C1.1.1 PROPERTIES AND STRUCTURE OF ENZYMES

📌Definition Table

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Enzyme | A biological catalyst, usually a protein, that speeds up biochemical reactions without being consumed. |

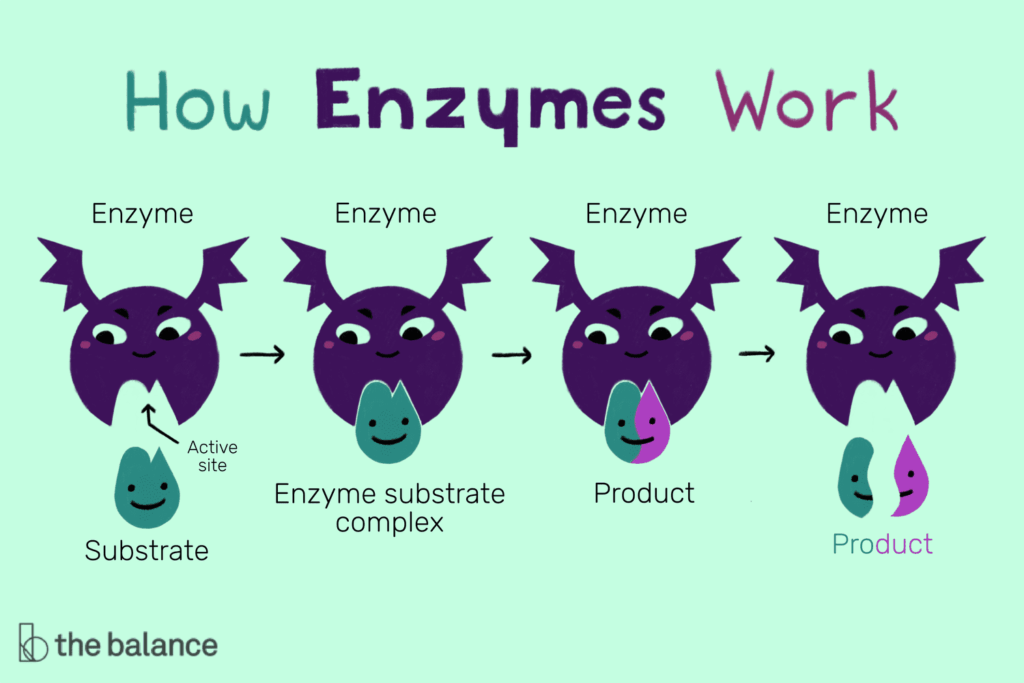

| Active site | Specific region on an enzyme where the substrate binds and catalysis occurs. |

| Substrate | The reactant molecule upon which an enzyme acts. |

| Specificity | The ability of an enzyme to act on a particular substrate due to complementary shape and chemical properties. |

| Cofactor | A non-protein component (metal ion or organic molecule) required for enzyme activity. |

| Apoenzyme | Protein portion of an enzyme without its cofactor. |

| Holoenzyme | Complete, active enzyme consisting of apoenzyme plus cofactor. |

📌Introduction

Enzymes are essential for life because they accelerate chemical reactions that would otherwise occur too slowly to sustain metabolism. They provide specificity, efficiency, and regulation, enabling organisms to maintain homeostasis. Most enzymes are globular proteins whose unique 3D conformation determines their catalytic function. Enzymes lower activation energy by stabilizing the transition state, allowing reactions to proceed rapidly under physiological conditions of temperature and pH.

📌 Structure of Enzymes

- Enzymes are primarily globular proteins with a unique tertiary or quaternary structure.

- Their active site is a small, highly specific region formed by amino acid residues.

- Specificity arises from complementary shapes, charges, and hydrophobic interactions between enzyme and substrate.

- Cofactors expand enzyme functionality:

- Metal ions (Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Fe²⁺) assist in catalysis.

- Coenzymes (organic molecules like NAD⁺, FAD, CoA) act as carriers of electrons or chemical groups.

- Enzymes exhibit induced fit: binding of the substrate induces slight conformational changes, optimizing interaction and catalysis.

