C4.1.3 ECOLOGICAL SUCCESSION AND STABILITY

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Succession | The gradual change in community composition over time. |

| Primary succession | Succession starting on bare rock or newly formed surfaces with no soil. |

| Secondary succession | Succession in disturbed areas where soil remains (e.g., after fire). |

| Pioneer species | The first species to colonise new or disturbed environments. |

| Climax community | A stable, self-sustaining community at the end of succession. |

| Resilience | The ability of an ecosystem to recover after disturbance. |

📌Introduction

Ecological succession describes how communities change over time, driven by species colonisation, competition, and modification of the environment. Succession increases biodiversity and complexity until a stable climax community is established. However, disturbances such as fire, storms, or human activity can reset succession. Ecosystem stability depends on resilience — the capacity to recover after such events

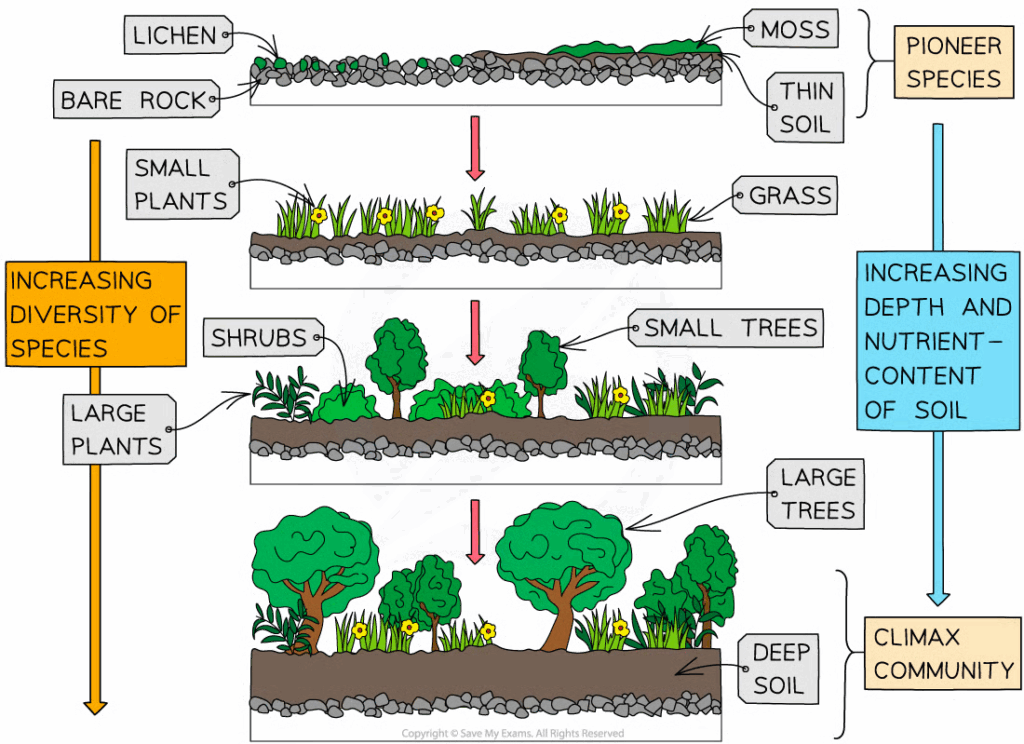

📌 Primary Succession

- Begins on bare rock (volcanic islands, retreating glaciers).

- Pioneer species (lichens, mosses) colonise first, breaking rock into soil.

- Soil formation allows grasses, shrubs, and eventually trees to grow.

- Increases organic matter, nutrient cycling, and habitat complexity.

- Takes hundreds to thousands of years to reach a climax community.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Distinguish clearly between primary and secondary succession — many students mix them up.

📌 Secondary Succession

- Occurs after disturbances that remove communities but leave soil intact.

- Faster than primary succession because soil and seeds remain.

- Common after forest fires, floods, or abandoned farmland.

- Communities rebuild through stages: weeds → grasses → shrubs → trees.

- Biodiversity recovers more quickly than in primary succession.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Students can monitor succession in school grounds (e.g., abandoned plots) over months, recording species diversity.

📌 Climax Communities and Stability

- Climax community is the endpoint of succession: stable, high biodiversity.

- Composition depends on climate (e.g., tropical rainforest vs desert).

