D4.2.3 EQUILIBRIUM AND EVOLUTIONARY CHANGE

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium | Condition where allele and genotype frequencies remain constant in a population. |

| Evolutionary change | Alteration of allele frequencies across generations. |

| Punctuated equilibrium | Long periods of stasis interrupted by rapid evolutionary events. |

| Gradualism | Slow, steady accumulation of evolutionary changes. |

| Stabilising selection | Selection favouring intermediate phenotypes. |

| Directional selection | Selection favouring one extreme phenotype. |

📌Introduction

Populations are not static: they evolve under selective pressures, genetic drift, gene flow, and mutation. However, in the absence of these forces, populations remain in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Evolutionary change can be gradual or punctuated, and selection can stabilise, diversify, or direct populations towards new adaptive peaks. These patterns provide a framework for understanding both microevolutionary changes and macroevolutionary trends in the fossil record

📌 Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

- States that allele frequencies remain constant if no evolutionary forces act.

- Assumptions: large population, random mating, no mutation, no migration, no selection.

- Provides a null model for studying evolution.

- Deviations reveal which evolutionary processes are at work.

- Useful in population genetics, epidemiology, and conservation biology.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Show ability to apply Hardy-Weinberg calculations. Simply defining it without calculation limits marks.

📌 Types of Natural Selection

- Stabilising selection: reduces variation, favours intermediate traits.

- Directional selection: shifts population towards one extreme (e.g., antibiotic resistance).

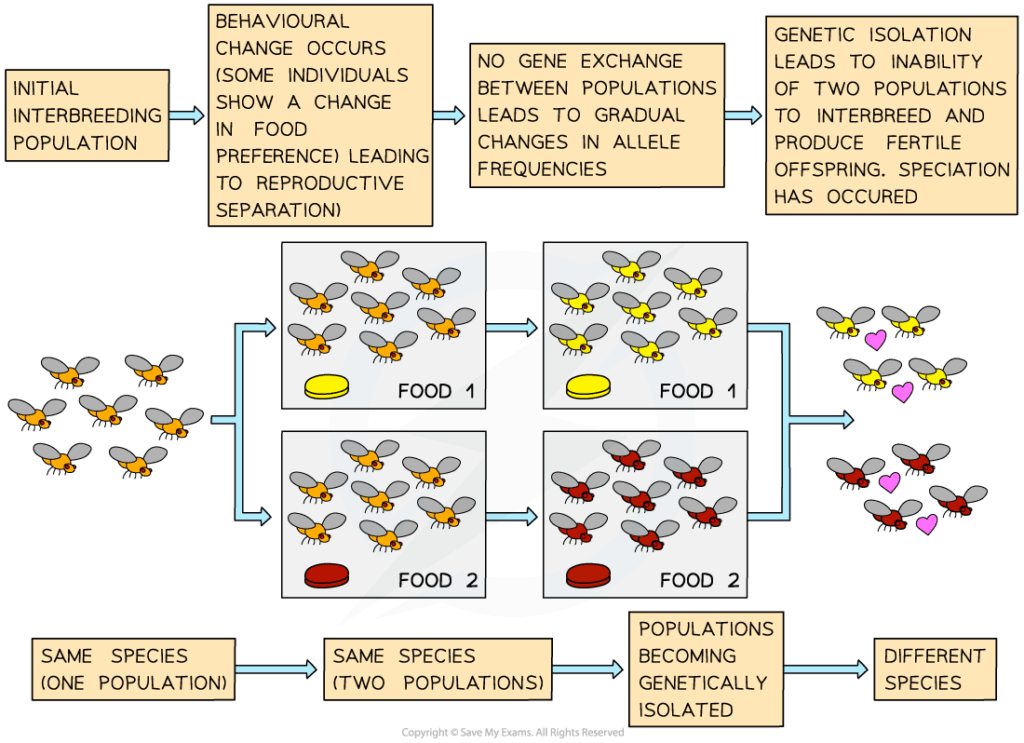

- Disruptive selection: favours both extremes, may lead to speciation.

- Balancing selection maintains multiple alleles (e.g., sickle-cell trait).

- Selection modes shape population equilibrium and change.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could collect data on variation in a measurable trait (e.g., seed size) and test if observed distribution fits stabilising or directional selection.

📌 Gradualism vs Punctuated Equilibrium

- Gradualism: Darwin’s view — small changes accumulate over long time.

- Punctuated equilibrium: Eldredge & Gould — long stasis interrupted by rapid speciation.

- Fossil record supports both: some lineages show stasis, others rapid bursts.

- Environmental shifts (mass extinctions, climate change) often trigger punctuation.

- Together, they reflect multiple evolutionary tempos.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could examine fossil evidence for tempo of evolution, e.g., comparing trilobite stasis vs mammalian radiation post-dinosaur extinction

📌 Microevolution and Macroevolution

- Microevolution: allele frequency shifts within populations.

- Macroevolution: large-scale patterns (speciation, extinction).

- Same processes drive both, but at different scales.

- Links population genetics with paleobiology.

- Demonstrates continuity of evolutionary theory.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could create interactive models showing Hardy-Weinberg dynamics or demonstrate selection types with real-life analogies for school outreach.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Hardy-Weinberg used in medical genetics (tracking allele frequencies in diseases), conservation (managing endangered species), and agriculture (maintaining crop diversity).

📌 Long-Term Evolutionary Dynamics

- Evolution is not linear but shaped by interactions of drift, selection, flow, mutation.

- Extinctions and radiations punctuate long-term patterns.

- Coevolution drives reciprocal adaptations.

- Evolutionary arms races explain rapid trait changes (predator-prey, host-pathogen).

- Stability and change are complementary features of evolution.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Models like Hardy-Weinberg and punctuated equilibrium simplify reality. TOK issue: How far can simplified models capture complex natural processes without distorting understanding?