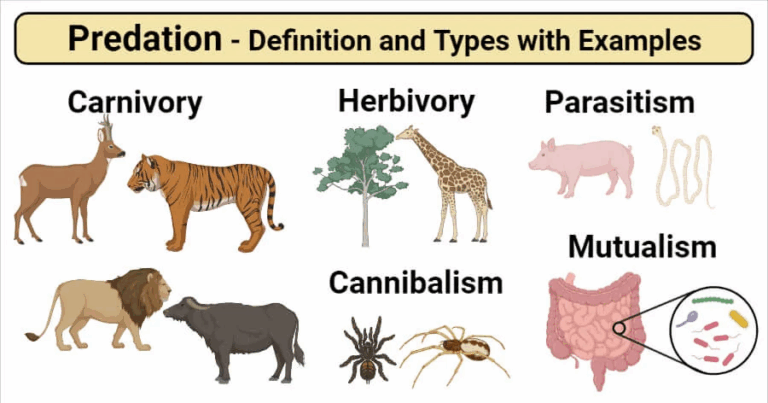

📌 Predator–Prey and Other Interactions

- Predators indirectly shape prey niches by influencing where and when prey forage (“landscape of fear”).

- Prey adapt through camouflage, mimicry, toxins, or behavioural changes (grouping, vigilance).

- Predators also specialise, reducing overlap by targeting distinct prey (e.g., owls vs hawks hunting at night/day).

- Mutualisms (e.g., pollinators and plants) broaden realised niches by creating interdependent resource relationships.

- Parasitism narrows host niches by reducing health, altering feeding or reproductive roles.

- Keystone predators maintain biodiversity by preventing competitive exclusion among prey species.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design interactive workshops explaining predator–prey adaptations with role-play or simulations, helping younger students understand ecological balance.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Conservation strategies often involve protecting predator populations because their removal leads to prey overpopulation, reduced diversity, and niche collapse (e.g., wolves in Yellowstone).

📌 Coevolution and Long-Term Differentiation

- Coevolution occurs when species reciprocally influence each other’s adaptations, leading to niche changes.

- Classic example: flowers and pollinators evolve specialised relationships (long nectar tubes vs long proboscis).

- Predator–prey “arms races” drive adaptations such as faster predators and evasive prey.

- Symbiotic relationships evolve stability — e.g., corals and zooxanthellae share niches through mutual benefits.

- Over long timescales, coevolution can generate biodiversity by diversifying niches.

- Climate change and human disturbance may disrupt these evolved niche relationships, leading to mismatches.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Niche differentiation is often modelled in simplified diagrams of overlap and partitioning. TOK issue: do such reductionist models (e.g., graphs of resource use) obscure the complexity of multi-species interactions in real ecosystems?