- Dynamic equilibrium: communities remain stable but not static.

- Disturbances (storms, fires) may shift communities into new stable states.

- Human activity (logging, farming) often prevents climax formation.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could compare primary vs secondary succession in local ecosystems, using biodiversity indices to track recovery.

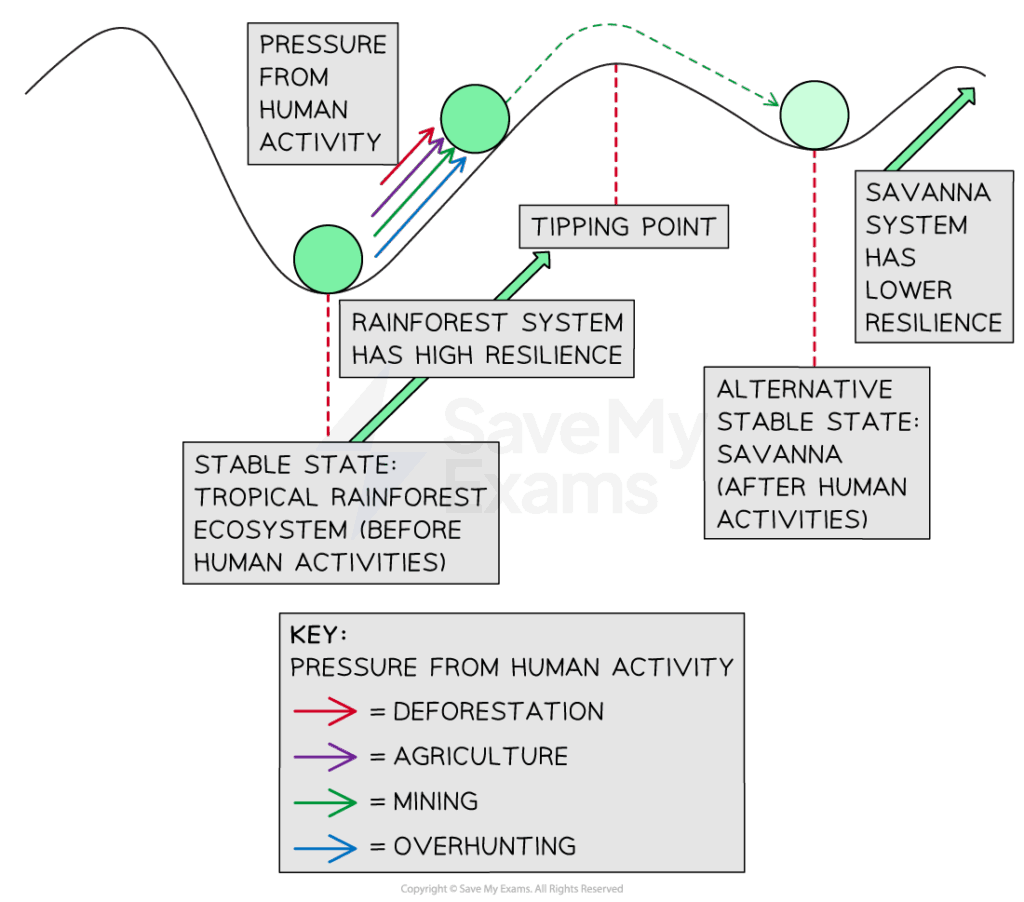

📌 Resilience and Disturbance

- Ecosystems vary in resilience — ability to bounce back after disturbance.

- High diversity often increases resilience by providing functional redundancy.

- Keystone species contribute to recovery capacity.

- Disturbance regimes (frequency, intensity) determine community pathways.

- Low resilience ecosystems risk collapse under repeated stress.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could support local ecological restoration projects, such as planting native species in degraded areas.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Succession and resilience are central to habitat restoration, rewilding, and conservation strategies. Climate change increases disturbance frequency, testing ecosystem stability.

📌 Human Impacts on Succession

- Agriculture and urbanisation halt natural succession.

- Invasive species alter successional pathways by outcompeting natives.

- Fire suppression changes natural disturbance regimes, reducing biodiversity.

- Restoration ecology seeks to guide succession towards desired outcomes.

- Humans both hinder and manage succession processes.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Succession is often depicted as a linear pathway to climax. TOK issue: Do such models ignore the unpredictability and multiple possible outcomes of real ecosystems?