D4.2.2 SPECIATION AND ISOLATION MECHANISMS

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Speciation | Formation of new species from existing populations. |

| Allopatric speciation | Speciation due to geographic isolation. |

| Sympatric speciation | Speciation within the same geographic area, often due to ecological or behavioural isolation. |

| Prezygotic isolation | Barriers preventing fertilisation (e.g., mating seasons, behavioural differences). |

| Postzygotic isolation | Barriers after fertilisation, such as hybrid sterility. |

| Hybrid | Offspring of two different species or populations, often sterile or less fit. |

📌Introduction

Speciation explains how biodiversity arises. It occurs when populations of the same species become reproductively isolated and diverge genetically. Isolation can be geographic, ecological, behavioural, or genetic. Over time, accumulated differences prevent interbreeding, leading to new species. Understanding speciation mechanisms is critical for explaining adaptive radiation, biodiversity hotspots, and the tree of life

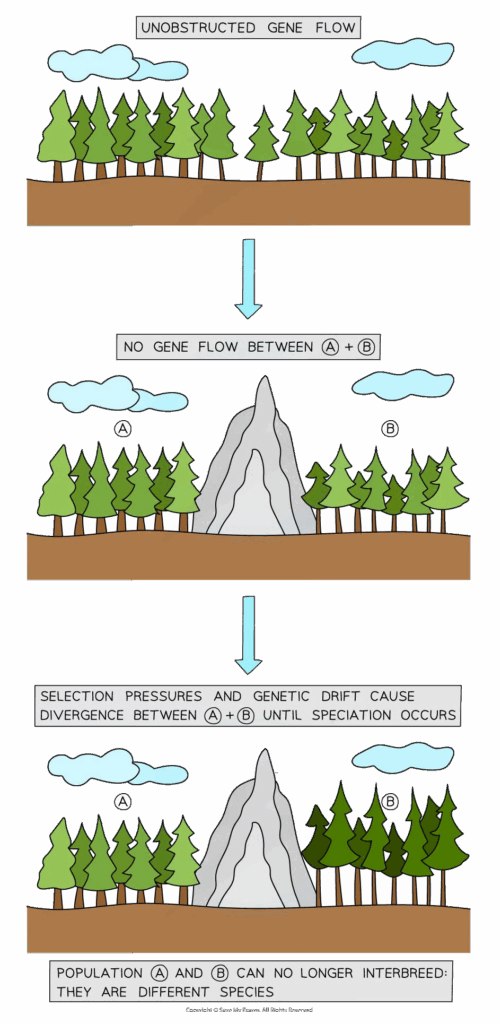

📌 Allopatric Speciation

- Most common form of speciation.

- Geographic isolation (mountains, rivers, islands) separates populations.

- Different environments impose different selective pressures.

- Drift and mutation accumulate independently.

- Reproductive isolation develops after sufficient divergence.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Don’t write “geographic isolation = speciation.” Explain the intermediate steps: isolation → divergence → reproductive isolation → new species.

📌 Sympatric Speciation

- Occurs without physical barriers.

- Often due to ecological niches, e.g., insects specialising on different host plants.

- Behavioural isolation: changes in mating calls, timing, or rituals.

- Polyploidy in plants: sudden speciation through genome duplication.

- Demonstrates that speciation can occur even with gene flow, if selection is strong.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students could model isolation using populations of model organisms (fruit flies, yeast) exposed to different conditions and track divergence.

.📌 Isolation Mechanisms

- Prezygotic barriers: temporal (different mating seasons), behavioural (mating calls), mechanical (incompatible structures).

- Postzygotic barriers: hybrid inviability, hybrid sterility (e.g., mule), reduced hybrid fitness.

- Reinforcement strengthens isolation by favouring avoidance of maladaptive hybridisation.

- Essential in preventing gene flow once divergence has started.

- Maintain distinct species boundaries in sympatric regions.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could compare speciation models (allopatric vs sympatric) using case studies such as cichlid fish, Galápagos finches, or African Rift Valley lakes.

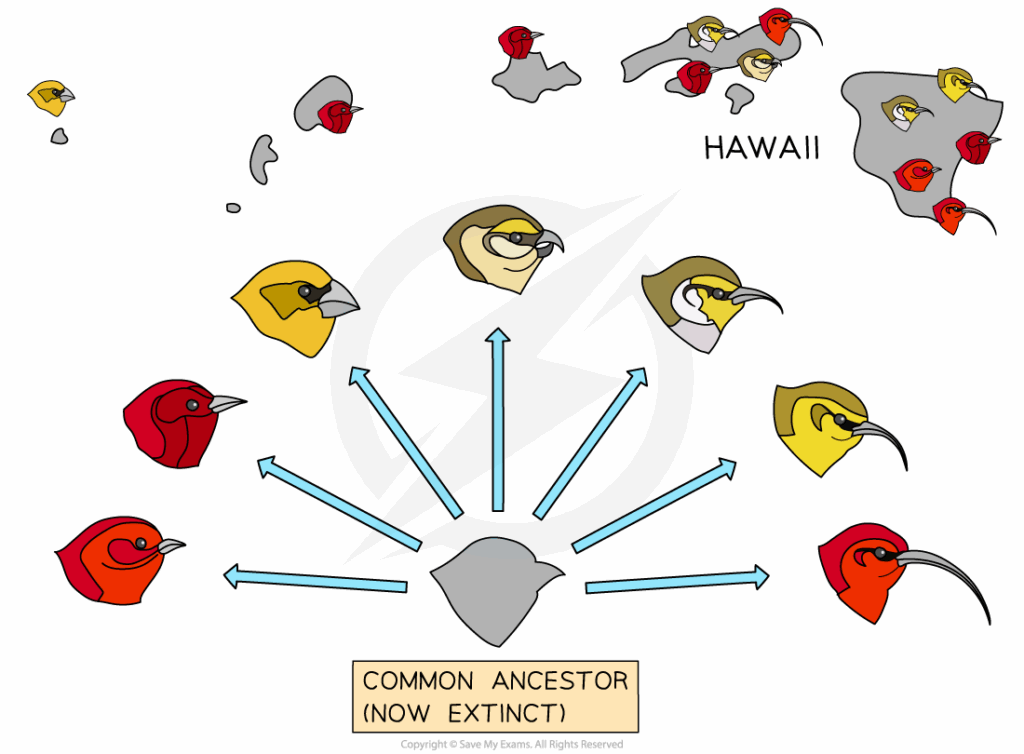

📌 Adaptive Radiation

- Rapid speciation when organisms colonise new environments.

- Classic examples: Darwin’s finches, Hawaiian honeycreepers.

- Driven by ecological opportunities and niche differentiation.

- Produces high biodiversity in island ecosystems.

- Demonstrates power of speciation in generating diversity.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design posters or presentations on local endemic species and their speciation histories, raising awareness of biodiversity conservation.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Speciation studies inform conservation strategies, especially for endangered species management and biodiversity preservation. They also guide agriculture (e.g., polyploid crops).

📌 Patterns of Speciation

- Gradualism: slow, continuous accumulation of changes.

- Punctuated equilibrium: long stability interrupted by rapid bursts of change.

- Both models supported by fossil evidence.

- Different taxa may follow different patterns.

- Together, they illustrate flexibility of evolutionary tempo.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Species boundaries are not always clear-cut. TOK issue: How do scientists deal with concepts (like “species”) that have fuzzy, debated definitions?