B1.2.2 – PROTEIN STRUCTURE AND PROPERTIES

📌Definition Table

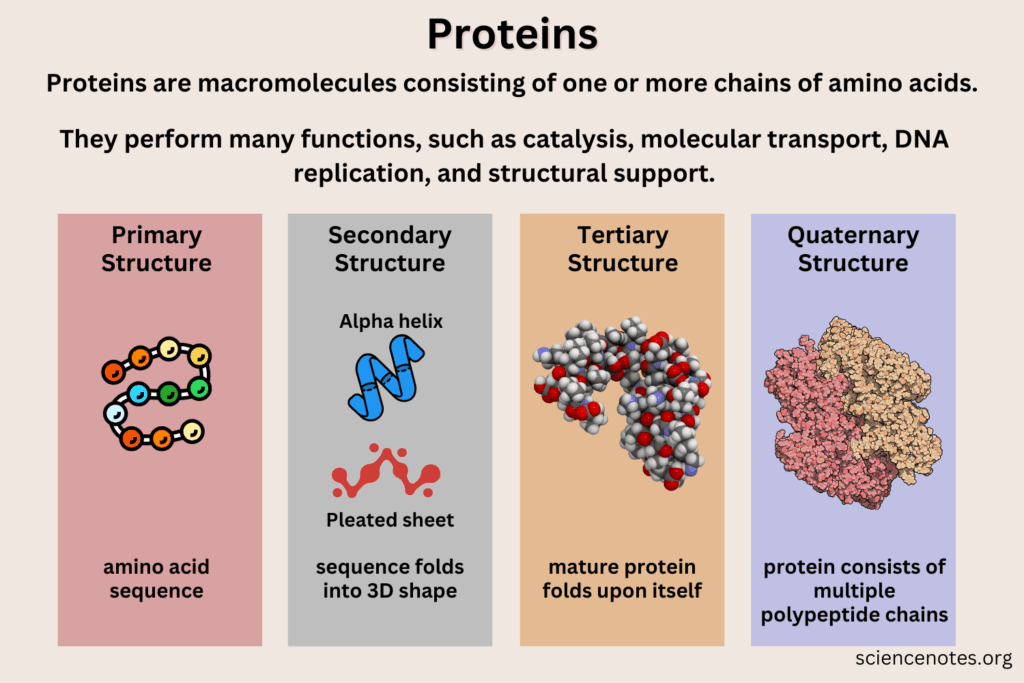

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Primary structure | Linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide, determined by DNA. |

| Secondary structure | Local folding of the polypeptide into α-helices or β-pleated sheets, stabilized by hydrogen bonds. |

| Tertiary structure | Overall 3D shape of a polypeptide, formed by interactions between R groups (hydrophobic, ionic, hydrogen bonds, disulfide bridges). |

| Quaternary structure | Association of multiple polypeptide chains to form a functional protein (e.g., hemoglobin). |

| Denaturation | Loss of protein’s native structure due to heat, pH, or chemicals, leading to loss of function. |

| Fibrous protein | Structural proteins with long, elongated shapes (e.g., collagen, keratin). |

| Globular protein | Compact, spherical proteins that are soluble and functional (e.g., enzymes, hormones). |

📌Introduction

The function of a protein depends critically on its structure. Although all proteins are made from the same 20 amino acids, their folding and organization result in immense structural diversity. The four levels of protein structure — primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary — provide increasing complexity and specificity. Proteins can be fibrous and structural, globular and functional, or even combine features of both. Their unique properties, such as solubility, flexibility, or tensile strength, arise from chemical interactions between amino acid R groups, making protein folding one of the most fascinating aspects of molecular biology.

📌 Primary and Secondary Structure

- The primary structure of a protein is its amino acid sequence, coded by DNA and assembled by ribosomes. Even a single change in sequence can dramatically alter function (e.g., sickle-cell hemoglobin caused by one substitution).

- Secondary structures arise when polypeptide chains coil or fold locally:

- α-helices: right-handed coils stabilized by hydrogen bonds every fourth amino acid.

- β-pleated sheets: parallel or antiparallel strands held by hydrogen bonds, forming rigid structures.

- These recurring motifs provide the backbone of many proteins, contributing to stability and mechanical properties.

🧠 Examiner Tip: When describing secondary structure, explicitly mention hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms (C=O and N–H), not between R groups — this is a common mistake in IB exams.

📌 Tertiary Structure

- The tertiary structure is the unique 3D conformation of a polypeptide, formed by interactions among R groups.

- Key interactions include:

- Hydrogen bonds between polar side chains.

- Ionic bonds between charged R groups.

- Hydrophobic interactions driving nonpolar R groups inward, away from aqueous environments.

- Disulfide bridges, covalent bonds between cysteine residues, providing strong stability.

- Tertiary structure determines the protein’s active site, specificity, and overall function.

- Denaturation disrupts these interactions, causing irreversible loss of shape and function.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Experiments on enzyme activity at different pH or temperatures highlight the effect of tertiary structure disruption. For instance, heating catalase destroys its active site by denaturation, visibly reducing its ability to break down hydrogen peroxide.

📌 Quaternary Structure

- Proteins with multiple polypeptides form quaternary structures, where subunits interact to create a functional protein.

- Example: Hemoglobin, composed of four subunits, each with a heme group that binds oxygen cooperatively.

- Other examples include antibodies (four polypeptide chains) and ion channels made of multiple protein subunits.

- Quaternary structures often enable regulation, stability, and complex functionality not possible with single polypeptides.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could explore the structural basis of enzyme specificity, or how mutations affecting quaternary structure impair function, such as in sickle-cell anemia or prion diseases.

📌 Fibrous vs Globular Proteins

- Fibrous proteins: elongated, insoluble, structural roles. Examples:

- Collagen → provides tensile strength in skin, ligaments, and tendons.

- Keratin → strong protein in hair, nails, and feathers.

- Silk fibroin → provides lightweight tensile strength in spider webs.

- Globular proteins: compact, soluble, functional roles. Examples:

- Enzymes like catalase → catalyze metabolic reactions.

- Hemoglobin → transports oxygen.

- Insulin → regulates blood sugar.

- The contrast between fibrous and globular proteins demonstrates how structure underlies biological roles.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could organize an educational outreach project using 3D models to show how protein folding leads to different properties, raising awareness of protein denaturation in food (e.g., cooking egg white) or health.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Protein structure has direct relevance to medicine and biotechnology. Denaturation explains why fevers can be dangerous. Misfolded proteins are linked to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Structural biology techniques like X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM have enabled drug design by revealing enzyme active sites. In food science, protein denaturation is harnessed to produce cheese, yogurt, and cooked meats.

📌 Protein Properties and Functions

- Solubility, elasticity, and stability all depend on protein structure.

- Denaturation alters these properties, often irreversibly.

- Specificity of enzymes arises from precise active site geometry.

- Structural rigidity of fibrous proteins ensures support and protection.

- Flexibility of globular proteins allows them to act as dynamic regulators and catalysts.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Proteins highlight the role of models in science. Structural diagrams, ribbon models, and molecular simulations each reveal different aspects of protein folding. TOK reflection: How do different visual models influence our perception of something as complex and dynamic as protein structure?