- The polypeptide folding and stability are maintained by hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, disulfide bridges, and hydrophobic interactions.

🧠 Examiner Tip: Always emphasize that enzymes lower activation energy but do not change the overall free energy (ΔG) of the reaction. This is a frequent exam misconception.

📌 Properties of Enzymes

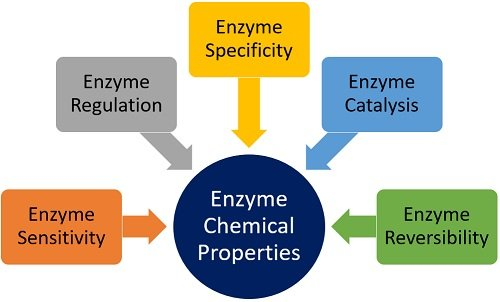

- Catalytic efficiency: Enzymes increase reaction rates by factors of up to 10⁶–10¹².

- Specificity: Each enzyme acts only on one or a few related substrates (e.g., sucrase hydrolyzes sucrose but not lactose).

- Reusability: Enzymes are not consumed; a single enzyme molecule can catalyze many reactions.

- Mild conditions: Enzymes operate at physiological temperatures and pH, unlike harsh industrial catalysts.

- Saturation kinetics: Reaction rate increases with substrate concentration until all active sites are occupied.

- Regulation: Enzymes can be activated or inhibited by molecules, allowing fine-tuned metabolic control.

🧬 IA Tips & Guidance: Enzyme catalysis is a classic IA theme. Investigations could test the effect of temperature, pH, or inhibitors on catalase activity (measured by O₂ release) or amylase (starch breakdown). Always justify how chosen conditions affect enzyme structure and activity.

📌 Examples of Enzymes and Cofactors

- DNA polymerase: requires Mg²⁺ for nucleotide addition.

- Carbonic anhydrase: Zn²⁺ at its active site catalyzes CO₂ hydration.

- Dehydrogenases: use NAD⁺/FAD as coenzymes to transfer electrons in respiration.

- Hemoglobin (not an enzyme but an example of cofactor use): requires Fe²⁺ in heme group.

🌐 EE Focus: An EE could explore comparative enzyme structure using bioinformatics — e.g., structural similarities among hydrolases, or evolution of active sites in oxidoreductases. Another option is studying the effect of cofactors on enzyme kinetics experimentally.

📌 Enzymes in Cells

- Enzymes are localized in specific organelles to maintain efficiency:

- Mitochondria → Krebs cycle enzymes.

- Chloroplasts → photosynthetic enzymes.

- Lysosomes → hydrolytic enzymes at acidic pH.

- Compartmentalization prevents interference between pathways and creates optimal microenvironments.

- Multienzyme complexes (e.g., pyruvate dehydrogenase) channel substrates directly between enzymes, increasing efficiency.

❤️ CAS Link: Students could design community activities demonstrating enzyme presence in everyday life (e.g., pineapple juice breaking down gelatin, detergent enzymes digesting stains), linking biology to food science and sustainability.

🌍 Real-World Connection: Enzymes are widely used in biotechnology and medicine. Industrial applications include amylases in brewing, proteases in detergents, and lipases in food processing. Clinically, enzymes serve as biomarkers (elevated amylase in pancreatitis), therapeutic agents (streptokinase dissolving clots), and drug targets (HIV protease inhibitors). Enzyme deficiencies (e.g., lactase deficiency → lactose intolerance) illustrate their importance for health.

📌 Stability and Denaturation

- Enzyme function depends on the stability of their 3D conformation.

- High temperatures or extreme pH disrupt hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions, causing denaturation.

- Denatured enzymes lose active site shape → no substrate binding or catalysis.

- This property underpins food preservation (pasteurization) and sterilization techniques.

🔍 TOK Perspective: Much of enzyme knowledge comes from indirect observation (e.g., reaction rates, crystallography). TOK reflection: How reliable are models built from indirect experimental evidence, and to what extent do they represent reality?