B1.2.2 – PROTEIN STRUCTURE AND PROPERTIES

📌Definition Table

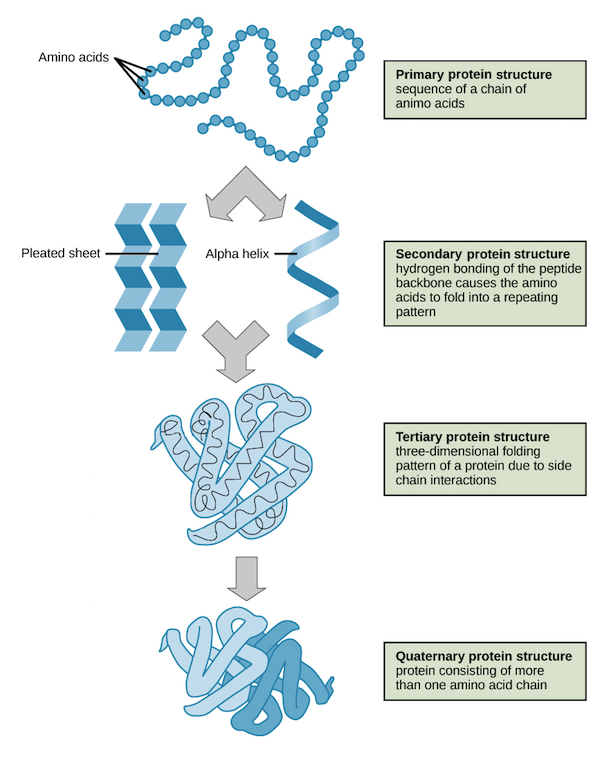

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Primary Structure | The sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. |

| Secondary Structure | Local folding of the polypeptide into α-helices or β-pleated sheets, stabilised by hydrogen bonds. |

| Tertiary Structure | The overall 3D shape of a single polypeptide, determined by R-group interactions. |

| Quaternary Structure | The association of two or more polypeptide chains into a functional protein. |

| Denaturation | Loss of protein’s native structure (and function) due to changes in pH, temperature, or chemicals. |

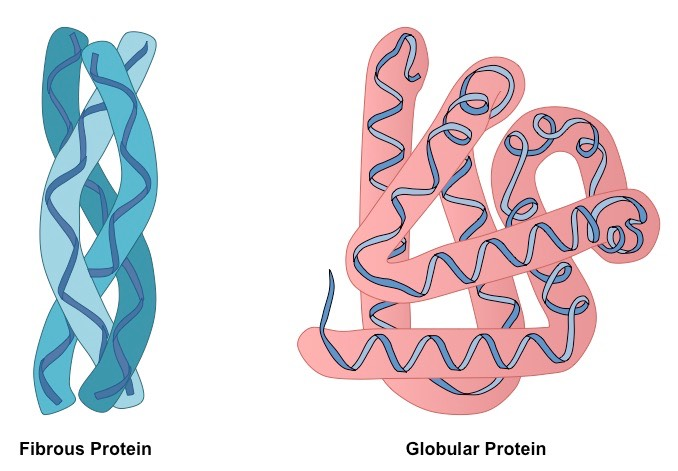

| Globular Protein | Spherical, soluble protein with functional roles (e.g., enzymes). |

| Fibrous Protein | Long, insoluble protein with structural roles (e.g., collagen). |

📌Introduction

Protein structure is hierarchical, progressing from a simple amino acid sequence to complex, functional 3D shapes. These structures are stabilised by various chemical interactions, and even minor changes can alter a protein’s function or cause denaturation. The specific folding of proteins determines their biological role — from catalysis to structural support.

❤️ CAS Link: Create a protein structure model exhibition using materials like clay or 3D-printed parts to illustrate primary through quaternary levels.

📌 Levels of Protein Structure

- Primary: Unique sequence of amino acids; determines higher structures and function.

- Secondary: α-helices and β-pleated sheets formed by hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms.

- Tertiary: 3D folding due to R-group interactions — hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, hydrophobic interactions, disulphide bridges.

- Quaternary: Multiple polypeptides combining (e.g., haemoglobin with four subunits).

- Each level is critical; mutations in the primary sequence can disrupt the entire structure.

- Proteins can be structural (fibrous) or functional (globular).

🧠 Examiner Tip: In long-answer questions, describe at least one type of bond stabilising each structural level for full marks.

📌 Factors Affecting Protein Stability

- Temperature: High heat breaks hydrogen bonds, causing denaturation.

- pH: Changes alter ionic bonds and disrupt folding.

- Chemical Agents: Organic solvents, detergents can disrupt hydrophobic interactions.

- Salt Concentration: High salt can precipitate proteins by disrupting water interactions.

- Some proteins can refold after mild denaturation; others cannot.

- Extremophiles possess proteins stable in extreme conditions.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Enzymes in hot-spring bacteria (e.g., Taq polymerase) are stable at high temperatures and vital for PCR technology.

📌Globular vs. Fibrous Proteins

- Globular: Compact, soluble, dynamic roles (enzymes, hormones, transport). Example: insulin, haemoglobin.

- Fibrous: Long, insoluble, structural roles (collagen in connective tissue, spider silk).

- Differences arise from amino acid sequences and folding patterns.

- Fibrous proteins often have repetitive sequences for strength.

- Globular proteins often have hydrophobic cores and hydrophilic surfaces.

- Structural type relates directly to biological role.

🌐 EE Focus: Investigate thermal stability of different protein types, comparing globular vs fibrous under lab conditions.

📌 Technology in Protein Study

- X-ray crystallography: Determines atomic structure.

- Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM): Visualises proteins without crystallisation.

- NMR spectroscopy: Used for proteins in solution.

- Advances in tech reveal protein folding pathways and dynamics.

- Structural databases store resolved protein models (e.g., Protein Data Bank).

- Computational modelling predicts folding for unstudied proteins.

🔍 TOK Perspective: How do technological advances shape our “certainty” about protein structure, and could future tools prove current models incomplete?