D1.3.2 EFFECTS OF MUTATIONS ON PROTEINS AND PHENOTYPES

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Phenotype | Observable traits or characteristics of an organism resulting from genotype and environment. |

| Missense mutation | A base substitution that changes one amino acid in the polypeptide chain. |

| Nonsense mutation | A mutation that introduces a premature stop codon, producing truncated proteins. |

| Frameshift mutation | Mutation caused by insertion or deletion of bases, altering the reading frame. |

| Loss-of-function mutation | Mutation that reduces or abolishes a protein’s activity. |

| Gain-of-function mutation | Mutation that enhances or introduces a new protein function. |

📌Introduction

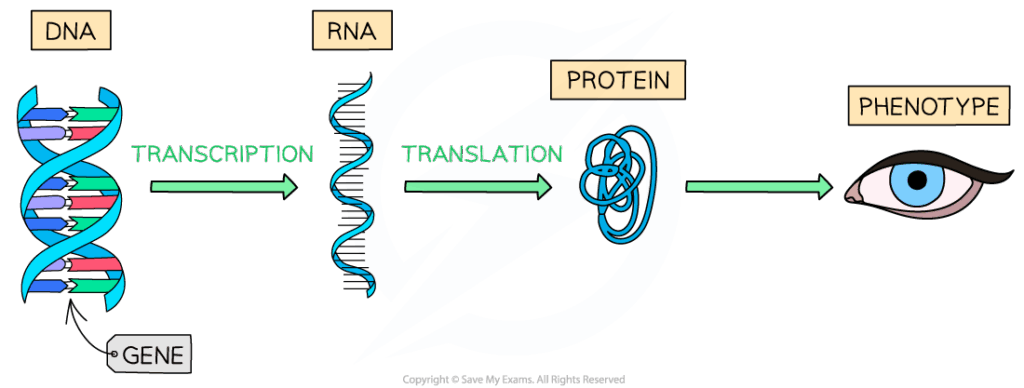

Mutations affect proteins by altering amino acid sequences, folding, or regulation, which in turn changes phenotypes. While some mutations are silent with no observable effects, others disrupt critical functions and cause disease. Mutations can also create beneficial traits that drive adaptation. Studying these outcomes reveals the intricate link between genotype, protein function, and phenotype

📌 Impact on Protein Structure and Function

- Missense mutations can alter protein shape or stability (e.g., sickle-cell hemoglobin).

- Nonsense mutations truncate proteins, usually rendering them non-functional.

- Frameshifts completely disrupt amino acid sequences, often highly deleterious.

- Mutations in active sites or binding regions severely impair enzyme activity.

- Some mutations alter folding pathways, leading to aggregation and toxicity.

🧠 Examiner Tip: When linking mutations to proteins, always explain how amino acid changes affect structure (primary → tertiary) and function.

📌 Impact on Phenotypes

- Single-gene disorders: e.g., cystic fibrosis from CFTR gene mutations.

- Metabolic defects: enzyme deficiencies causing conditions like phenylketonuria.

- Morphological changes: mutations affecting developmental genes (HOX) altering body structure.

- Resistance traits: mutations conferring antibiotic resistance in bacteria or pesticide resistance in insects.

- Neutral effects: silent mutations or mutations in non-coding DNA with no observable phenotype.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: A lab investigation could track phenotypic changes in bacterial colonies under antibiotic stress, showing mutation-driven resistance.

📌 Beneficial vs. Harmful Effects

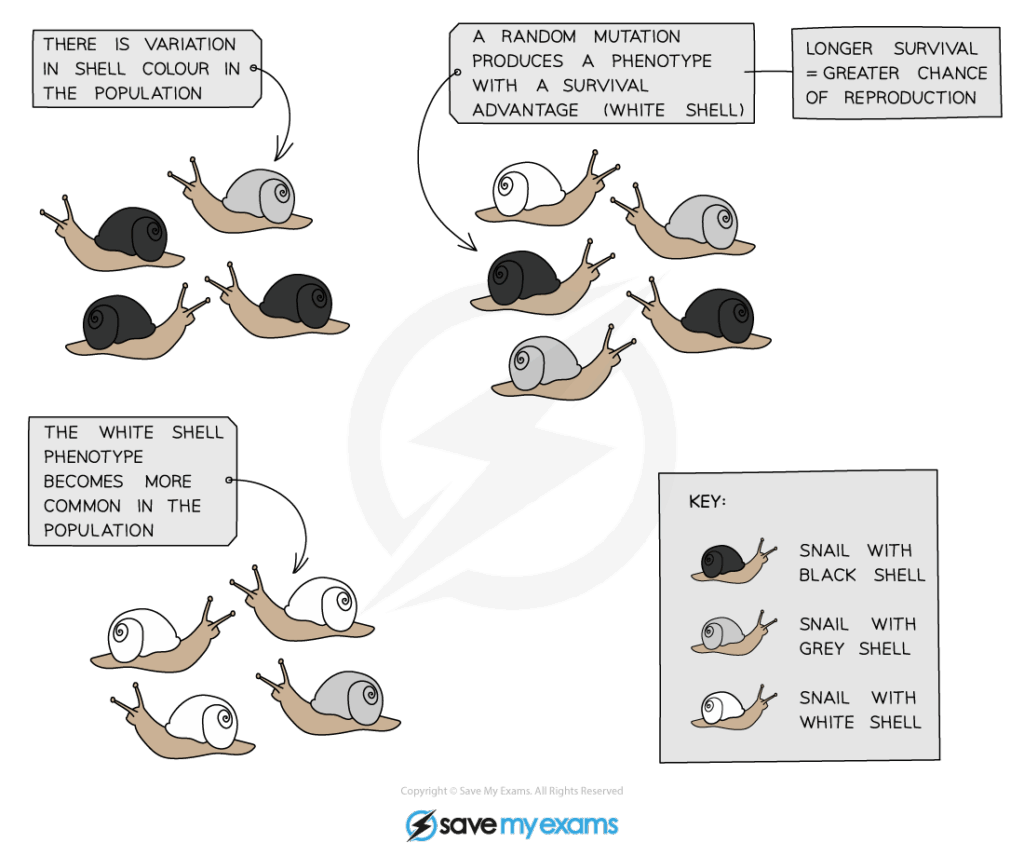

- Beneficial mutations increase survival or reproduction (e.g., lactase persistence in adults).

- Harmful mutations cause disease or lower fitness.

- Neutral mutations accumulate as genetic variation without obvious effects.

- The same mutation may be harmful in one environment but beneficial in another (e.g., sickle-cell trait).

- Evolution depends on the balance of these effects in populations.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could explore how single-gene mutations manifest differently across populations, such as the protective effect of sickle-cell trait in malaria regions.

📌 Molecular Basis of Mutation Effects

- Loss-of-function mutations disrupt normal gene activity; often recessive.

- Gain-of-function mutations create hyperactive proteins; often dominant.

- Mutations in regulatory regions alter gene expression levels.

- Splicing mutations can exclude essential exons, producing dysfunctional proteins.

- Expanded trinucleotide repeats (e.g., Huntington’s disease) cause protein aggregation.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design community outreach activities on genetic screening, raising awareness of how early detection of mutations can inform health choices.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Mutations underlie thousands of human genetic diseases, from sickle-cell anemia and Duchenne muscular dystrophy to cancers caused by oncogene and tumor suppressor mutations. Beneficial mutations, such as CCR5-Δ32 conferring HIV resistance, highlight medical potential. In agriculture, mutations shape crop and livestock breeding, while in microbes, mutation-driven resistance challenges public health.

📌 Mutations and Evolutionary Significance

- Mutations provide the raw material for adaptation and natural selection.

- Evolutionary novelties often trace back to mutations in developmental regulatory genes.

- Comparative genomics identifies conserved vs. mutated regions across species.

- Mutation rates vary across organisms, shaping evolutionary trajectories.

- Human variation and personalized medicine rely on identifying specific mutations.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Classifying mutations as “harmful” or “beneficial” depends on context and human values. TOK reflection: How do cultural, medical, or environmental perspectives influence our judgment of genetic change?